Tyrannosaurs in Thailand, colonialism as videogame, and a feminist gem from 1936

ANDY HEDGECOCK relishes a graphic portrayal of the corrosive impact of commodification, but can’t sympathise with the characters

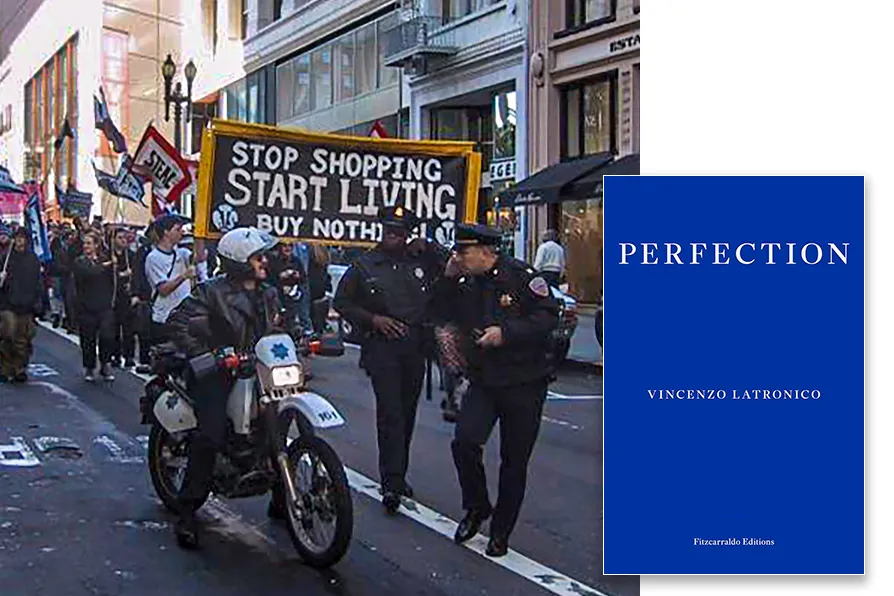

ANTI-CONSUMERIST DEMO: Buy Nothing Day demonstration, in downtown San Francisco, 2000 [Pic: Lars Aronsson/CC]

ANTI-CONSUMERIST DEMO: Buy Nothing Day demonstration, in downtown San Francisco, 2000 [Pic: Lars Aronsson/CC]

Perfection

Vincenzo Latronico, Fitzcarraldo, £12.99

PSYCHOLOGIST Edgar Rubin produced a visual illusion to demonstrate the doubleness of perception. Viewers see a vase, which switches to a pair of faces, then it’s a vase once more.

Perfection, Vincenzo Latronico’s fourth novel and his first to be translated into English, is the literary equivalent of Rubin’s Vase. It elicits admiration and irritation by turns.

Latronico has rewritten and updated Things: A Story of the Sixties (1965) by French experimentalist Georges Perec — a writer who embedded socio-political critique in literary games.

The similarities between Perfection and Things are striking. Both writers consider the impact of consumerism in shaping and limiting our lives; and both explore the theme through complex mosaics of imagery rather than detailed plotting or in-depth studies of character. There are structural correspondences too — openings based on extensive inventories of objects and closing sequences lurching into the future tense to compare actual and desired states of being.

Redeploying tools and techniques considered innovative in an earlier period is fraught with risk. Success depends on finding new meaning in an altered context.

The outcome of Latronico’s project is technically impressive. His prose is vivid but spare: urban landscapes, interior spaces and the ceaseless transformations of onscreen images are described with clarity and in unflinching detail.

Anna and Tom, young expat creatives living in Berlin in the 2010s, are obsessed with their quest for an ideal existence. They engage in a carefully curated set of activities — exhibition openings, slow cooking, visits to sex clubs, half-hearted orgies, unfocused political activism, collecting limited edition LPs and furnishing their flat.

Ostensibly, the couple lead lives of ease and luxury, but there’s a problem: nothing is experienced spontaneously, every aspect of their existence is measured against a set of shifting ideals, transmitted to them via electronic media.

Taste is everything, but it is volatile. Anna and Tom don’t have a clear idea of what they ought to desire. As a result, their enthusiasms are desultory, and lying just below the glossy surface of their lifestyle is an overwhelming sense of disengagement and exhaustion. Even the unsimulated joy they take in each other is undermined by the ceaseless storm of imagery around them.

Latronico’s graphic portrayal of the corrosive impact of commodification is the book’s strong suit. He captures the emptiness, frustration and confusion of Anna and Tom’s lives with laudable restraint: we’re allowed to draw our own conclusions based on his detailed descriptions (facilitated by Sophie Hughes’s elegant translation).

But, like Anna and Tom’s striving for a nebulous notion of perfection, Latronico’s enterprise has serious flaws at its heart. The focus on process and commodity distances us from the characters — we come to see them as an organic form of lifestyle accessory and cease to care about their sense of existential desolation.

Another issue lies in Latronico’s departure from the strategy adopted by Perec. In the source novel characters received no mercy from their author, there was clear satirical intent in portraying their descent into lives of escapism, vacuity and, to borrow a phrase from Thoreau, quiet desperation. Latronico is less judgemental in relation to Anna and Tom but, curiously, not remotely kind towards them. Oppressed and consumed by the notion that aspects of their lives can be “optimised,” they are effectively without agency and any form of emotional engagement with them becomes impossible.

Perfection is beautifully written, clever and utterly dispiriting. It has no central thesis but provides an impressive description of a malaise affecting a privileged segment of the world’s population. In an era of resurgent fascism, climate crisis and genocide, it’s hard to care about the ennui of Anna and Tom.