STEPHANIE DENNISON and ALFREDO LUIZ DE OLIVEIRA SUPPIA explain the political context of The Secret Agent, a gripping thriller that reminds us why academic freedom needs protecting

PETER MASON is beguiled by a fascinating account of the importance of cricket to immigrants from the Caribbean to the UK

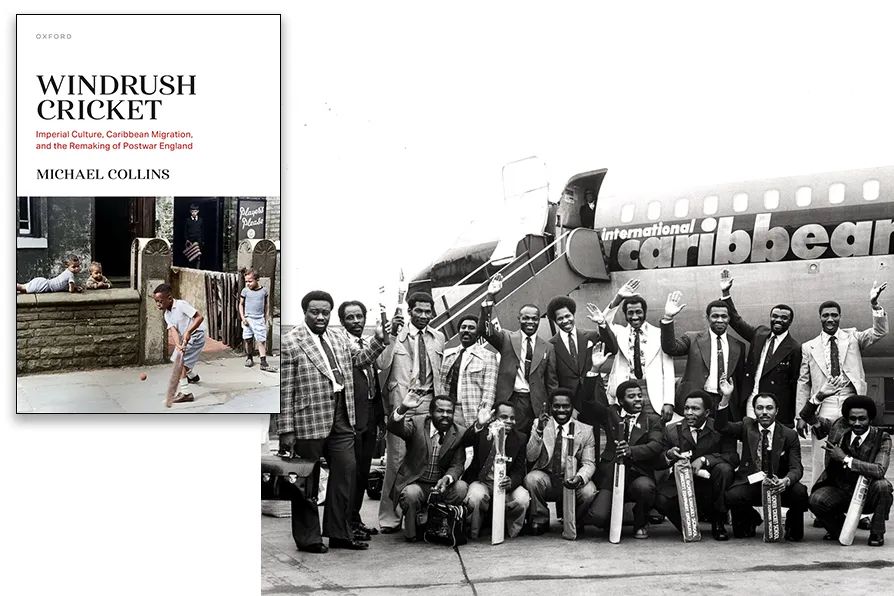

The London-based CRS Cardinals team prepares to leave for a tour of Barbados [Pic: Courtesy of London Transport Museum]

The London-based CRS Cardinals team prepares to leave for a tour of Barbados [Pic: Courtesy of London Transport Museum]

Windrush Cricket

Michael Collins, Oxford University Press, £30

THE core of this welcome new book is a fascinating account of how immigrants from the Caribbean in the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s used cricket as a vehicle to try to win themselves a foothold in British society.

Little has been written about this facet of the “Windrush experience,” and some might question whether it could justify a whole book to itself. But the author, an associate professor of history at University College London (UCL), argues that cricket, along with non-conformist churches and West Indian social clubs, was fundamental to the way in which early arrivals from the Caribbean were able to establish a presence in post-war Britain on their own terms.

The first self-organised West Indian cricket team in Britain, Leeds Caribbean, was formed in the same year that the Windrush ship arrived, 1948, and indeed was set up by several men who had travelled across on that vessel.

Over the next 30 years a plethora of other clubs were established all around the country, from New Calypsonians and Island Taverners to Paragon, Starlight and Holmwood.

They were formed partly as a response to the unwelcoming environment of existing clubs throughout the land, and Michael Collins argues that they acted not just as a safe space to play the game but as hubs for “self-help, support services and the development of social capital,” where members could find out about jobs, housing and how to negotiate their new lives in a strange land.

For a second generation, born in Britain, the teams performed slightly different functions, including as a refuge from racism in other spheres, while continuing to go from strength to strength. At the height of their popularity, according to Collins’s research, there were perhaps 150 such clubs by the late ’70s and early ’80s.

From that point onwards, however, the numbers have dwindled dramatically, partly thanks to societal factors but also due to the decline in prowess of the West Indies Test team, which once drove interest in the game among young black Britons. Sadly, Collins concludes that there’s no way back now, and that the downward curve for Caribbean clubs will almost certainly continue.

The best bits of this accessibly written account are the personal stories behind the wider picture — of friendships developed and self-esteem bolstered. These leaven the more academically inclined contextualising, in particular in teams of the era before the post-Windrush boom, when a smaller number of early 20th century West Indian immigrants, less threatening to the majority, were better able to gain some kind of acceptance through cricket.

While it would have been nice to hear more of the human interest tales — not least because the overall narrative sometimes becomes depressingly anchored in the idea of constant struggle — Collins is clearly, and correctly, committed to giving the Windrush cricket story a theoretical underpinning that allows an investigation of the subject matter in all its complexities.

In any case, the hope is that some of the more engaging material will emerge separately as part of a connected Caribbean Cricket Archive that has been developed by Collins and colleagues at UCL. Seeking memories, information and anecdotes from participants in the glory years of those pioneering clubs, that ongoing project promises to be a valuable companion to this admirable book.

MARJORIE MAYO welcomes an account of family life after Oscar Wilde, a cathartic exercise, written by his grandson

PETER MASON is surprised by the bleak outlook foreseen for cricket’s future by the cricketers’ bible