ANDY HEDGECOCK relishes two exhibitions that blur the boundaries between art and community engagement

‘Peace is not the absence of war, it is a virtue, a state of mind, a disposition of benevolence, confidence, justice’ - Spinoza, Theologico-Political Treatise, 1670

GORDON PARSONS recommends a fine introduction to a philosopher who, like Marx, worked to help society to reject illusion and understand the realities of the human condition

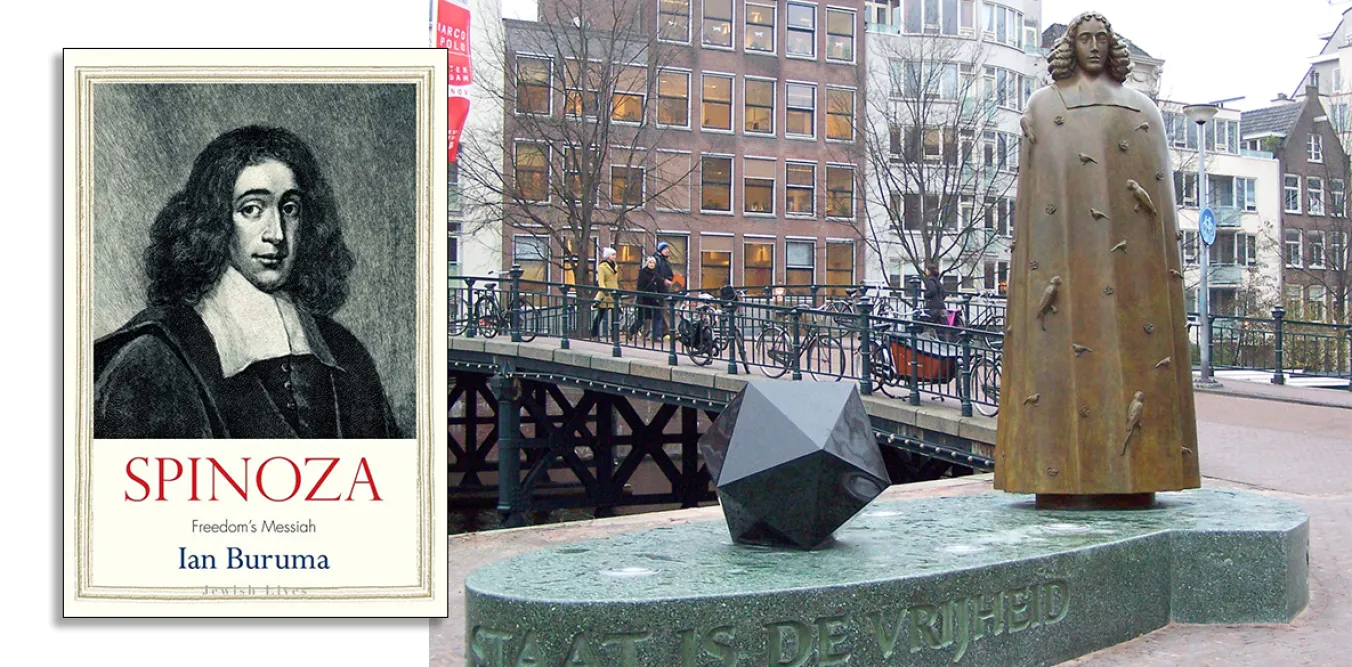

Spinoza: Freedom’s Messiah

Ian Buruma, Yale University Press, £16.99

IT has been observed that Baruch Spinoza does not rate very highly in the popular pantheon of world philosophers and yet, as much as many of his better-known analytical sages, along with Descartes his contemporary, he can be seen to fulfil Marx’s necessary demand that more than interpreting the world, philosophers should strive to change it.

Both were born in the 17th century “Dutch Golden Age,” when Amsterdam became the city at the centre of world trade, science and culture, unlike the rest of Europe where the straightjacket of religious control was imposed by Catholic and various Protestant sects. Indeed, this “city of refuge for Jews, Huguenots, Quakers and other victims of persecution was known as Vrijstad, meaning Freetown.”

More from this author

The phrase “cruel to be kind” comes from Hamlet, but Shakespeare’s Prince didn’t go in for kidnap, explosive punches, and cigarette deprivation. Tam is different.

ANGUS REID deconstructs a popular contemporary novel aimed at a ‘queer’ young adult readership

A landmark work of gay ethnography, an avant-garde fusion of folk and modernity, and a chance comment in a great interview

ANGUS REID applauds the inventive stagecraft with which the Lyceum serve up Stevenson’s classic, but misses the deeper themes

Similar stories

FIONA O’CONNOR recommends a biography of a Portuguese modernist poet who maintained a philosophical approach to his own being and is best encountered within the playfulness of his writing

ALAN McGUIRE recommends a book that tries to shift our understanding of work and our relationship to it

Low pay and spiralling rental costs mean women are all to often trapped in appalling accommodation, writes LYNNE WALSH

NICK MATTHEWS looks at the great Bolshevik leader’s intense three-week period of furious study in the British Library in 1908 and the timeless classic on Marxism and philosophy it produced: Materialism and Empirio-Criticism