Tyrannosaurs in Thailand, colonialism as videogame, and a feminist gem from 1936

ALAN MORRISON recommends an outstanding and timely anthology of poems that reflect the experience and consequences of African migration

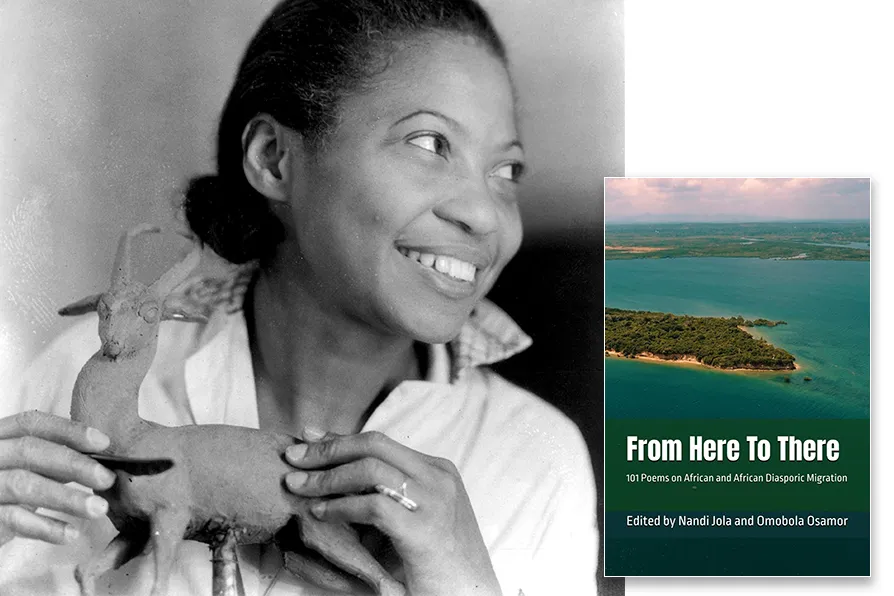

INSPIRED: American sculptress Augusta Savage [Pic: Public Domain]

INSPIRED: American sculptress Augusta Savage [Pic: Public Domain]

From Here To There – 101 Poems on African and African Diasporic Migration

Edited by Nandi Jola and Omobola Osamor, CivicLeicester, £9.99

AT this time of anti-immigrant rhetoric and measures of the Western right, from Trump’s thuggish trigger-happy ICE raids in the US to the rise of Reform, “asylum hotel” protests, and the “Raise the Colours” campaigns and rallies in Britain, the Africa Migration Report Poetry Anthology Series could not have come at a more important time.

From Here To There — 101 Poems on African and African Diasporic Migration brings together 63 poets from across Africa: Cameroon, Eritrea, Kenya, Morocco, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, South Africa, Uganda and Zimbabwe — as well as poets in Britain, the US and Europe of African descent. The title has an echo of Ian Sanjay Patel’s We’re Here Because You Were There (2022) quoted by Zarah Sultana at the close of her rousing speech at the first Your Party conference.

The poems are as diverse in style as the diasporic experiences they express, with themes ranging from departure, transit, destination, to attempts at integration and discrimination.

Thulani Mahlangus Where I Am From expresses ancestral dislocation: “My grandparents are shadows in photographs,/ Their names stitched in whispers./ I carry their absence like inheritance./ Migration is the ghost story of my blood.”

Nandi Jola lays out a race schism in historical association: “Your nostalgia and mine are two different things/ if you remember the Beatles/ I remember Emmett Till” (an African-American boy lynched in 1955 Mississippi).

In Black Women she recounts black women pioneers languishing in a shadow-history: Mary Maynard Daly (the first black US woman to earn a chemistry PhD), Augusta Savage (a sculptor of the Harlem Renaissance) and Harriet Tubman (an abolitionist). That I had to Google the first two attests to the poem’s point.

Octavia McBride-Ahebees 1822/2014 depicts free black man Denmark Vesey’s attempt to lead a slave revolt in 1822 Carolina.

M Chamber’s African Exile transfigures an imported fertility statue as a maquette of an African slave: “Shipped like a commodity,/ put up for sale,/ auctioned off as property.”

Jenny Mitchell’s Looking at the Benin Bronzes is hauntingly elliptical: “Grow your mouth./ Say what I want you to hear./ But above me a flag…/ And behind you those flowers and leaves./ A church in the shape of your head.”

Nasra Dahir Mohamed sculpts the motto: “I am Somali, moving is in my blood —/ A nomad.”

Victor Ola-Matthew’s Another Man’s Land emphasises the refugee’s lot: “Busy securing your future, chasing a permanent residency.”

In There Will Always Be One More Thing Ambrose Musyiwa puts strikethroughs across racial descriptors to emphasise unspoken European prioritisation of white Christian Ukrainians over black and brown African and Asian refugees. His St Georges Walks Into A Pub riffs on racist tropes: “st georges,/ does lynch mobs/ strange fruit/ swinging off southern trees?/ strange fish/ off small boats?” As does Dike Nwosu’s rap-like A Journey Full Circle: “Biafra, Nigeria./ History, hysteria/ Lonely London./ No blacks, no Irish and no dogs./ Throw in the towel, Enoch Powell./ Rivers of blood.”

Two poems satirise anti-immigrant rhetoric: Jana van Niekerks From God to Dust: “I am a Parvenu/ I live on charity/ I renounce my individuality”; and Joseph C Ogbonna’s Dont Surprise Me Europe: “I am Africa,/ colonial Europe’s partitioned cake/ ancestral habitat of the/ itinerant welfare seeker,/ to have my needs sated in lands west of Bosporus.”

Frank Olunga satirises racial profiling: “When I go shopping. They give me free security./ Someone to watch what I buy. My skin, the issue.”

Skin, not simply in terms of pigment, is a common motif. In Philisiwe Twijnstra’s Zulu Girl In Rotterdam: “In the sea of whiteness, the body floats. Drifts in foreign land./ The city whispers she’s black/ The black forgotten body is bruised”; in Furaha Youngblood’s Adrift: “The dressing table holds round powder boxes filled/ with shades that complement only cream and ivory skin tones./ Ebony, Chocolate, Cinnamon, and Caramel are foreign”; and in Fauziyatu Moro’s Echoes Of A Migrants Ritual: “Blisters,/ Birthed from the stinging union of skin and cashew bark/ The skin map on her aged arm will be the identity charm.”

Deborah Saki’s A New City laments the West’s pharmaceutical dystopia: “We did not leave for the flat white pills in their transparent orange tubes.”

Dike Okoro’s Remembering recounts the Nigerian civil war: “Bombs ripped/ apart thatched houses. Bible clutched”; and in Patrick Kapuya Tshiuma’s Until Again Goma Is Free!: “Bombs dropped while flowers blossomed.”

The Yoruba slang term Japa (to leave ones country for better opportunities) crops up in many poems.

From Here To There is a vital verse intervention amid the toxic discourse surrounding immigration to the West from past European colonies, powerfully emphasising the humanitarian and karmic momentum that propels it. It is essential reading not simply for such messages, but for the ripe poetries that carry them on rafts of buoyant afflatus.