GORDON PARSONS is bowled over by a skilfully stripped down and powerfully relevant production of Hamlet

The disillusion of a top BBC journalist

JOHN GREEN is disappointed by a marred critique of the British establishment by someone who was part of it

Strangeland – How Britain Stopped Making Sense

Jon Sopel, Ebury Press, £22

FROM the start, I was sceptical about this book. After all, someone like Jon Sopel, who was for many years a top BBC correspondent — for eight years its man in Washington — must be completely in tune with Establishment ideology or he would not have been given such a job.

Here he takes a critical look at a country that has dramatically changed since he left it in 2014. “Returning to the UK in some ways has been disconcerting,” he writes. “It is, after all, my home; a country I love and am proud of. But either it’s changed, or I have. Maybe both. It just feels like a strange land. This book is, I suppose, about Britishness — the values that have guided us.”

More from this author

The phrase “cruel to be kind” comes from Hamlet, but Shakespeare’s Prince didn’t go in for kidnap, explosive punches, and cigarette deprivation. Tam is different.

ANGUS REID deconstructs a popular contemporary novel aimed at a ‘queer’ young adult readership

A landmark work of gay ethnography, an avant-garde fusion of folk and modernity, and a chance comment in a great interview

ANGUS REID applauds the inventive stagecraft with which the Lyceum serve up Stevenson’s classic, but misses the deeper themes

Similar stories

Despite mainstream political podcasts drowning in centrist drivel, Labour Left Podcast offers an authentic grassroots perspective from decades of working-class struggle and resistance, writes SOLOMON HUGHES

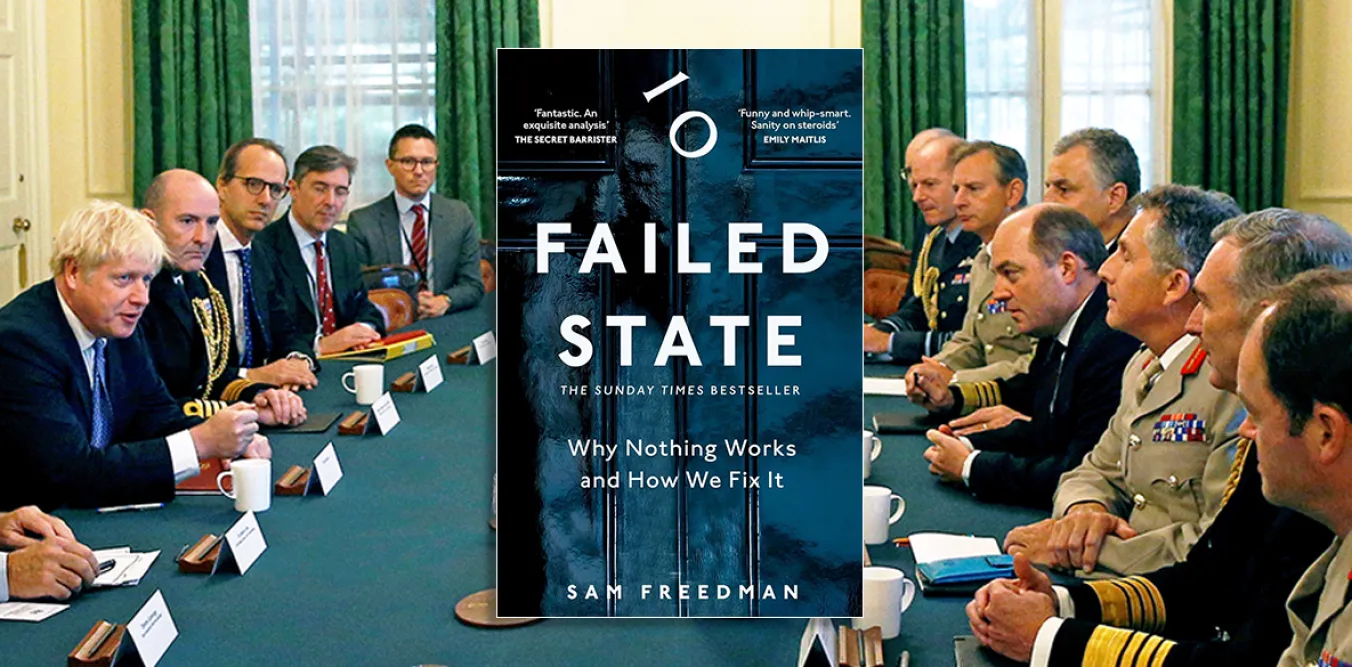

JOHN GREEN welcomes a significant contribution to the discussion of the urgent need to reform Britain’s failed governmental system

In the third of his four-part series on the general election, PETER KENWORTHY looks at Keir Starmer's moves to shift Labour right, and how some independent candidates used that to challenge the party

With respect for the authors’ intentions, JOHN GREEN demonstrates the lack of class consciousness that undermines their critique of dysfunctional Britain