GORDON PARSONS is bowled over by a skilfully stripped down and powerfully relevant production of Hamlet

New seeds of protest

BEN LUNN reports from a new music festival in New York, and singles out a breathtaking composition that protests directly against femicide in Mexico

STAYING in New York in the midst of a heatwave, where the smell of tarmac and weed shaped the air, isn’t necessarily my ideal set-up for a conference and music festival; but fate had other ideas.

More from this author

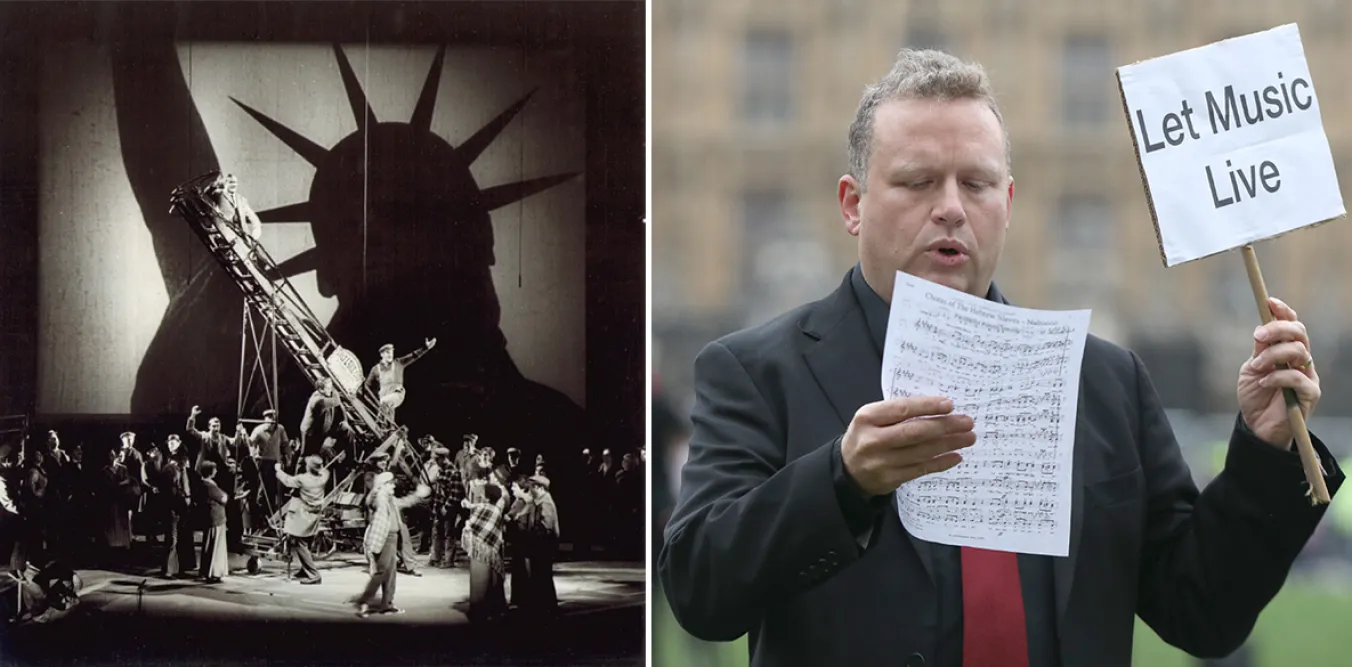

BEN LUNN draws attention to the way cultural expressions of solidarity with Palestinians in the UK are being censored by Israeli-sponsored lawfare

The centenary of his birth is a chance to assess the remarkable combination of Marxism, activism and modernism in the works of Luigi Nono

As the debate around voluntary euthanasia returns, we now have some seriously disturbing evidence from those places where it has become recently legalised to convince us that Britain is not ready, argues BEN LUNN

BEN LUNN argues that opera has long been an arena of radical ideas and music and shouldn't be an art form lost to the wealthy

Similar stories

GEORGE FOGARTY introduces himself to the healing power of traditional Indian music

CHRIS SEARLE interviews veteran pianist VERYAN WESTON

BEN LUNN speaks to Mexican composer Jimena Maldonado about her work for vibraphone and voice, Repeat Their Names

SIMON DUFF revels in a performance by up and coming concert pianist Aidan Chan