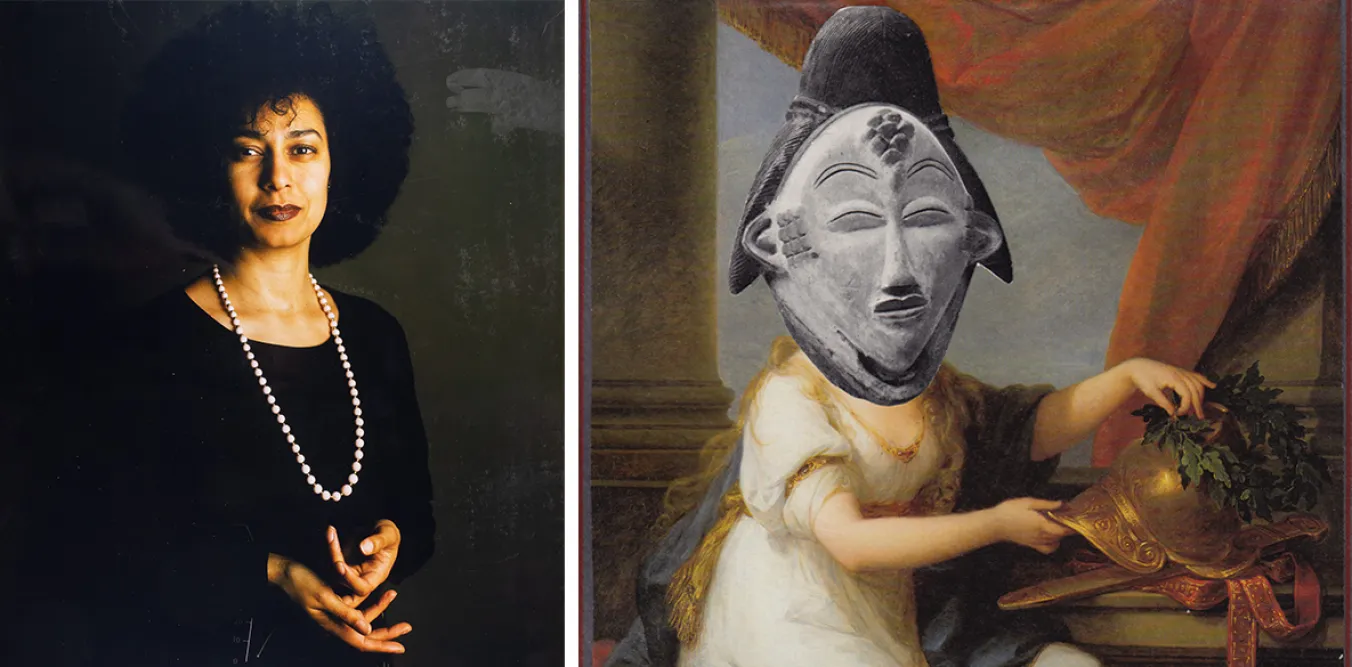

AKINWANDE OLUWOLE SOYINKA, the legendary African author and activist, is proof of what words and acts can achieve in the struggle for justice and human rights. Soyinka, aged 90, embodies unrelenting activism and literary excellence.

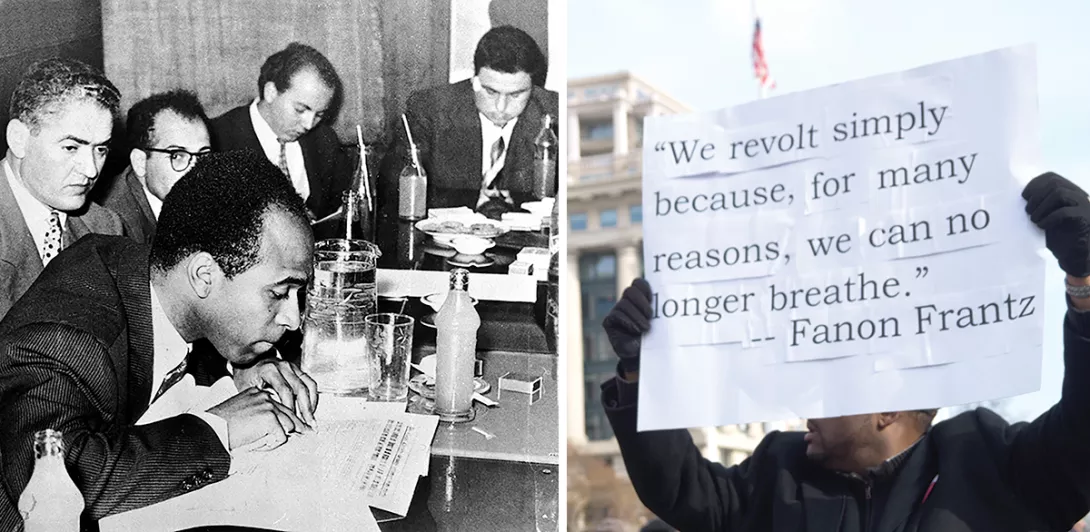

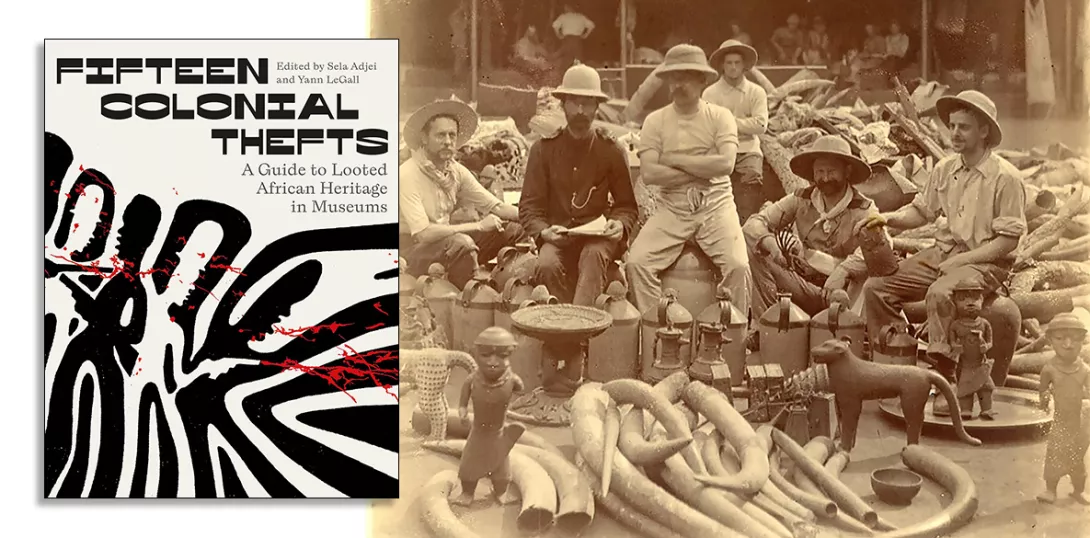

The importance of Soyinka’s work lies in demonstrating the powerful role of the arts and artists in society. He has shown that literature and artistic expression can be formidable tools for challenging oppression, advocating for justice and inspiring social change.

From his early plays and poems to his recent essays and speeches, Soyinka has consistently addressed political corruption, social injustice and human rights abuses — often at great personal risk. His works galvanise readers and audiences to think critically and act courageously.