ALAN McGUIRE welcomes the complete poems of Seamus Heaney for the unmistakeable memory of colonialism that they carry

Ideas that resonate

The Wretched of the Earth has been translated into South Africa’s Zulu language. Its translator MAKHOSAZANA XABA explains why Frantz Fanon’s revolutionary book still matters and why is it important that books like this be available in isiZulu

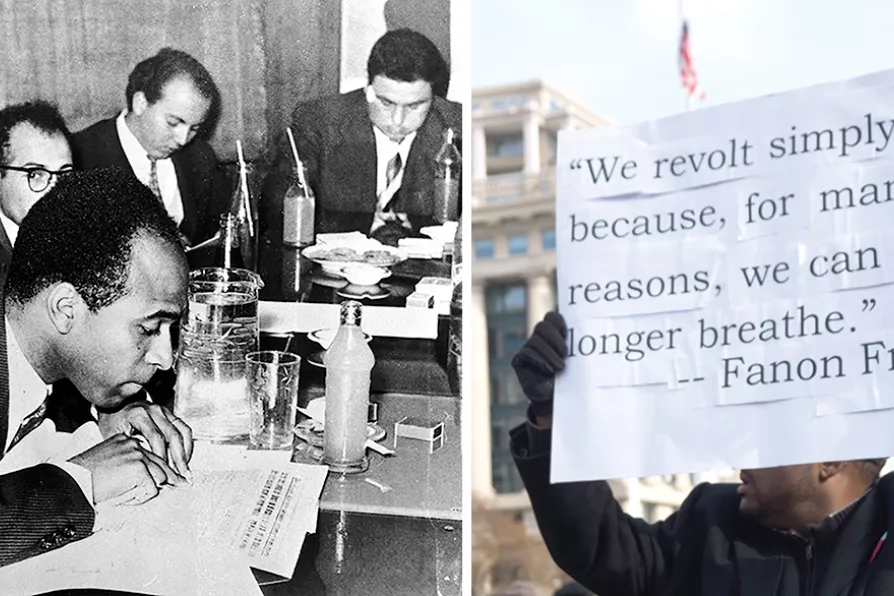

CONTINUING RELEVANCE: (Left) Frantz Fanon at a press conference during a writers' conference in Tunis, 1959; (right) Justice for All March Washington DC in 2014

[(L to R) Public domain/CC - fuseboxradio/CC]

CONTINUING RELEVANCE: (Left) Frantz Fanon at a press conference during a writers' conference in Tunis, 1959; (right) Justice for All March Washington DC in 2014

[(L to R) Public domain/CC - fuseboxradio/CC]

ALTHOUGH newspapers in isiZulu, a Southern Bantu language, have existed since the mid-1800s, only Ilanga lase Natal, founded in 1903, has survived. But the readership for isiZulu literature is massive.

IsiZulu is the majority language in South Africa; 23 per cent of the population speaks it as their first language.

Similar stories

HEIDI NORMAN welcomes a new history of the Aboriginal resistance to white settlers in New South Wales

ALASTAIR BONNETT reports on the paradoxes of populist attitudes towards protection of the natural world

Following his death a month ago, DENNIS WALDER assesses the achievement of the playwright who developed his work in the townships

ANA ISABEL NUNES points to the empowering legacy of Augusto Boal’s Theatre Of The Oppressed