MARIA DUARTE and ANDY HEDGECOCK review The Tasters, A Pale View of Hills, How To Make a Killing, and Reminders of Him

JONATHAN TAYLOR is intrigued how good storytelling can make a hobby as obsessional as metal detecting seem fascinating

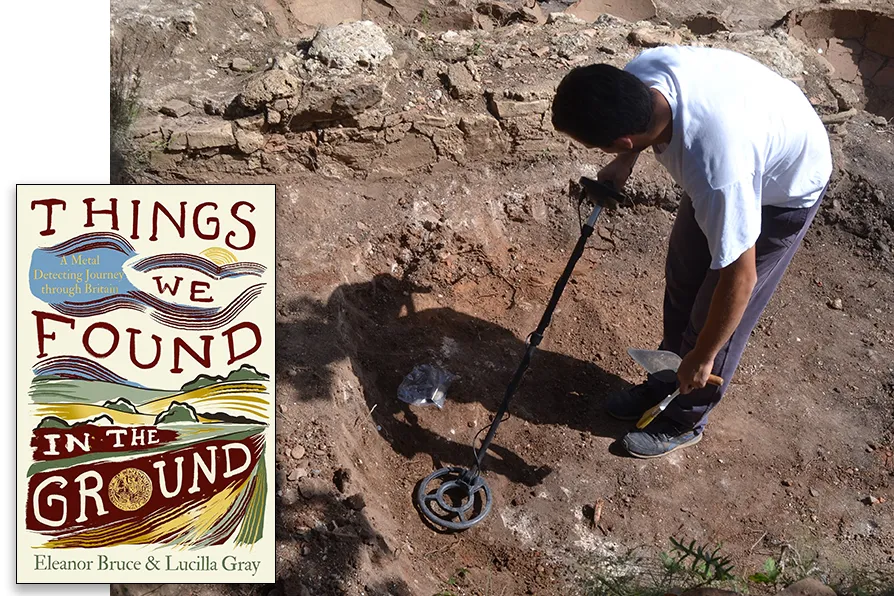

THE STORY BEGINS: A metal detector in use at an archeological site. [Pic: Zalfija/CC]

THE STORY BEGINS: A metal detector in use at an archeological site. [Pic: Zalfija/CC]

Things We Found in the Ground: A Metal Detecting Journey through Britain

Eleanor Bruce & Lucilla Gray, HarperNorth, £20

IN his book about autism and special interests, What I Want To Talk About, Pete Wharmby writes: “Ever since I was a child, I desperately wanted others to be as interested in my interests as I was,” but “it hardly ever happened … We often go through life believing no-one cares enough about what we really want to talk about.”

It’s a familiar feeling: one person’s special interest in Lego is another’s idea of death-by-boredom; one person’s trainspotting compulsion is another’s bewildered: “You do what all weekend?” Explaining obsessional hobbies to the uninitiated can have a similar effect to narrating a dream to an uninterested family member over breakfast.

So the challenge of communicating the joys of metal detecting, in a form which is neither a “how-to” guide for beginners, nor a compendium for detectorist-cognoscenti can’t be over-stated. Yet this is the aim of Things We Found in the Ground by Eleanor Bruce and Lucilla Gray: to reach beyond the detecting community to a more general readership, many of whom (myself included) are unlikely ever to start digging up a nearby field; and to persuade us that there is more to it than “a hobby exclusively, as it is stereotypically seen, for the middle-aged man escaping the clutches of his wife.”

The authors achieve this primarily through an innovative intermixture of narrative forms and genres. The book moves between memoir, personal anecdote, historical exposition, and even, at times, a kind of immersive historical fiction, focusing in on moments related to particular found objects – “allowing [us]… to escape for a moment into somebody else’s story.”

To tell all these different kinds of stories, the book also flits between narrative perspectives (first-person, third-person, first-person-plural), and tenses (past and present). Sometimes, this can be disorientating, jarring – but, for the most part, it means that the book is lively, unpredictable, maintaining the reader’s interest in a way that a more monovocal approach might have alienated non-detectorists.

In part, this flexible approach to storytelling arises from the varied nature of the found objects themselves: each unearthed coin, ceramic shard, badge, buckle and axe has its own individual micro-story – which is, in turn, connected with a macro-story from its wider historical context, whether neolithic, Roman, Anglo-Saxon, Medieval, Tudor, Victorian, or modern. “It’s never about the age of the finds, their value or even the rarity,” suggest Bruce and Gray – rather:

“It’s the stories pulling us in … These objects … retain their ability to communicate and hold the stories of the lives they’ve touched … It’s the passage of these lives that sees the ground become a great repository of history and memory, harbouring objects … that are … waiting for the perfect moment to reveal themselves.”

Things We Found In The Ground attempts to encompass all of these different kinds of stories: it tells of the histories and memories associated with the found objects, the possible “lives they’ve touched,” as well as the “perfect moments” when the objects finally reveal themselves to the author-detectorists.

As regards the latter, what the authors understand is that the search-and-find quest of the detectorist has an in-built narrative structure to it. Many of the contemporary sections of the book (perhaps, on balance, slightly too many) chart this narrative: from searching, to initial disappointment, to a “perfect moment” of revelatory discovery, where something strange, with its own story, is unearthed. This is “the art of searching” in two senses: the literal one of metal detection, and the aesthetic one of storytelling, such that the reader starts to share the epiphanic pleasure of discovery with the detectorists.

It would seem that it’s all about how you talk about your special interests, rather than what they are in themselves: good storytelling can make any obsessional hobby – metal-detecting, trainspotting, or Lego – seem fascinating to the uninitiated.

Jonathan Taylor is an author, editor, lecturer and critic. His most recent book is A Physical Education: On Bullying, Discipline & Other Lessons (Goldsmiths, 2025). He directs the MA in creative writing at the University of Leicester.