GORDON PARSONS is bowled over by a skilfully stripped down and powerfully relevant production of Hamlet

Make it black history year

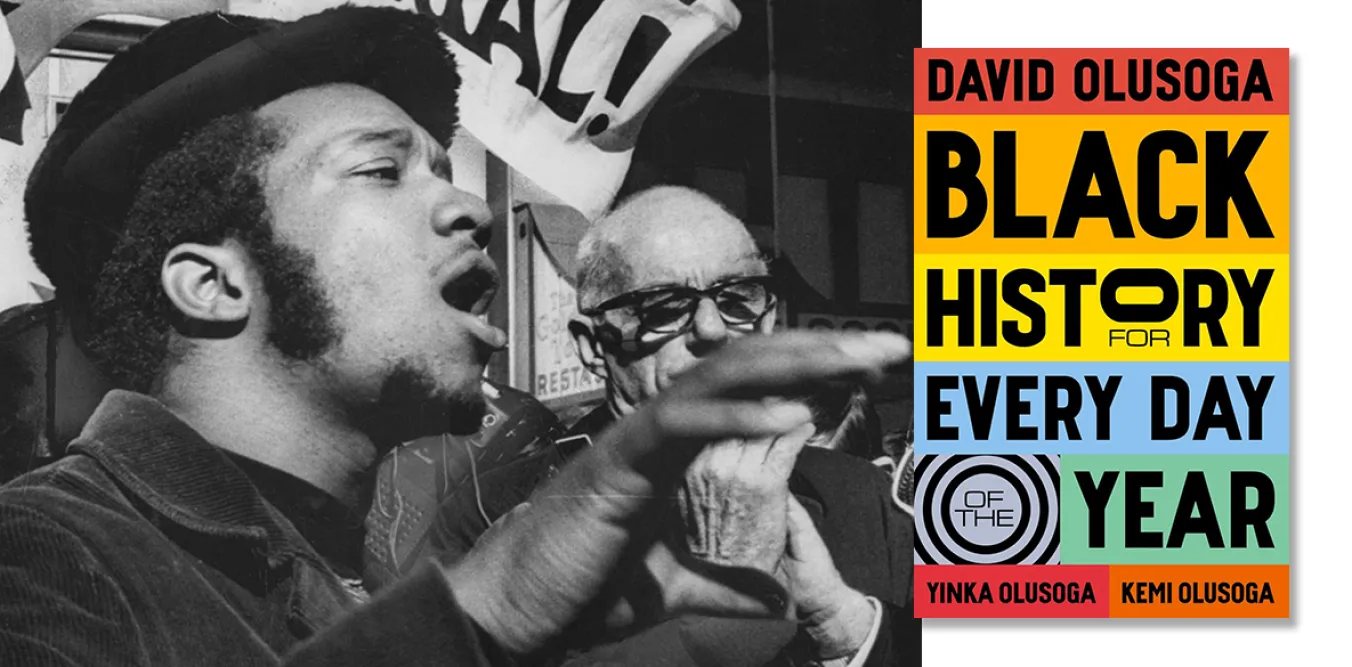

As we celebrate black history month, JENNY WOODLEY recommends an engaging survey of centuries of both injustice and resilience

Black History for Every Day

David, Yinka and Kemi Olusoga, Macmillan, £25

FOR decades, black history in the UK has been siloed from the mainstream, as if incidental to the nation’s history. Black History Month in October is dedicated to celebrating black heritage, but the rest of the year, it feels largely neglected and ignored. Public historian and broadcaster David Olusoga is at the forefront of efforts to integrate black history into our national story.

His latest book, Black History for Every Day of the Year, co-created with two of his siblings, Yinka and Kemi, is another contribution to that work. This attractive and substantial book has an entry for each calendar day detailing an event, person, place, or theme associated with black history.

Similar stories

JOE JACKSON explores how growing up black amid ‘the quiet racism of Scotland’ shaped the art and politics of Maud Sulter

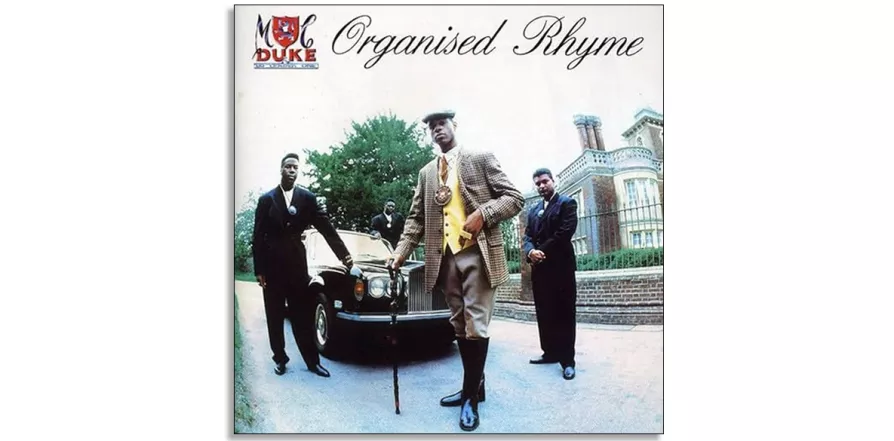

ADAM DE PAOR-EVANS remembers MC Duke: a pioneering British rapper more people should know about

