FIONA O’CONNOR and MARIA DUARTE review State of Statelessness, Rental Family, 28 Years Later: The Bone Temple, and The Rip

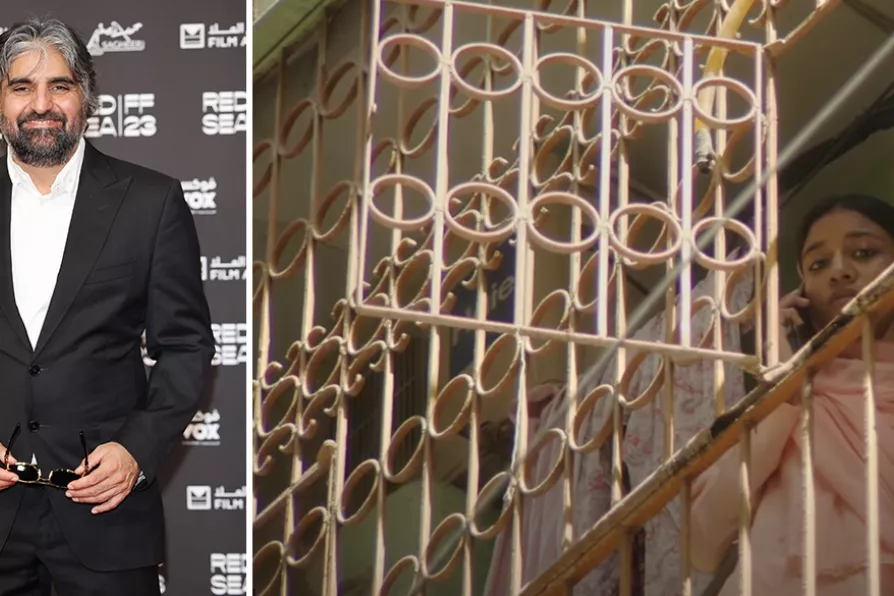

Kaleem Aftab, director of Red Sea Film Festival; a still from the overall winner, In Flames, directed by Zarrar Kahn, an intimate Pakistani-Canadian horror film about a woman, played by Ramesha Nawal, caught in the cage of patriarchal violence

[Courtesy of XYZ films]

Kaleem Aftab, director of Red Sea Film Festival; a still from the overall winner, In Flames, directed by Zarrar Kahn, an intimate Pakistani-Canadian horror film about a woman, played by Ramesha Nawal, caught in the cage of patriarchal violence

[Courtesy of XYZ films]

IN a country where cinema had been banned for 35 years, the Red Sea Film Festival has just concluded its third edition. Staged in Jeddah, the festival has rapidly expanded its scope, not doubling but quadrupling its relevance in Saudi Arabia, the Middle East, even in the wider world.

Artistic director Kaleem Aftab has witnessed the evolution of this festival since the first edition. A journalist and film critic with a huge knowledge of Arabic film and a wealth of experience gained from travelling to festivals across the world, Kaleem was initially brought on as a consultant but subsequently invited to become the artistic director.

“I grew up in London. I’m a Muslim, so I understand what it’s like to have different cultures. My parents were Pakistani immigrants; when I grew up, there was a lot of racism in the ’70s and ’80s. I was always code-switching. I can see the necessity of doing that in the Arab world, with cinema, in particular, especially as over the last 20 years Arab cinema has changed and developed. Saudi is a place where cinema was once banned; it has been fascinating working here.”

Do you think about the audience when you are programming?

RITA DI SANTO gives us a first look at some extraordinary new films that examine outsiders, migrants, belonging and social abuse

RITA DI SANTO speaks to the exiled Ukrainian director Sergei Loznitsa about Two Prosecutors, his chilling study of the Stalinist purges

RITA DI SANTO surveys the smorgasbord of films on offer at this year’s festival