ANDY HEDGECOCK relishes two exhibitions that blur the boundaries between art and community engagement

The long shadow of a masterpiece

JENNY FARRELL celebrates the continuing relevance of the first English-speaking playwright of proletarian origin to create world theatre

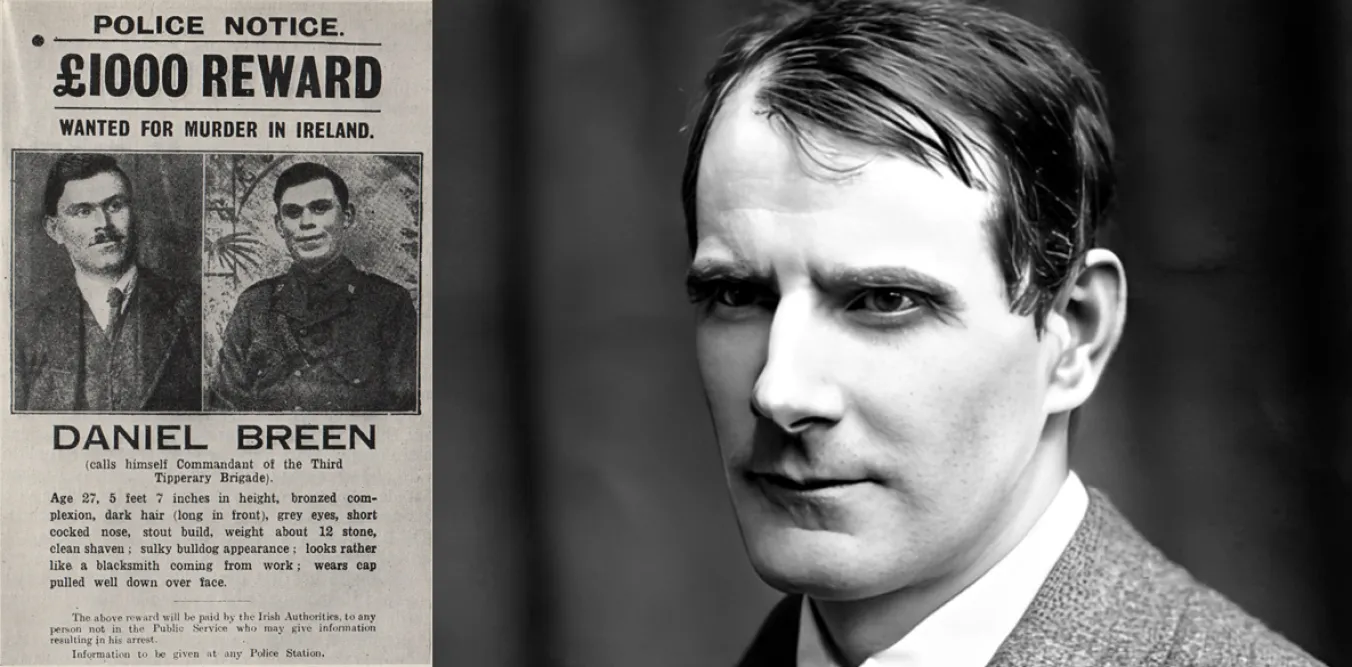

SEAN O’CASEY’s play The Shadow of a Gunman premiered 100 years ago, on April 12 1923, at Dublin’s national Irish theatre, the Abbey Theatre.

The theatre, which grew out of the Irish Renaissance movement for the renewal of Irish literature in 1904, encouraged new Irish writers and provided a platform for the exploration of progressive ideas on stage.

The Shadow of a Gunman is the first of O’Casey’s three Dublin plays, which examine the maturity and fortunes of the people at three important moments in Irish history — the Easter Rising (1916), the war of independence (1918-21), and the civil war (1922-23) — all of which O’Casey experienced.

