ALAN McGUIRE welcomes the complete poems of Seamus Heaney for the unmistakeable memory of colonialism that they carry

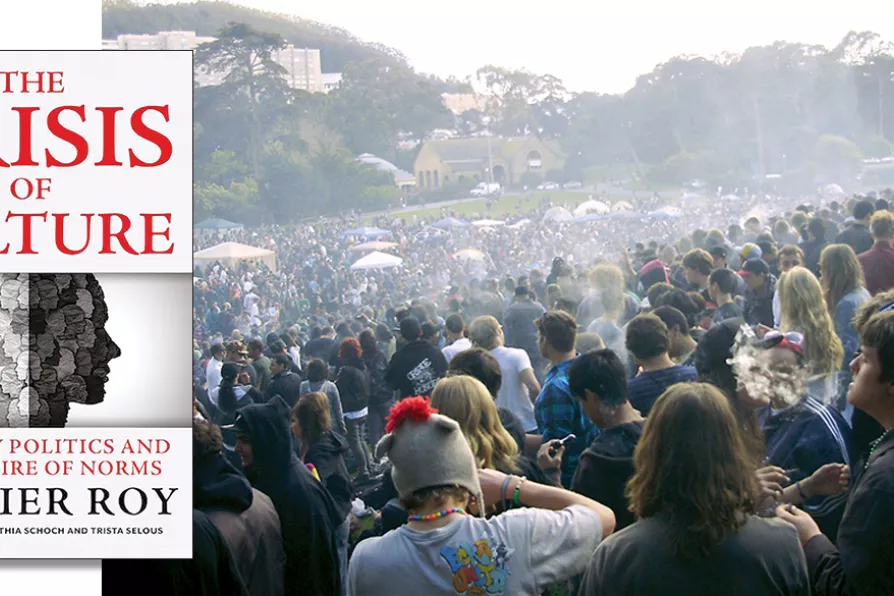

SHORT-LIVED AUTONOMY: Thousands of hippies gather on ‘Hippy Hill’ in Golden Gate Park, San Francisco, April 2010

[Dan Schooling/SanctusAbMortis/CC]

SHORT-LIVED AUTONOMY: Thousands of hippies gather on ‘Hippy Hill’ in Golden Gate Park, San Francisco, April 2010

[Dan Schooling/SanctusAbMortis/CC]

The Crisis of Culture: Identity Politics and the Empire of Norms

Olivier Roy, translated by Cynthia Schoch and Trista Selous

Hurst, £20

IN 1992 when the New Right’s neoliberal revolution was still in full flood, the Marxist thinker Terry Eagleton wrote an essay in which, with great prescience, he foretold a crisis of contemporary culture.

Taking the English literary canon as an example, he argued that right-wing intellectuals were turning literary theory — and by extension the canons of high culture — into an arena of intensive political contestation.

Eagleton wrote: “It is no doubt for this reason that the infighting over something as apparently abstruse as literary theory has been so symptomatically virulent; for what we are really speaking of here is the death of civilisation as we know it.

GAVIN O’TOOLE welcomes, and recommends a a candid, evidence-based record of Britain’s role in the slaughter visited by Israel upon the Palestinians

ALAN McGUIRE welcomes a biography of the French semiologist and philosopher