ALISTAIR FINDLAY recommends the simple cadence, common prose, free verse, and descriptive power of a new collection by Julie McNeill

Throwing stones in glass houses

GAVIN O’TOOLE observes that the call for a new international framework for conflict mediation is fatally marred by a partisan position on the Isreali-Gazan conflict

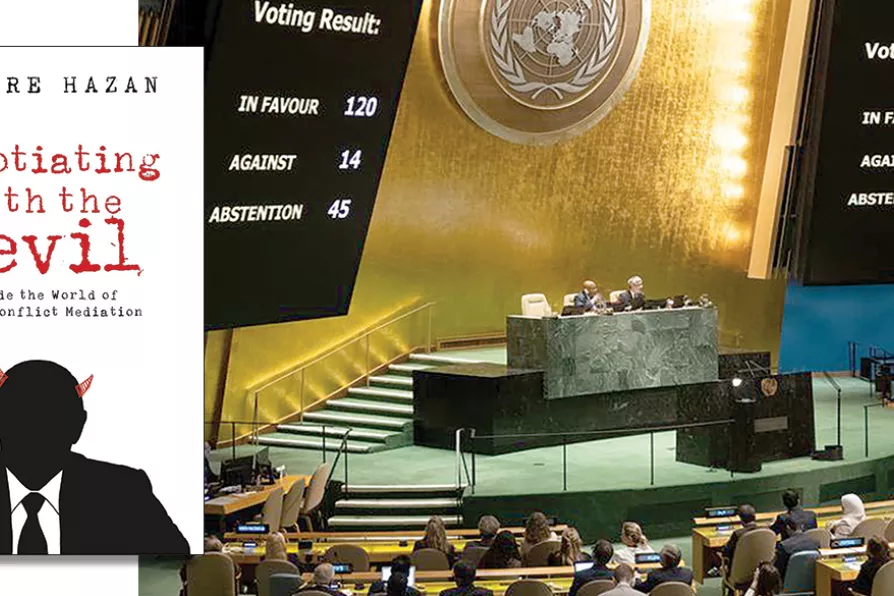

PLACE OF DISCORD: The UN General Assembly has adopted, on October 26 2023, a resolution calling for an “immediate, durable and sustained humanitarian truce” between Israeli forces and Hamas militants in Gaza and demands a “continuous, sufficient and unhindered” provision of lifesaving supplies and services for civilians trapped inside the enclave

[UN Photo/Evan Schneider]

PLACE OF DISCORD: The UN General Assembly has adopted, on October 26 2023, a resolution calling for an “immediate, durable and sustained humanitarian truce” between Israeli forces and Hamas militants in Gaza and demands a “continuous, sufficient and unhindered” provision of lifesaving supplies and services for civilians trapped inside the enclave

[UN Photo/Evan Schneider]

Negotiating with the Devil: Inside the World of Armed Conflict Mediation

Pierre Hazan

Hurst, £18.99

IN 1929 from his fascist cell, Antonio Gramsci described epochal changes as Europe tore itself apart — an old world was dying and a new one was struggling to be born.

It was “a time of monsters,” the Italian Marxist warned, with chilling prescience.

Pierre Hazan uses this metaphor to situate the key dilemmas facing conflict mediators today in a similarly dark landscape in order to ask how they are to fulfil their role in a deeply divided multipolar world where the very idea of an “international community” is redundant.

Similar stories

GAVIN O’TOOLE welcomes, and recommends a a candid, evidence-based record of Britain’s role in the slaughter visited by Israel upon the Palestinians

As Israel breaks ceasefire with air strikes on Gaza, killing 400, and ministers backtrack on acknowledging Israeli war crimes, campaigners ask ‘how many more Palestinians will be slaughtered before Britain stops sending arms to Israel?’

Israel follows through on threat to cut off electricity supply to the Palestinians in Gaza