ALAN McGUIRE welcomes a biography of the French semiologist and philosopher

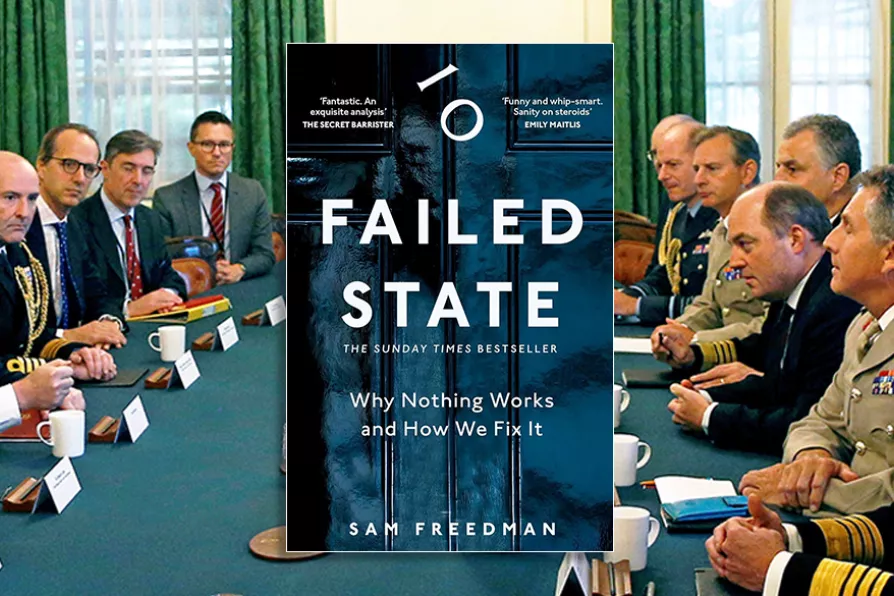

EXCESSIVE POWER: Prime Minister Boris Johnson during a meeting with military service chiefs at 10 Downing Street, London, September 2019

EXCESSIVE POWER: Prime Minister Boris Johnson during a meeting with military service chiefs at 10 Downing Street, London, September 2019

Failed State – Why Nothing Works and How We Fix it

By Sam Freedman, Macmillan, £20

FREEDMAN was until 2007, a member of the Labour Party, and has spent much of his working life at the heart of government, both as a civil servant in the Department for Education as a senior policy adviser to Michael Gove and as adviser to the leader of the then opposition. This, his first book, argues persuasively that the British government is not fit for purpose and explains in detail why.

He is not a Marxist and offers no class analysis, but it would by asinine to dismiss his critique on that basis. He provides an incisive analysis of what is wrong with our present system from an insider’s viewpoint. He argues that modern British history is best thought of “not as a story of decline but of a repeating series of crises that are eventually resolved.” “Our problem,” he goes on, “is the total failure of our political institutions to deal with the [even] more limited challenges we have.”

LAURA PIDCOCK and PAUL O’CONNELL introduces Rise, a political platform for working-class activism

With turnout plummeting and faith in Parliament collapsing, BERT SCHOUWENBURG explains how radical local government reform — including devolved taxation and removal of party politics from town halls — could restore power to communities currently ignored by profit-obsessed MPs