Tyrannosaurs in Thailand, colonialism as videogame, and a feminist gem from 1936

ROGER McKENZIE recommends a landmark study of black journalism in Britain that is a wake-up call to prioritise working-class struggles, where black people are recognised as an important part of the class

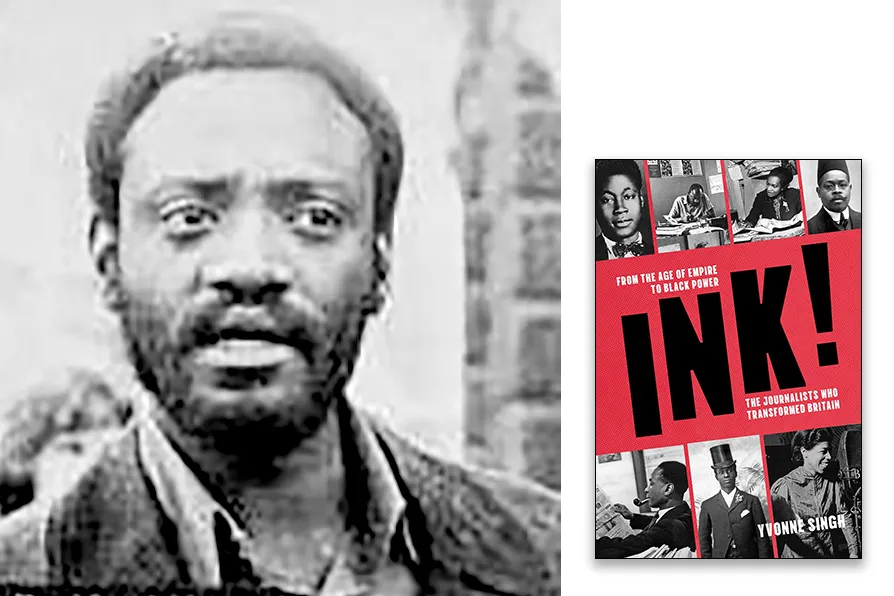

Leighton Rhett Radford "Darcus" Howe was a British broadcaster, writer, and racial justice campaigner. This image comes from a poster in support of The Mangrove Nine, of which he was one. [Pic: The National Archives UK/CC]

Leighton Rhett Radford "Darcus" Howe was a British broadcaster, writer, and racial justice campaigner. This image comes from a poster in support of The Mangrove Nine, of which he was one. [Pic: The National Archives UK/CC]

INK!: From the Age of Empire to Black Power, the Journalists who Transformed Britain

Yvonne Singh

The History Press, £22

ANY book that reminds the world of the importance of revolutionary black activist and journalist Darcus Howe is always going to go down well with me.

What makes Ink!: From the age of Empire to Black Power — The Journalists who Transformed Britain by Yvonne Singh, so important is that it outlines the “intellectual scaffold” for black power that came from earlier decades. It underlines the point that black political activity in Britain flourished way before the usually cited 1960s.

As well as highlighting the importance of Howe to black political activity in Britain, it also makes clear the significant contribution made by other remarkable black journalists — Samuel Jules Celestine Edwards, Duse Mohammed Ali, Claude McKay, George Padmore, Una Marson and the legendary Claudia Jones. In reality each of these formidable characters could carry the moniker “legend” with ease for the contributions they have made to black activism as well as their journalism.

Singh is thought-provoking. She asks: if newspapers are, as they are often described, the “first rough draft of history,” then what does this mean “when your history is not deemed worthy of preservation?” I would add, what does it mean when newspapers are ignoring, ridiculing or dehumanising black lives?

Each of the subjects of this book answer this in their own way, and in relation to the era in which they operated.

But this important question only served to underline for me how important it is to see the existence of black journalists as not a matter of aesthetics or a diversity numbers game. It is instead a matter of challenging the racism that says black journalists are only capable of writing about “black matters.”

Each of the subjects obviously talked about and challenged the racism they faced — it would be rather odd if they didn’t. But they also related their lives, and what they saw happening around them, to the material circumstances facing the entire working class.

This was particularly the case for McKay, Padmore and Jones, all, at varying points, communists. All advocated for the importance of class unity between blacks and whites.

I began this review by highlighting the importance of Howe. This is partly because he is of the generation that provided a spark for my own activity. But it is also because he is the only one of the subjects I actually met and got to engage with.

We didn’t always agree. After all, we were from different generations, with different backgrounds and experiences, but I believe he was a force of nature with a fierce intellect who understood the importance of linking theory to action.

Howe was also one of the few Caribbean/British political figures I can remember appearing on television during the early 1980s. The Bandung Files, that he hosted with Tariq Ali, and later The Devil’s Advocate that he did solo were essential viewing.

Each of the seven journalists discussed by Singh, in their own way, also married theory and activism with the tools available to them in their respective eras.

Singh, herself once a journalist and now a lecturer, has provided us with an important book which I recommend as a gateway for an exploration of the primary writings of these excellent journalists. Each of them made it possible for me and other black people to even consider this largely white profession as something we could do.

But it’s actually much more than that. The gift that Singh has provided for us in this book is how these black journalists — some largely forgotten — were at the forefront of smashing the phoney notion that there is some sort of balance to be achieved in journalism. Those that lay claim to this non-existent even-handedness have been perfectly happy to write black and working-class struggles out of history and from their coverage of what is currently happening in the world.

These magnificent seven were clear that our stories of struggle must be foregrounded and told in an unapologetic way. It would be wrong to see these as seven biographies linked only by the colour of their skin or the racism each witnessed or faced.

Singh has provided a wake-up call for all journalists to prioritise working-class struggles and that black people are an important part of the class.