GORDON PARSONS applauds a marvellous story of human ingenuity and youthful determination, well served by a large and talented company

MICHAL BONCZA welcomes a new version of a classic of British working class literature that should be placed on every school English syllabus

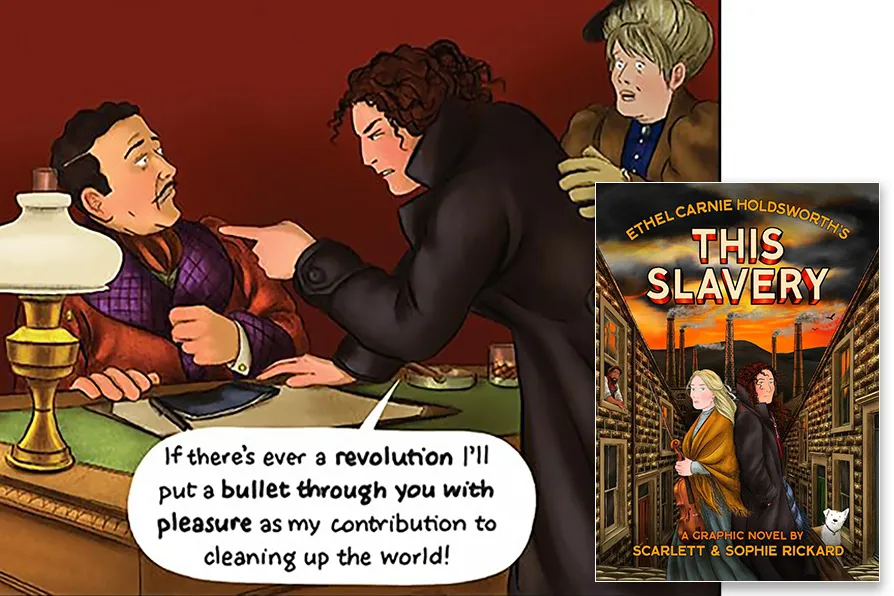

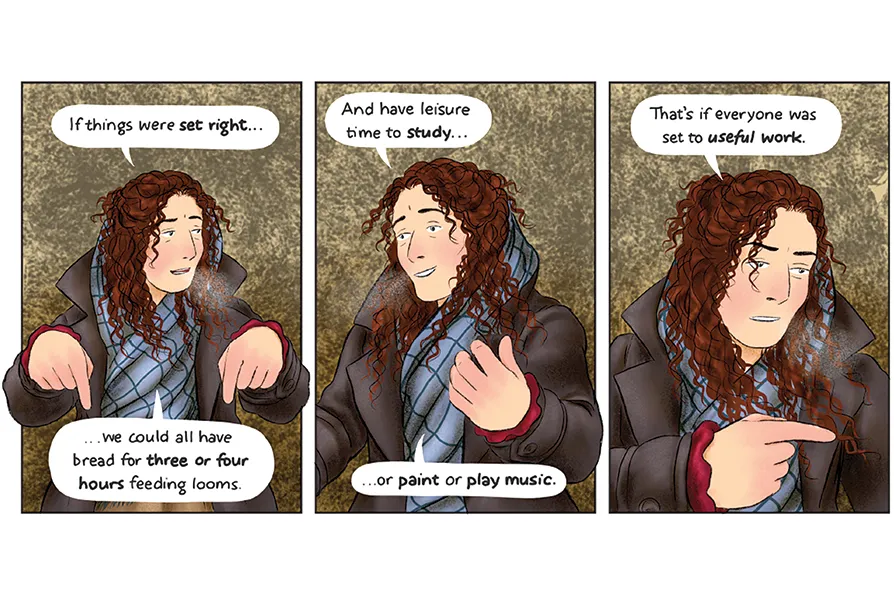

THAT'S THE ATTITUDE: A scene from Ethel Holdsworth's classic, This Slavery[Pic: Scarlett and Sophie Rickard/Courtesy of Selfmadehero]

THAT'S THE ATTITUDE: A scene from Ethel Holdsworth's classic, This Slavery[Pic: Scarlett and Sophie Rickard/Courtesy of Selfmadehero]

This Slavery

by Ethel Carnie Holdsworth, graphic novel by Scarlett and Sophie Rickard

SelfMadeHero £18.99

ETHEL CARNIE HOLDSWORTH a native of Lancashire, was the first working-class woman in Britain to publish a novel. Miss Nobody (1913 and still in print) tells the story of Carrie Brown, who progresses from working in a scullery to owning an oyster shop in Ardwick, Manchester.

Holdsworth, a feminist and socialist, also taught creative writing at the short-lived Bebel House Women’s College and Socialist Education Centre in London (1913-14). The college was named after August Bebel, who wrote the influential text Woman Under Socialism and co-founded (with Wilhelm Liebknecht and Ferdinand Lassalle) the Social Democratic Party of Germany.

This Slavery (1925, and still in print) is her best-known work, and it looks at the lives of sisters Rachel and Hester Martin after the cotton-mill that employs them burns to the ground, quite possibly in an insurance scam.

The just-about-making-ends-meet sisters, with a mother whose health has been damaged by a lifetime spent at the looms, who face — like much of the town’s unemployed population — poverty and precarious survival in the harsh world of pre-war industrial Britain.

The novel is an allegory as well as a Marxist dissection of the class and gender barriers that shaped the lives of women at the time. Naturally, slavery in this context refers, principally, to sexual and wage slavery in capitalism, patriarchal by definition and practice.

After refusing marriage to a fellow weaver, who subsequently emigrates to the United States, Hester decides to marry one Mr Sanderson, a social climber who comes to own a mill: “I’ve reduced my slavery from being a slave of many to being a slave of one,” she deludes herself.

Meanwhile, Rachel agitates against the burned mill’s owner, Mr Barstock, being selected as the local parliamentary candidate: “And when you send him to Parliament to speak for you, you further enslave yourselves.” The meeting ends in the sacking of a food store by the starving jobless and Rachel is sent to prison accused of instigation.

The compelling storytelling is of truly epic proportions although it takes place, nominally, in Great Harwood, near Blackburn, a place of just over 12,000 souls.

Holdsworth lays bare, with impressive skill, the nature of capitalist exploitation secured by an obliging police force and the deviousness of the mill owners, prepared to bring in scabs at a moment’s notice, and/or blackmail, and to besmirch militant workers.

She “weaves” the political and the personal with admirable dexterity, advancing her central goal of feminist class education through the travails of her political alter ego, of the indomitable Rachel Martin.

The book is simply unputdownable as Holdsworth steadily intensifies the Marxist-feminist arguments to instill confidence in the workers, to resist oppression, and thereby to attain a measure of self-respect and dignity and with it the corresponding living wages.

It is perhaps fitting that the novel is reimagined by another set of sisters Scarlett (the illustrator) and Sophie (the writer) Rickard, natives of Folkestone. The sisters have enjoyed great success with their adaptation of the seminal socialist novel, Robert Tressell’s The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists, and No Surrender by suffragette Constance Maud (both published by SelfMadeHero).

As is the norm with the Rickards it is the finesse of the drawn detail, the colour, frame composition and lighting that absorb and nail the narrative beguilingly. Intriguingly, the sun never shines in this wintery Lancashire townscape and poorly lit interiors, all of which is spellbindingly drawn, compounding the darkness of times that descended upon Great Harwood and its poorest inhabitants.

This voluminous opus is a triumph and, unequivocally, a constituent component of British working-class literary legacy that educates and edifies in equal measure, and its place is as much in school English syllabus as in public libraries and progressive households throughout the land.