Pity The Swagman. The Australian Odyssey of a Victorian Diarist

Bethan Phillips, Y Olfa, £16.99

ON a cold December evening in 1868 Joseph Jenkins, a Welsh tenant farmer aged 50 had had enough. He abandoned his wife and eight surviving children and trudged overland to Tregaron Station, thence to Aberystwyth, on to Liverpool and bought a one-way ticket to Australia.

The proximate cause of this sudden departure wasn’t economic, and he wasn’t leaving to remit funds back home. Joseph was good at farming. Despite the Welsh winters his cattle were prize winners. He was a renowned poet, much in demand for verses at weddings. He was instrumental in getting rail services into Cardiganshire. A faithful agent of the aristocracy he canvassed in elections for the preferred landlord class.

But he wasn’t an easy man to live with in and May 1868 his family severely beat him up.

Only his version of events survives but he reports a two-hour assault including his son and wife attempting to strangle him. He was treated for broken ribs and severe bruising, some of which he related in verse.

It’s not clear when he decided to quit the house, but the following months brought more misfortune including failed electoral canvassing and a court case. Clearly subject to morose pondering, throughout his life he felt fate was against him.

Emigration to the colonies and its new frontiers was a pull factor for many impoverished Europeans. Most went to escape poverty. For Jenkins, Australia was an escape from himself.

We know all this because Jenkins kept a diary, which remained in the attic of his daughter until the 1970s. His grandson, Dr William Evans had become a renowned cardiologist and published excerpts from the 25 Australian diaries in 1975.

But there were a further 33 Welsh diaries, notebooks, keepsakes and further material kept by the family including a diary by Jenkins’s daughter, all of which provide material for Bethan Phillips’s work which is republished this year.

The work is unusual as most diarists in the British tradition were from upper social strata, one thinks of Samuel Pepys, a naval administrator and MP or Francis Kilvert, a clergyman, (and contemporary of Jenkins). But Jenkins had a rudimentary education and worked on the land.

His diary was initially conceived as a means of self-improvement, in particular in his English skills. As such it contains first hand accounts of rural life in Cardiganshire, many of his verses, and accounts of his voyage to, and subsequent life the Australian colonies.

Australia was tough on Jenkins. From being the boss of his Welsh farm he arrived with only his labour to sell, and became the “swag man” of the title.

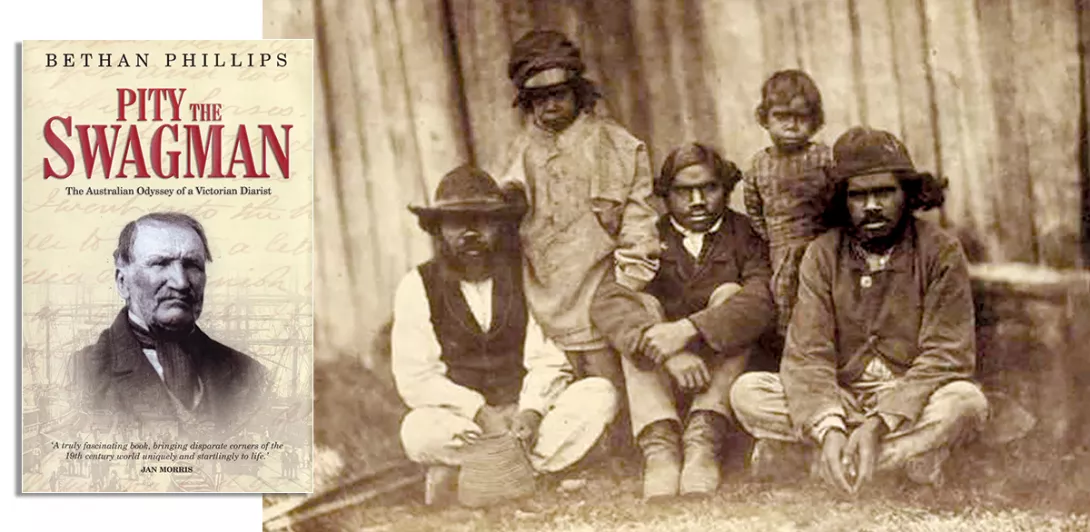

These transient labourers walked from farm to farm offering their work, the swag was a bundle of belongings and something to sleep on, often times this would out in the open. From threshing grain to gold prospecting, ploughing virgin soil to shearing sheep, the life of an agricultural labourer meant 17-hour days in punishing conditions, not least the daytime heat and seasonal floods. Age meant nothing and Jenkins was grafting well into his late 70s.

Welsh communities flourished in parts of Australia, Jenkins was able to win prizes for his poetry at various Eisteddfods. But he was a man of contradiction. He showed unusual sympathy for people in straightened circumstances such as the Aborigines, or the Chinese immigrants, and indeed the swag-men.

Equally he was an admirer of Queen Victoria, but totally against women’s enfranchisement. In Wales he took to drink with some gusto; in Australia he signed temperance pledges.

After 26 years he returned to Wales. The bitterness with which he left remained, and his return was difficult for himself and his family. Many of his children had died, some he last saw as babies.

The great value in Jenkin’s diaries is their contemporary descriptions of life in two continents including that of rural work in Wales and Australia. Nowadays a fountain and plaque sits to recognise his diaries as his own monument at Maldon railway station, which he left in 1894.

Bethan Phillips expertly guides us through a rich source of information which is now part of the school curriculum in Australia.