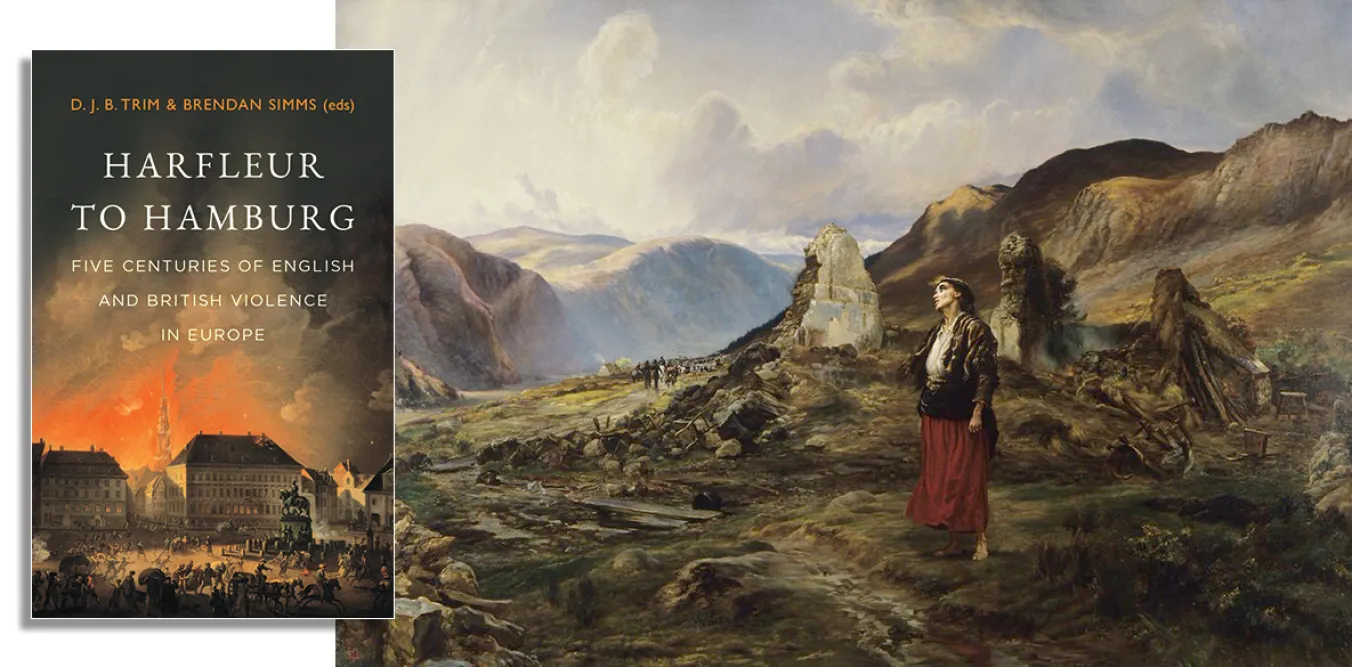

Harfleur to Hamburg: five centuries of English and British violence in Europe

edited by DJB Trim and Brendan Simms, Hurst, £38.80

THIS splendid book takes 11 case studies of English and British violence in Europe: Henry V’s wars in France, Henry VIII’s wars, the atrocities in the reign of Elizabeth I, the subjection of early modern Ireland, the violence in Scotland after the 1746 Battle of Culloden, the bombardment of Copenhagen in 1807, the violence against civilians during the Peninsular War of 1807-14, the Baltic campaign of the Crimean War, 1854-56, the blockade in the first world war, the attack on the French fleet at Mers-El-Kebir in 1940, and the 1943 bombing of Hamburg and other German cities.

The editors sum up: “England and then Great Britain inflicted extreme violence on its European neighbours, even when still using the rhetoric of neighbourliness and friendship.”