STEPHANIE DENNISON and ALFREDO LUIZ DE OLIVEIRA SUPPIA explain the political context of The Secret Agent, a gripping thriller that reminds us why academic freedom needs protecting

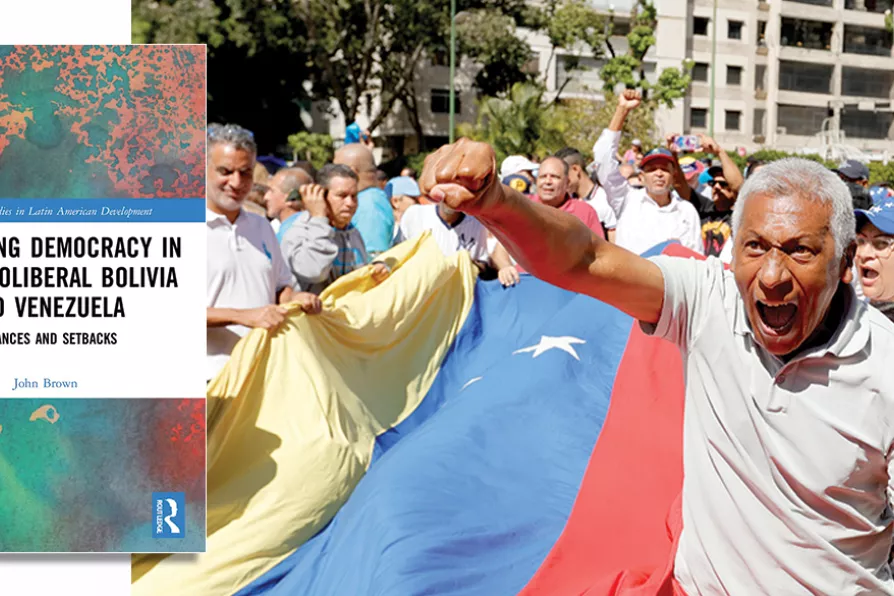

RECALCITRANT CONSERVATIVE ELITES: Supporters of opposition presidential hopeful Maria Corina Machado in Caracas, Venezuela, last week

RECALCITRANT CONSERVATIVE ELITES: Supporters of opposition presidential hopeful Maria Corina Machado in Caracas, Venezuela, last week

IN A brilliant reassessment of the challenges posed to liberal democracy by the radical governments that came to power in Bolivia and Venezuela, scholar John Brown makes an incisive observation.

His book, Deepening Democracy in Post-Neoliberal Bolivia and Venezuela (Routledge, £130), examines the democratic gains enjoyed by hitherto excluded popular sectors under the anti-system outsiders Evo Morales and Hugo Chavez.

Nonetheless, their authoritarian reflexes comprising a form of “illiberal de-democratisation” vexed observers — not least the Anglo-American scholarly establishment — who had bought into a particular species of democracy under neoliberalism as the “only game in town.”

Looking for moral co-ordinates after a tough year for rational political thinking and shared human morality

Looking for moral co-ordinates after a tough year for rational political thinking and shared human morality

Far-right forces are rising across Latin America and the Caribbean, armed with a common agenda of anti-communism, the culture war, and neoliberal economics, writes VIJAY PRASHAD

SETH SANDRONSKY savours a personal account of the life and thought of the great Italian revolutionary