GORDON PARSONS is bowled over by a skilfully stripped down and powerfully relevant production of Hamlet

Class discrimination and the arts

VANESSA CORBY asks what will the arts do for everyday working people?

ON the morning of July 5, Keir Starmer and his supporters celebrated Labour’s election victory in the Turbine Hall of London’s Tate Modern, bathed in the glow of a huge red wall behind.

Hard on the heels of the culture wars of the Conservative election campaign and its “rip-off degrees” rhetoric, this iconic start felt like stepping into a parallel universe.

More from this author

The phrase “cruel to be kind” comes from Hamlet, but Shakespeare’s Prince didn’t go in for kidnap, explosive punches, and cigarette deprivation. Tam is different.

ANGUS REID deconstructs a popular contemporary novel aimed at a ‘queer’ young adult readership

A landmark work of gay ethnography, an avant-garde fusion of folk and modernity, and a chance comment in a great interview

ANGUS REID applauds the inventive stagecraft with which the Lyceum serve up Stevenson’s classic, but misses the deeper themes

Similar stories

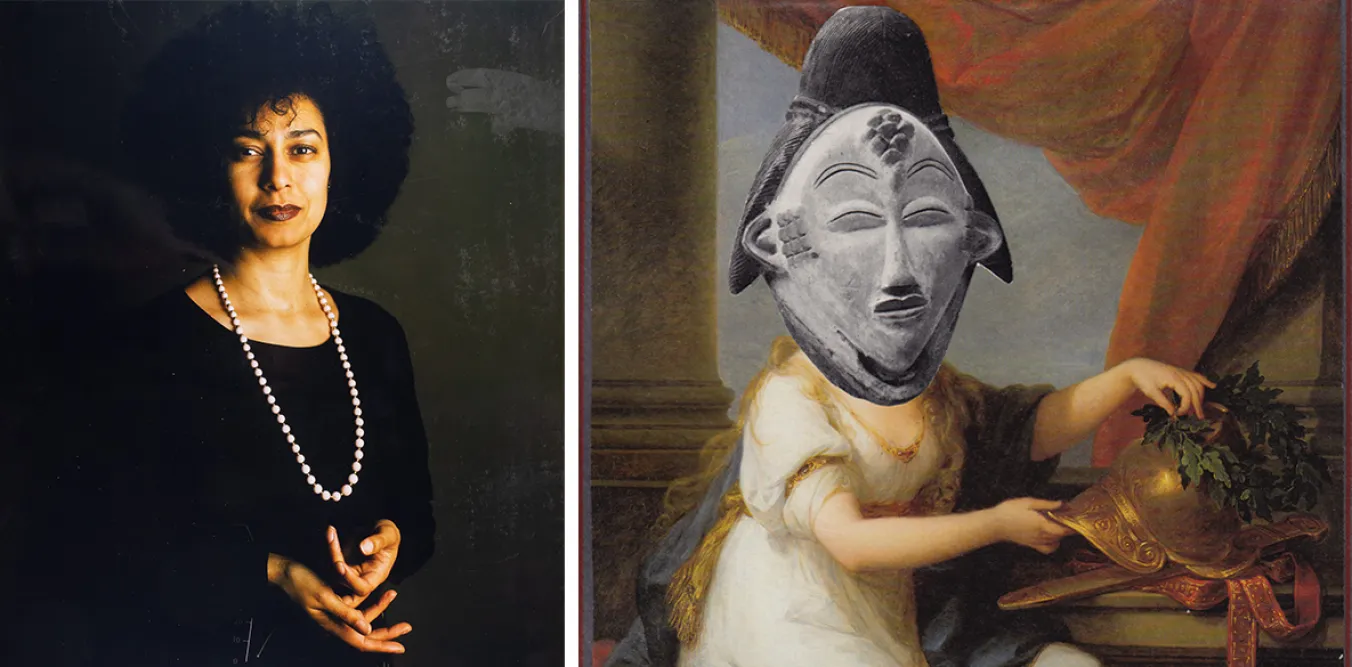

JOE JACKSON explores how growing up black amid ‘the quiet racism of Scotland’ shaped the art and politics of Maud Sulter

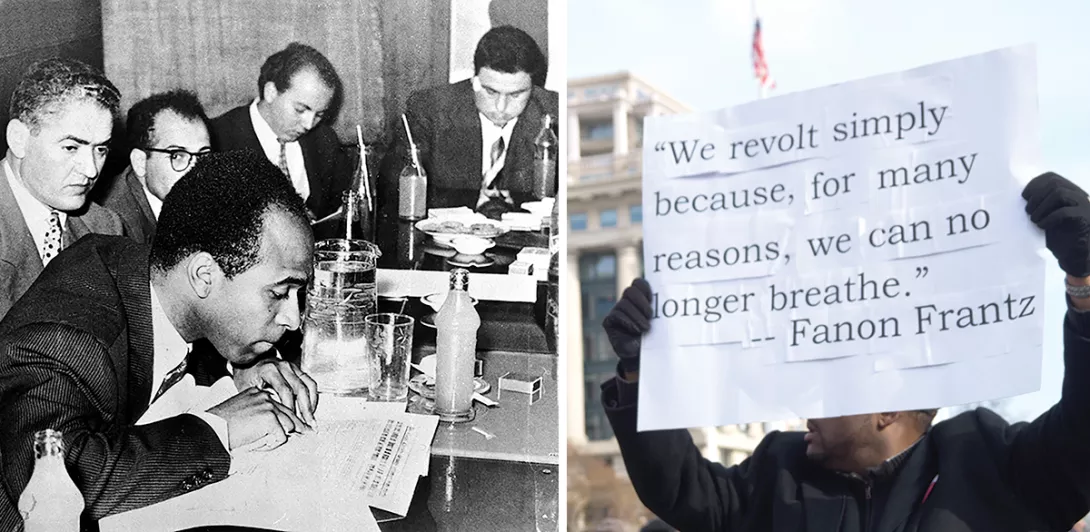

The Wretched of the Earth has been translated into South Africa’s Zulu language. Its translator MAKHOSAZANA XABA explains why Frantz Fanon’s revolutionary book still matters and why is it important that books like this be available in isiZulu

ABAYOMI AWELEWA celebrates AKINWANDE OLUWOLE SOYINKA, the legendary African author whose work shows the powerful role of the arts in challenging oppression, advocating for justice and inspiring social change

BLANE SAVAGE tours an exhibition that highlights the revolutionary work of Britain’s leading pop artist