GORDON PARSONS is bowled over by a skilfully stripped down and powerfully relevant production of Hamlet

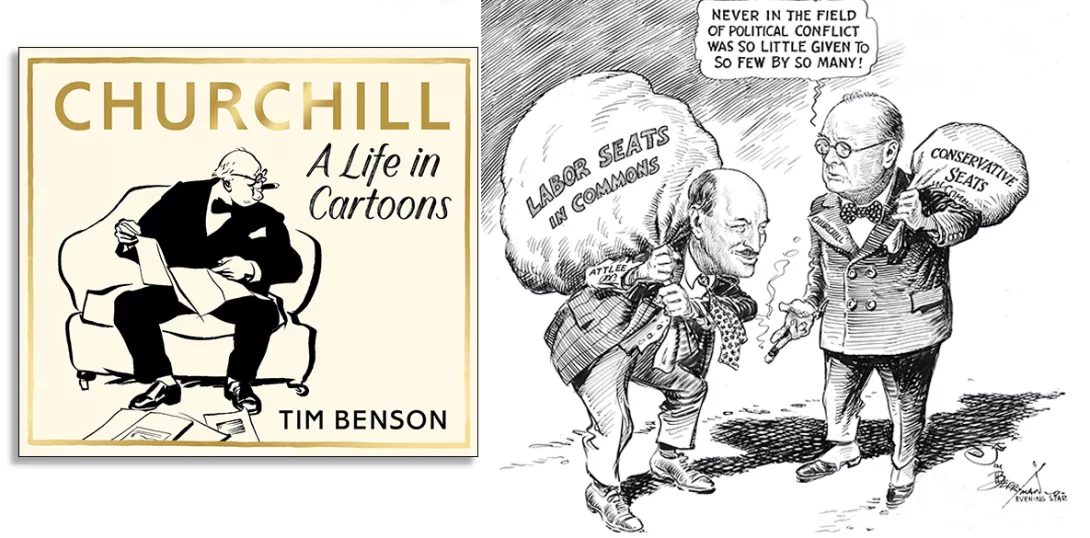

Winnie the lampoon

MALC MCGOOKIN wallows in the artistry of gifted cartoonists given a fine target for caricature

Churchill: A Life In Cartoons

by Tim Benson, Hutchinson Heinemann, £16.99

HERE’s a dinner party ice breaker: Greatest Ever Briton? Discuss!

Apart from a couple of smart arse dinner guests, (“Mister Blobby!”, “Basil Brush!”) it would be mere seconds before “Winston Churchill’ was adamantly offered up.

Churchill, like Wellington, was a brand before advertisers even came up with the concept. Already in his mid 60s when he became prime minister, his energy and phlegmatic character came to define how Britons saw themselves – resolute, implacable, resilient in the face of adversity.

Similar stories

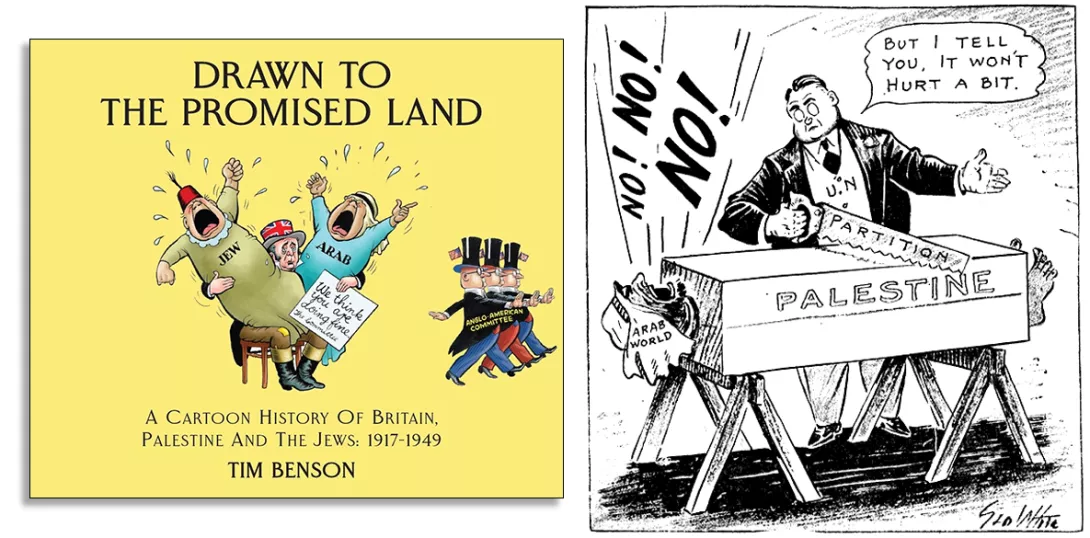

TOMASZ PIERSCIONEK relishes a collection of cartoons that focus on Palestine from the period 1917 to 1948

PAUL DONOVAN salutes a timely dramatisation of Aneurin Bevin's life, and the political struggle on the left to create the NHS

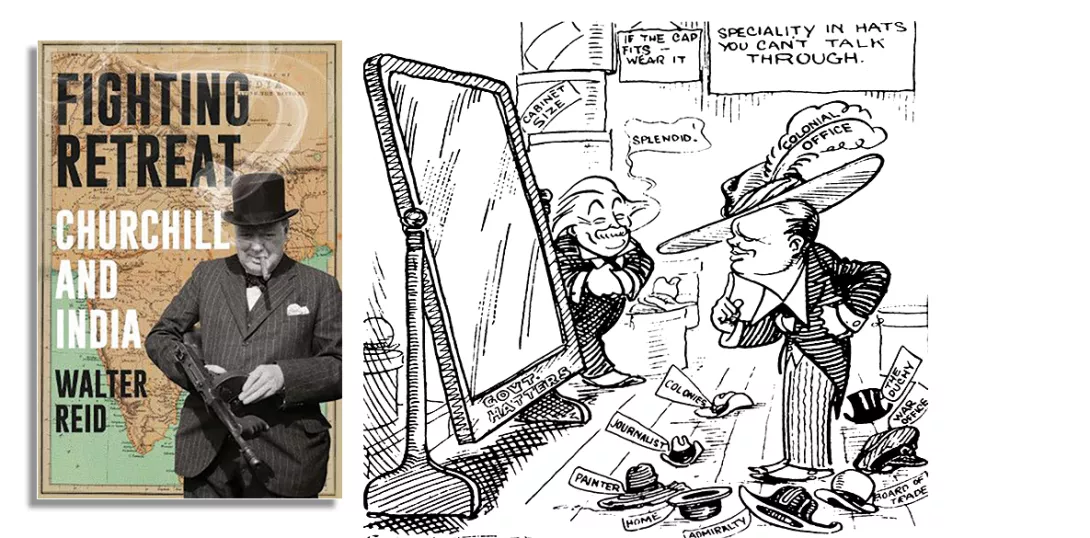

MARJORIE MAYO welcomes a balanced assessment of Churchill’s imperialism that condemns both his language and actions as racist to the core