More from this author

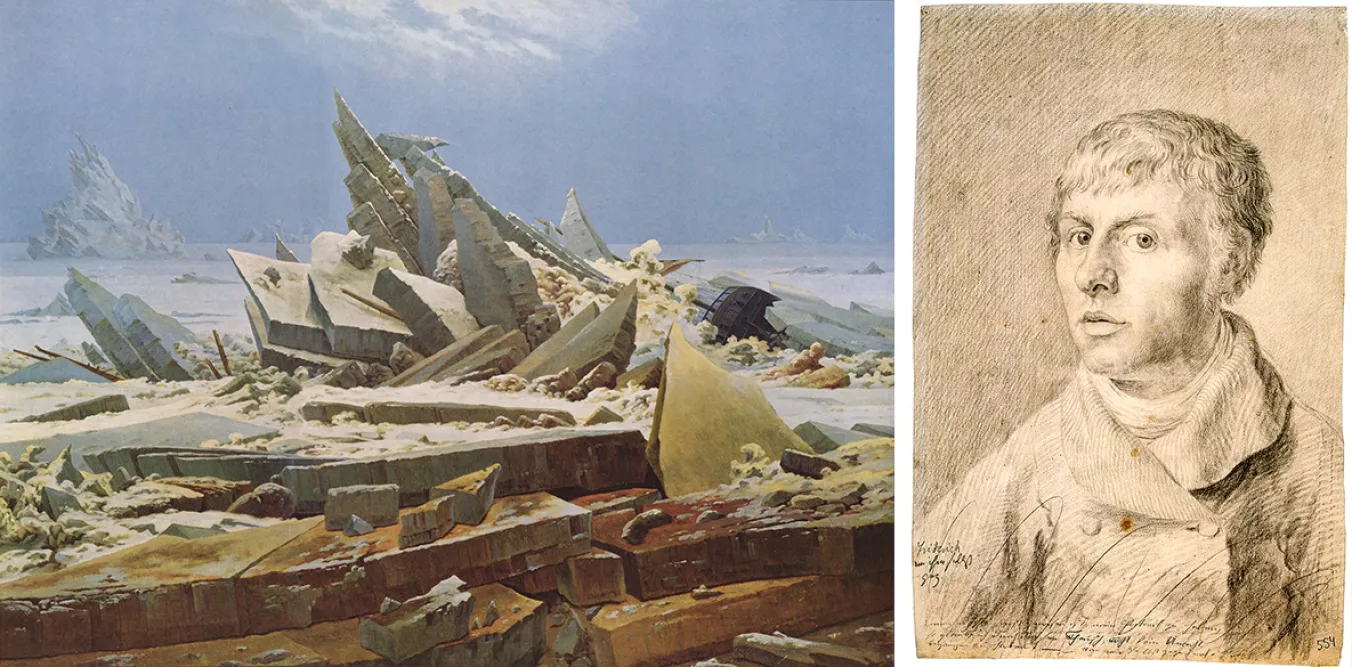

As Caspar David Friedrich’s 250th anniversary is celebrated in Berlin and New York, JENNY FARRELL urges viewers of the German Romantic painter to understand its true historical context, and beware its co-option by the far-right

As Caspar David Friedrich’s 250th anniversary is celebrated in Berlin and New York, JENNY FARRELL urges viewers of the German Romantic painter to understand its true historical context, and beware his co-option by the far right

JENNY FARRELL traces the critical role that the CPUSA played in the education of Harlem’s greatest man of letters

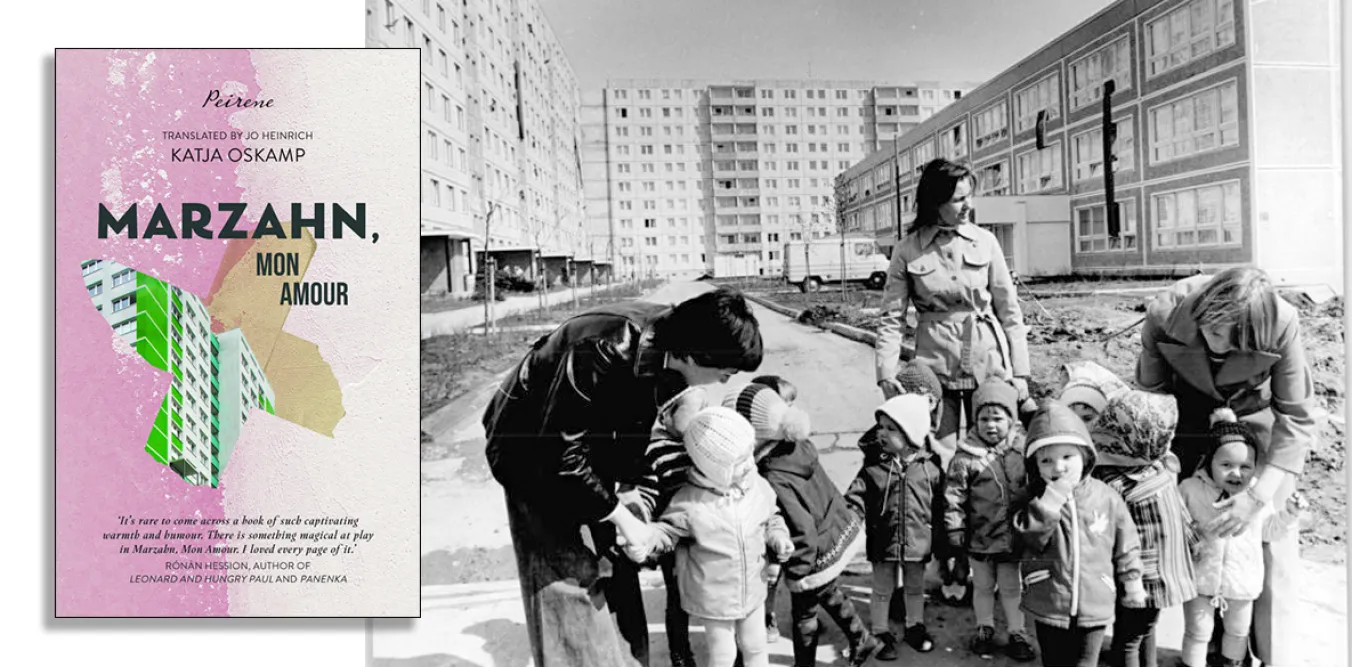

JENNY FARRELL introduces an extraordinary book that maintains the cultural practise of the GDR by writing about ordinary working lives

Similar stories

Taking up social work after being widowed transformed a Victorian liberal into a lifelong fighter for causes as wide-ranging as Sinn Fein and Indian independence to the right of women to drink in pubs, writes MAT COWARD

LYNNE WALSH regrets that unity is denied to a fine cast let down by the baffling spectacle of a poor lead performance

On the 60th anniversary of the playwright’s death JENNY FARRELL draws attention to the potential for revolution portrayed in his little known late work