ANDY HEDGECOCK is enthralled by a collection of South Korean ghost stories where human behaviour is as chilling as any spectral activity

SCOTT ALSWORTH suggests that video games have a lot to learn the rich tradition of Marxist theatre

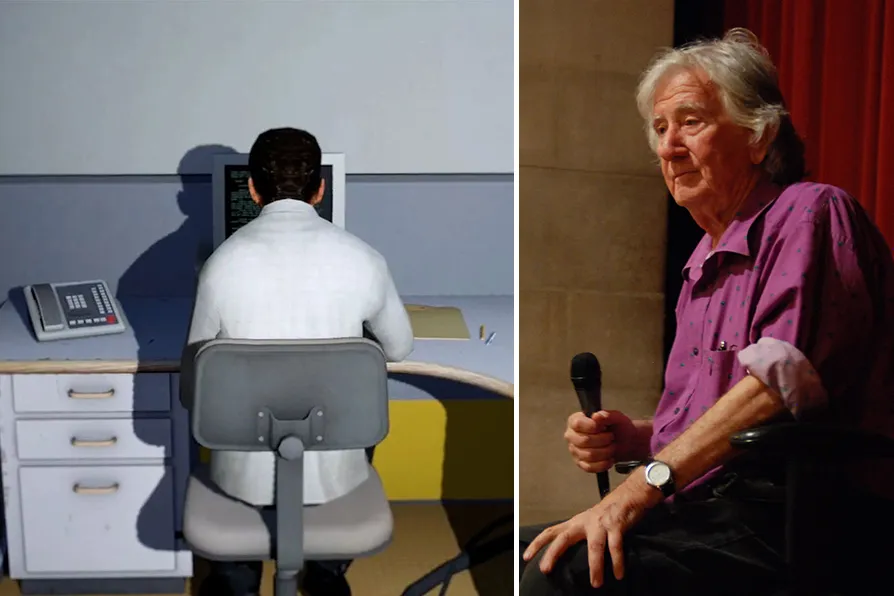

ALIENATION EFFECT: (L) The Stanley Parable; (R) Augusto Boal, 2008 [Pics: Courtesy of Galactic Cafe; Jonathan McIntosh/CC]

ALIENATION EFFECT: (L) The Stanley Parable; (R) Augusto Boal, 2008 [Pics: Courtesy of Galactic Cafe; Jonathan McIntosh/CC]

I AM just going to say it: videogames have a lot to learn.

Not so much from the art of play, but from the arts in general. Of course, it’s true that the film form has managed to make some inroads. Countless titles nowadays can be described as “cinematic” and the language of the silver screen abounds in “cutscenes,” “post-processing,” “credit rolls” and so forth.

However, outside of a few game studies scholars, no-one’s really considering things like Soviet montage or Italian Neorealism. And certainly, no-one appears remotely interested in the “partisan poetry” Engels writes of. Or the works of Aeschylus and Aristophanes, Dante and Cervantes, or the political problem dramas of the 19th century. The plastic arts are similarly marginalised; working-class architecture, sculpture and painting scarcely get a look in.

Our culture, as far as it exists in the ludomanic echo chamber of mainstream videogame development, is muted. And theatre’s no exception.

Yet, it’s precisely this — theatre, and Marxist theatre in particular — that can rescue digital entertainment from itself and inaugurate a revolutionary tendency.

That, I’m sure, sounds like something of a stretch. To think that the innovations of playwrights such as Bertolt Brecht, and in England, Caryl Churchill, Trevor Griffiths and the brilliant Edward Bond, might ever be transposed and redeemed in simulated realms seems absurd.

Still, hear me out. There are some exciting, untapped convergences between videogames and theatre that could be right around the corner.

This brings us to the late dramatist and Brazilian activist, Augusto Boal. Imprisoned and tortured by his country’s dictatorship in 1971 for his radical views, he subsequently reinvented stage drama in exile, pioneering the Theatre of the Oppressed, and within that, his fascinating technique of Forum Theatre.

Influenced by Brecht, he pursued the German theorist’s famous Verfremdungseffekt, or “alienation effect,” to its inevitable conclusion: interactivity. Where previously the fourth wall had been broken, Boal brought it down completely.

The process, as he devised it, was very simple: perform a short, five-minute play from start to finish where a protagonist suffers a relatable, social injustice. Then immediately re-enact it, exactly as before — only this time with a mediator present, who serves as a go-between for the audience and the stage.

During the second run-through, a spectator — or in Boal’s empowering term “spect-actor” — is allowed to shout “Stop!” to freeze the action. They then replace the protagonist in a bid to resolve their situation while the rest of the cast stay in character and improvise. If one intervention doesn’t work, the play can be restarted, or fast-forwarded, or rewound by someone else, with new attempts being tested and discussed. In short, Boal’s approach is a sort of “discovery learning.” A rehearsal for real-world resistance.

It’s also an approach that mirrors the core “try, fail, retry” loop of videogames and, to sneak in a term from gaming parlance, “save scumming.” That is, constantly saving progress to get past a game’s difficult bits.

In principle, then, we might one day hope to see Boalian theatre on our Xboxes and Playstations. Conceivably with AI and quantum computers doing the non-generative, heavy lifting: reacting to “spect-actor” input and weaving together scripted content, and modelling dynamic working-class scenarios where we can anatomise struggles in society.

So, imagine rewinding and replaying an altercation with a boss, say, or a legal dispute with a police officer at a protest, or an argument at a hustings. The possibilities are endless.

And, you know, this is to take one example from many. Theatre offers videogames plenty of other vectors, too. We’ve already mentioned Brecht’s alienation effect — can you imagine the potential there for interactive media?

In fact, if you’re curious, you don’t have to imagine, you can just give Galactic Cafe’s The Stanley Parable a go. It’s literally epic theatre for the 21st century, in videogame format. You can even download it on your phone.

While exploring Kafkaesque themes of isolation, helplessness and absurdity, it also borrows liberally from Brecht’s bag of tricks to detach players from a “culinary” gaming experience. There is, for instance, sparse set design and forensic lighting, a refusal to conceal stage machinery — or rather, the virtual playscape — and a narrator-author, who will be the first to remonstrate with you if you don’t follow the plot.

It all combines to impress critical distance, to provoke. Indeed, in one scene, where the eponymous Stanley faces death by a compacting machine, a second narrator explains that the only way to really “beat” the game is to turn it off.

And perhaps that’s to get to the heart of it. In subversive theatre, as in videogames, maybe it’s not about losing ourselves in art, but being challenged to find the right way forwards.