JOHN GREEN, MARIA DUARTE and ANGUS REID review Fukushima: A Nuclear Nightmare, Man on the Run, If I Had Legs I’d Kick You, and Cold Storage

WILL PODMORE peruses a new history of the opening weeks of conflict between Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia

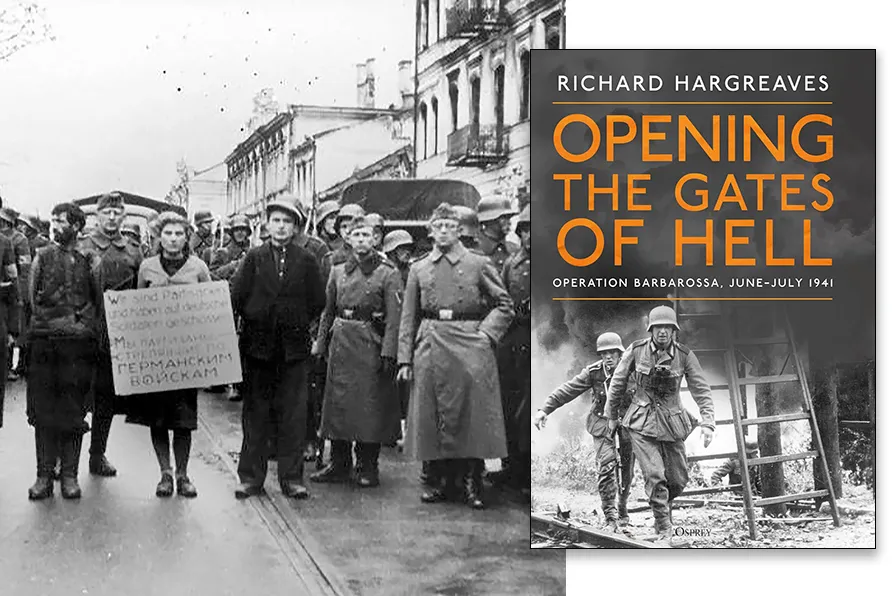

Masha Bruskina, a nurse with the Soviet resistance, before her execution by hanging. The placard reads: 'We are the partisans who shot German troops', Minsk, 26 October 1941 [Pic: German Federal Archives/CC]

Masha Bruskina, a nurse with the Soviet resistance, before her execution by hanging. The placard reads: 'We are the partisans who shot German troops', Minsk, 26 October 1941 [Pic: German Federal Archives/CC]

Opening the Gates of Hell: Operation Barbarossa, June-July 1941,

Richard Hargreaves, Osprey, £30

ON June 22 1941 Nazi Germany began its invasion of the Soviet Union. This history of its first weeks is based on a decade’s research, into official documents, personal diaries and letters, court papers, newsreels, newspapers and memoirs.

This was to be, in Hitler’s words: “a war of extermination.” Herbert Backe, Hitler’s minister for food, spelt out the infamous “Hungerplan” — “many tens of millions of people will be superfluous and will die.”

Erich Hoepner, commanding the armed forces aimed at Leningrad, told his soldiers: “The goal of this struggle must be the disintegration of present-day Russia — and there it must be waged incredibly brutally. In its conception and execution, each clash must be guided by an iron will and lead to the ruthless, total destruction of the enemy. In particular, no mercy is to be shown the bearers of the current Russian-Bolshevist system.”

Guidelines for the Wehrmacht laid down the way the troops should see the Bolsheviks: “We would be insulting animals if we were to call the features of these slave-drivers — a high percentage of them Jewish — animal-like. They are the embodiment of the infernal, the personification of the insane hatred of all that is noble in mankind.”

This open anti-semitism contrasts with Soviet practice. As Hargreaves notes, when Soviet forces occupied the Baltic states before the Nazi invasion: “Suddenly, Jews found many of the restrictions on their lives and careers lifted. No longer were they prevented from holding ministerial posts, working in the civil service, in the legal system, in the media, in the police, the new co-operatives and Soviet government apparatus.”

Just three days into the war, the Soviet government decided to move key industries from the cities of Ukraine and European Russia to the far east of the Soviet Union. In four months, over 1,500 factories were relocated. Despite the loss of land, resources and workers, and despite the disruption, Soviet factories produced twice the number of aircraft, and two-and-a-half times the number of tanks in the second half of 1941 as they did in the first half.

But far too many in eastern Europe aided the Nazis and killed Jews. There were pogroms in Latvia, Lithuania, Ukraine and Romania. The Lithuanian historian Zenonas Ivinskis noted: “The majority of people — certainly the ones I encounter — long for the Germans to march in. Then the slaughter of the Jews would begin in earnest.” Another Lithuanian agreed: “The mood is such that the majority of people want the Germans to come. And then the killing of the Jews would begin.”

A popular song among Ukrainian nationalists went “Death, death to the Poles, death to the Jewish-Muscovite commune.” The Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists in Lviv urged: “Destroy the enemy. People! Know! Moscow, Poles, Hungarians, Judaism — these are your enemies. Destroy them.” A German security report claimed 7,000 Jews were killed.

During a pogrom in Zloclow in Ukraine, a German officer concluded: “The Russians brought these murders upon themselves with their bestial actions.” The Wehrmacht aided the pogroms, but another German officer could still boast of “our clean, decent lives.”

As Hargreaves acknowledges: “The indignation and patriotic fervour which seized most Russians was genuine.” The war in the east was far harder than any of Hitler’s previous campaigns. The first 10 days of Barbarossa cost the Reich 54,000 casualties, 11,822 killed. By mid-August, one in every 10 German soldiers in the east had become a casualty, with over 375,000 killed or wounded.

A German veteran of World War I asked: “What has become of the Russian of 1914-17, who ran away or approached us with his hands in the air when the firestorm reached its peak? Now he remains in his bunker and forces us to burn him out, he prefers to be scorched in his tank, and his airmen continue firing at us even when their own aircraft is set ablaze. What has become of the Russian? Ideology has changed him.”

The first-person accounts provide a vivid picture. Yet to my mind this book adds little to the classic accounts by John Erickson, David Glantz and David Stahel.

But it does show once again that the people and soldiers of the Soviet Union really were fighting to defend the revolution, and their own state, in stark contrast to the Russian army’s failure in the first world war.