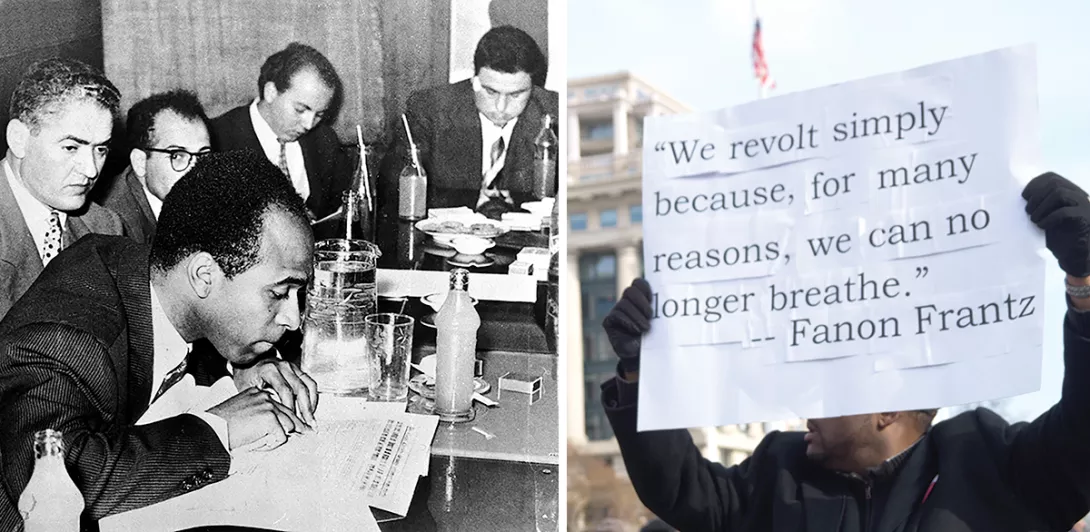

The Wretched of the Earth has been translated into South Africa’s Zulu language. Its translator MAKHOSAZANA XABA explains why Frantz Fanon’s revolutionary book still matters and why is it important that books like this be available in isiZulu

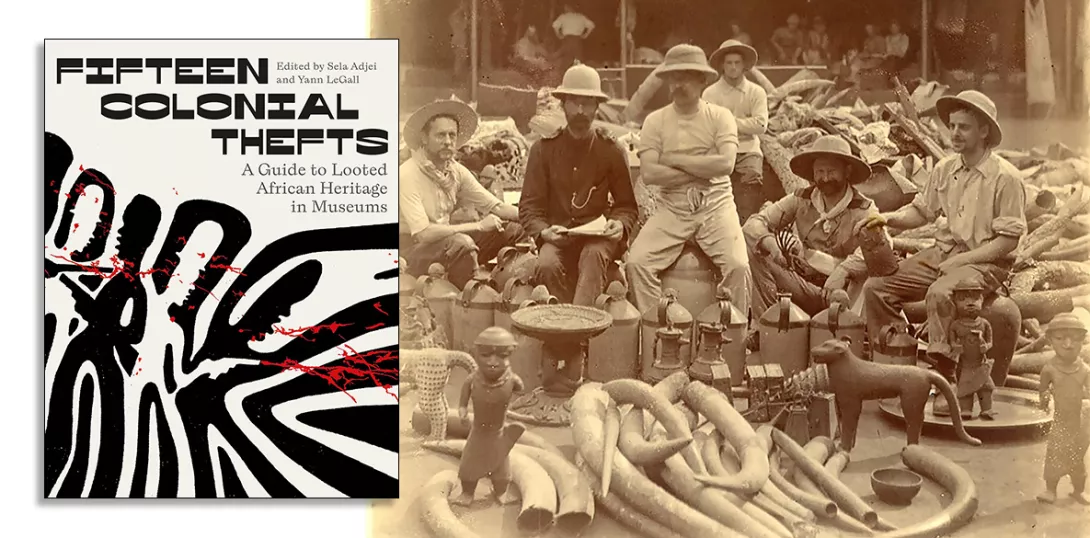

FRANCOISE VERGES introduces a powerful new book that explores the damage done by colonial theft