JOHN GREEN, MARIA DUARTE and ANGUS REID review Fukushima: A Nuclear Nightmare, Man on the Run, If I Had Legs I’d Kick You, and Cold Storage

This double-dealing, false-speaking time

WILL PODMORE recommends a readable introduction to the life of Byron, in his own words

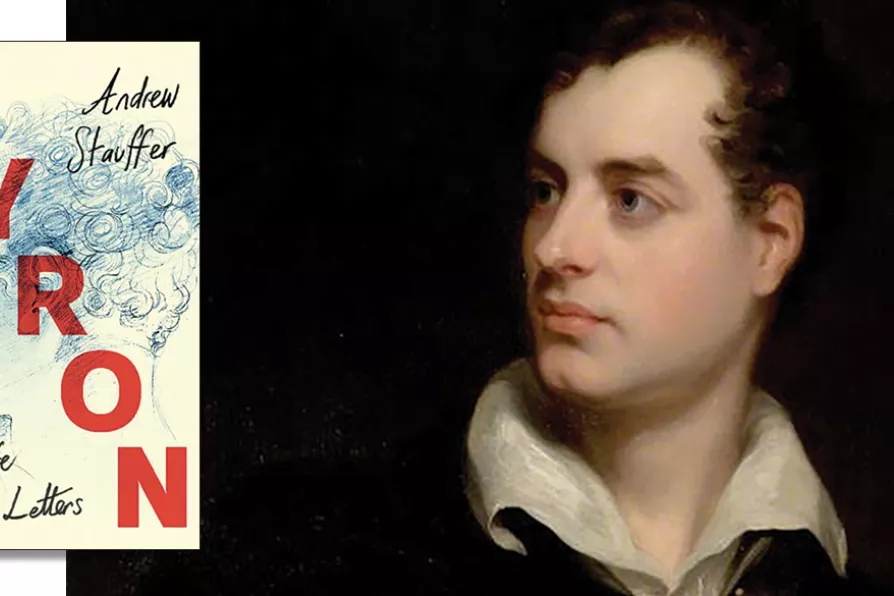

Byron by Thomas Phillips, 1813

[Public Domain]

Byron by Thomas Phillips, 1813

[Public Domain]

Byron: A Life in Ten Letters

Andrew Stauffer

Cambridge University Press, £25

THIS is a fine introduction to the great poet, which should stimulate the reader to read or reread the poems. Its author, Professor Andrew Stauffer, is chair of the Department of English at the University of Virginia, and president of the Byron Society of America.

It is not a full biography; for this, one should turn to Leslie Marchand’s Byron: a biography or to Fiona MacCarthy’s more recent Byron: life and legend.

Similar stories

MARY CONWAY is disappointed by a play that presents Shelley as polite and conventional man who lives a chocolate box, cottagey life

These are vivid accounts of people’s experiences of far-right violence along with documentation of popular resistance, says MARJORIE MAYO

A recognition that individually we are powerless both politically and socially is essential, writes GORDON PARSONS

PATRICK JONES recommends a vital anthology from Afghan and Iranian poets where the political and personal fuse into witness-bearing and manifesto-making