GORDON PARSONS is bowled over by a skilfully stripped down and powerfully relevant production of Hamlet

Who took dictation?

TOM PIERSCIONEK is fascinated by the place of slaves in the creation of Christian scripture

God’s Ghostwriters: Enslaved Christians and the Making of the Bible

Candida Moss, Little Brown, £25

IT HAS long been accepted by both Biblical scholars and laypersons that a small number of individuals, such as the Gospel authors (Mathew, Mark, Luke and John) and the prolific letter writer St Paul, solely composed large parts of the New Testament.

Candida Moss, biblical scholar and Professor of Theology at the University of Birmingham, shatters this myth in her latest book as she shines a light on the origins of Christian scripture. Moss bestows long overdue credit upon the countless unnamed individuals (many enslaved) who played pivotal roles in composing parts of the New Testament as well as ensuring that Christianity spread across the known world during the precarious climate that existed in the church’s early years.

More from this author

The phrase “cruel to be kind” comes from Hamlet, but Shakespeare’s Prince didn’t go in for kidnap, explosive punches, and cigarette deprivation. Tam is different.

ANGUS REID deconstructs a popular contemporary novel aimed at a ‘queer’ young adult readership

A landmark work of gay ethnography, an avant-garde fusion of folk and modernity, and a chance comment in a great interview

ANGUS REID applauds the inventive stagecraft with which the Lyceum serve up Stevenson’s classic, but misses the deeper themes

Similar stories

Behind headlines of bishops’ resignations and brutal abuse lies the deeper story of class privilege and power, as religious institutions face a stark choice between serving the elite or standing with the oppressed, writes SYMON HILL

Vegetation is growing at an alarming rate on Antarctica’s northernmost region, write ROX MIDDLETON, LIAM SHAW and MIRIAM GAUNTLETT

TOMASZ PIERSCIONEK explores the overlaps between the ideas of Christ and Karl Marx in seeking a better world for the poor and downtrodden

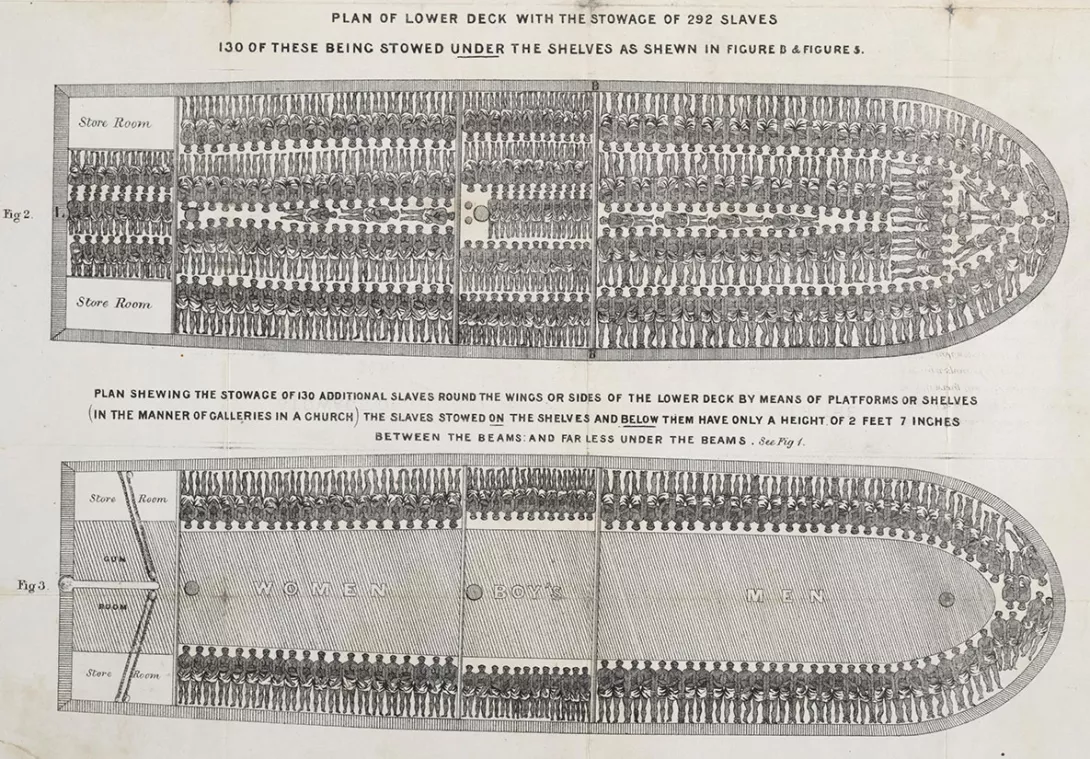

The paltry new fund embraced by the Church of England is nowhere near what real justice demands: handing over the estimated £1.3 billion derived from trafficked Africans to their descendants, explains STEVE CUSHION