SUE TURNER is fascinated by a book that researches who the largely immigrant workforce were that built the Empire State

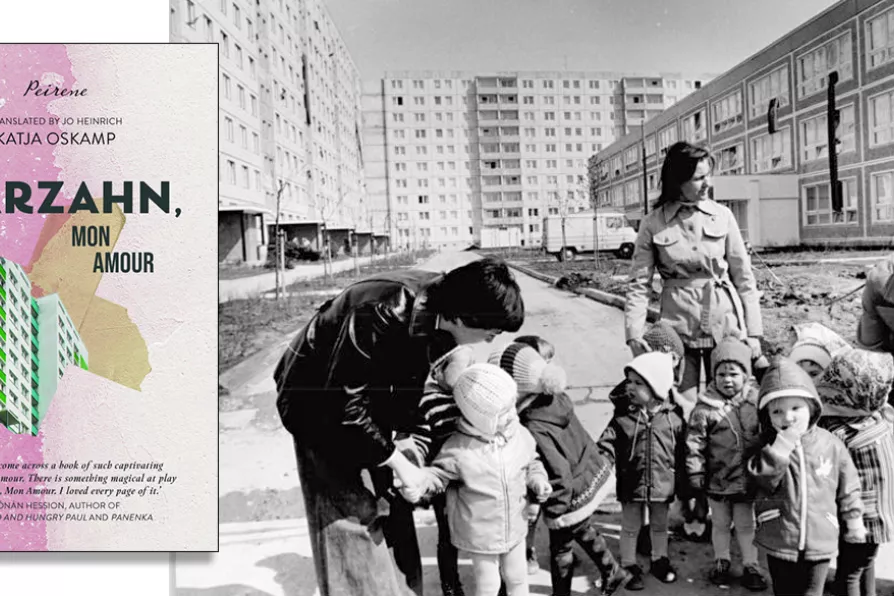

The construction of the Marzahn housing project, 1978

[German Federal Archive/CC]

The construction of the Marzahn housing project, 1978

[German Federal Archive/CC]

Marzahn Mon Amour

by Katja Oskamp, Peirene Press, £12

The winner of the annual International Dublin Literary Award for 2023 is a book by the East German writer Katja Oskamp, Marzahn, Mon Amour. Marzahn was once the GDR’s most ambitious and largest social housing programme, providing homes for over 270,000 people.

The book is firmly rooted in a GDR literary tradition – that of truly valuing the ordinary, everyday lives of people, inseparably linked to the world of work. Perhaps the most famous example in GDR literature is Maxi Wander’s Guten Morgen du Schöne (1977, Good Morning, Beautiful). It presents interviews with 19 women aged between sixteen and ninety-two, talking about their lives.

A similarly themed book of interviews with men by Christine Mueller, Maenner-Protokolle (1985), was later followed by Christa Wolf’s diary-style publication Ein Tag im Jahr (2003, One Day a Year), where she records her own reflections on the same date every year, September 27, 1960-2000.

The decision highlights the tension between freedom of expression and the state’s role in shaping historical memory at former concentration camps, reports LEON WYSTRYCHOWSKI

JOHN GREEN observes how Berlin’s transformation from socialist aspiration to imperial nostalgia mirrors Germany’s dangerous trajectory under Chancellor Merz — a BlackRock millionaire and anti-communist preparing for a new war with Russia

GORDON PARSONS is fascinated by a unique dream journal collected by a Jewish journalist in Nazi Berlin