TONY BURKE speaks to Gambian kora player SUNTOU SUSSO

NLR - wtf?

WILL PODMORE is glad to find that a survey of editorials exposes the pretentions of the New Left Review

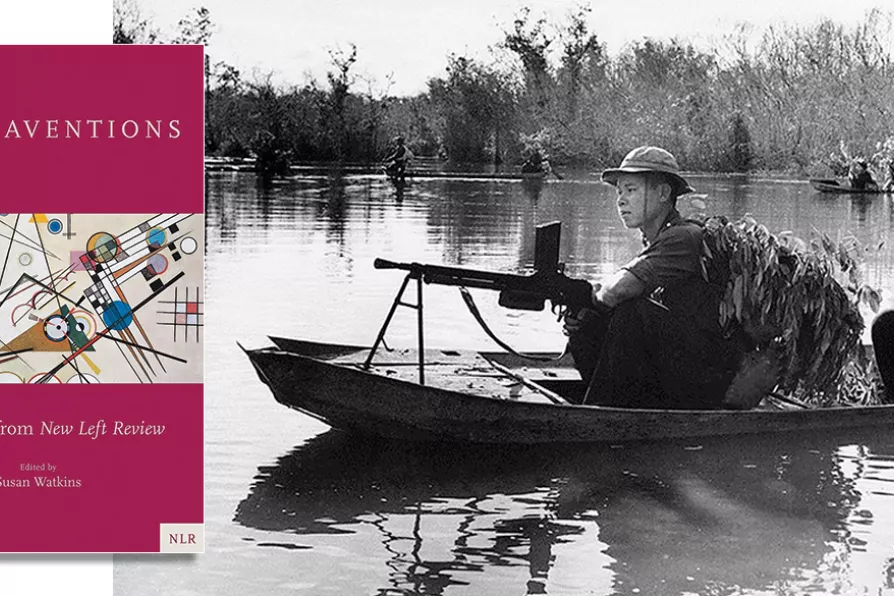

TRUE VICTORS: National Liberation Front of South Vietnam guerrillas patrol the Saigon River in October 1966

[Public Domain]

TRUE VICTORS: National Liberation Front of South Vietnam guerrillas patrol the Saigon River in October 1966

[Public Domain]

Contraventions: editorials from New Left Review

Susan Watkins, Verso, £25

THIS selection of editorials from the New Left Review in the years from 2000 to 2022 reveals more about NLR’s ideology than was possibly intended.

The self-important NLR team has always seen its role as indispensable — to inject correct theory into the somnolent masses. NLR’s philosopher-kings will enlighten the benighted masses across the world. There is no need for all the hard work of building a party, which it sees as inevitably doomed to bureaucratic deformation.

Similar stories

LOGAN WILLIAMS believes there are lessons to be learned from Vietnam’s education system whose excellence is recognised internationally

From McCarthy’s prison cells to London’s carnival, Jones fought for peace and unity while exposing the lies of US imperialism, says ROBERT GRIFFITHS, in a graveside oration at Highgate Cemetery given last Sunday

CARLOS MARTINEZ welcomes the publication of the writings of the great Palestinian author, political theorist and spokesman for the PFLP

Morning Star editor BEN CHACKO reports from the annual Rosa Luxemburg Conference held last weekend in Berlin