TONY BURKE speaks to Gambian kora player SUNTOU SUSSO

Central questions unanswered

ALEX HALL is impressed by the scholarship of the book but disappointed by its failure to explore in significant depth the ‘why’ of the Gaza predicament

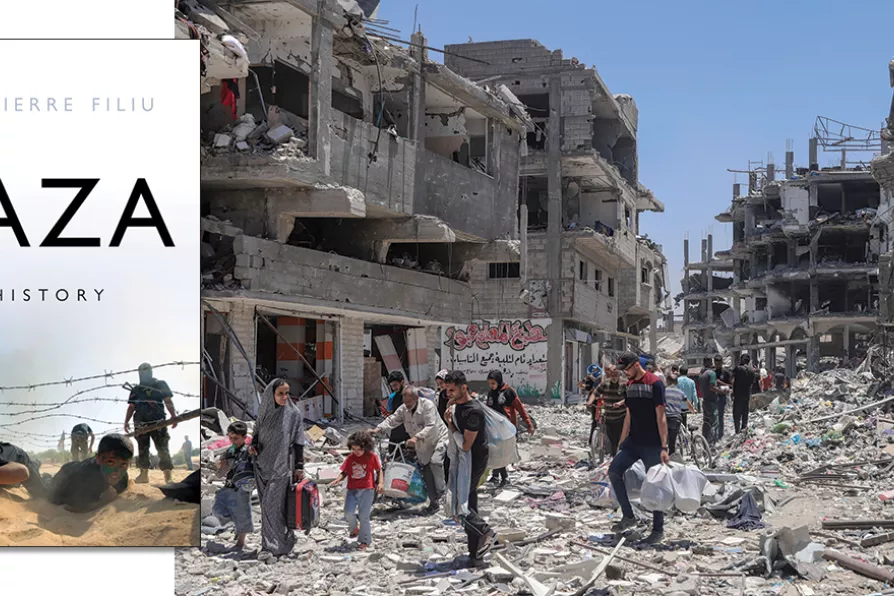

MASS EXODUS: Palestinians leave through the destruction in the wake of an Israeli air and ground offensive in Jebaliya, northern Gaza Strip

MASS EXODUS: Palestinians leave through the destruction in the wake of an Israeli air and ground offensive in Jebaliya, northern Gaza Strip

Gaza, A History

by Jean-Pierre Filiu

Hurst, £18.99

JEAN PIERRE FILIU was a career diplomat representing France in Jordan, Syria and Tunisia and later held various advisory roles in the French government.

In 2006 he joined Sciences Po as a professor of Middle East studies.

This is the second edition of Filiu’s book. It won the 2015 Palestine Book Award and covers Gaza from 1500 BC to 2012. It has been updated with an additional 20-page afterword penned in March 2024.

Similar stories

Israel’s messianic settler regime has moved beyond military containment to mass ethnic cleansing, making any two-state solution based on differential rights impossible — we must support the Palestinian demand for decolonisation, writes HUGH LANNING

RAMZY BAROUD on how Israel’s narrative collides with military failure

ALEX HALL is intrigued by a detailed history of Gaza that demonstrates its historic resilience and changing economy