GORDON PARSONS is bowled over by a skilfully stripped down and powerfully relevant production of Hamlet

Split seams

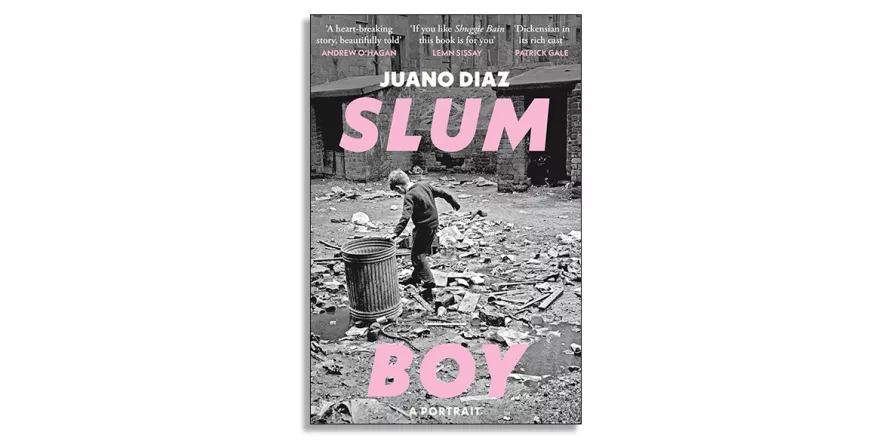

MATTHEW HAWKINS savours the memoir of growing up in the slums of Glasgow in the 1970s and '80s

Slum Boy: a portrait

Juano Diaz

Brazen, £20

INSTEAD of struggling to write sentences with lots of adjectives as his teacher has decreed, a tiny child with scant schooling plays with a pair of craft scissors.

He cuts a long slit up the outside of his trousers and is absorbed by the miracle of his revealed leg. Happening upon on this, his teacher is horrified and shouty. She demands to know why he has done this bit of sartorial damage and she threatens him with punishment if he cannot explain himself. His expression of bafflement seems like the right way of joining in.

More from this author

MATTHEW HAWKINS pays tribute to the performance artist and costumier, Leigh Bowery

MATTHEW HAWKINS is drawn into the everyday lives of women and girls in Muslim communities in southern India

MATTHEW HAWKINS admires a writer with the gumption and wit to extend a transformative experience of autism to the reader

MATTHEW HAWKINS applauds two evocative new productions that have premiered at the Edinburgh Fringe before touring nationwide

Similar stories

MATTHEW HAWKINS admires a writer with the gumption and wit to extend a transformative experience of autism to the reader

ANGUS REID asks where Scotland’s finest band goes next now that it has used its first three albums to come out as gay

The Star's critic MARIA DUARTE reviews Made in England: The Films of Powell and Pressburger; Our Mothers; Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes; and The Almond and the Seahorse

MATTHEW HAWKINS treads warily through the symphonic history of a subject that our present understanding can only obscure