[[{"fid":"60604","view_mode":"inlineleft","fields":{"format":"inlineleft","field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]":false,"field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]":false},"link_text":null,"type":"media","field_deltas":{"3":{"format":"inlineleft","field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]":false,"field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]":false}},"attributes":{"class":"media-element file-inlineleft","data-delta":"3"}}]]THE slogan of the International Workers applies not just to May Day but to all workers and progressive left movements in struggle all year round regarding peace, gender equality, anti-racism, anti-sectarianism, the environment, human rights and the abolition of poverty.

No better way to start the year than with some Thursday poems emblematic of that slogan which feature poems on Palestine and Bloody Sunday, and today reviewing a new centenary collection of poems dedicated to John MacLean, Now’s The Day, Now’s The Hour, a theme also featured in the Morning Star on November 30 2023.

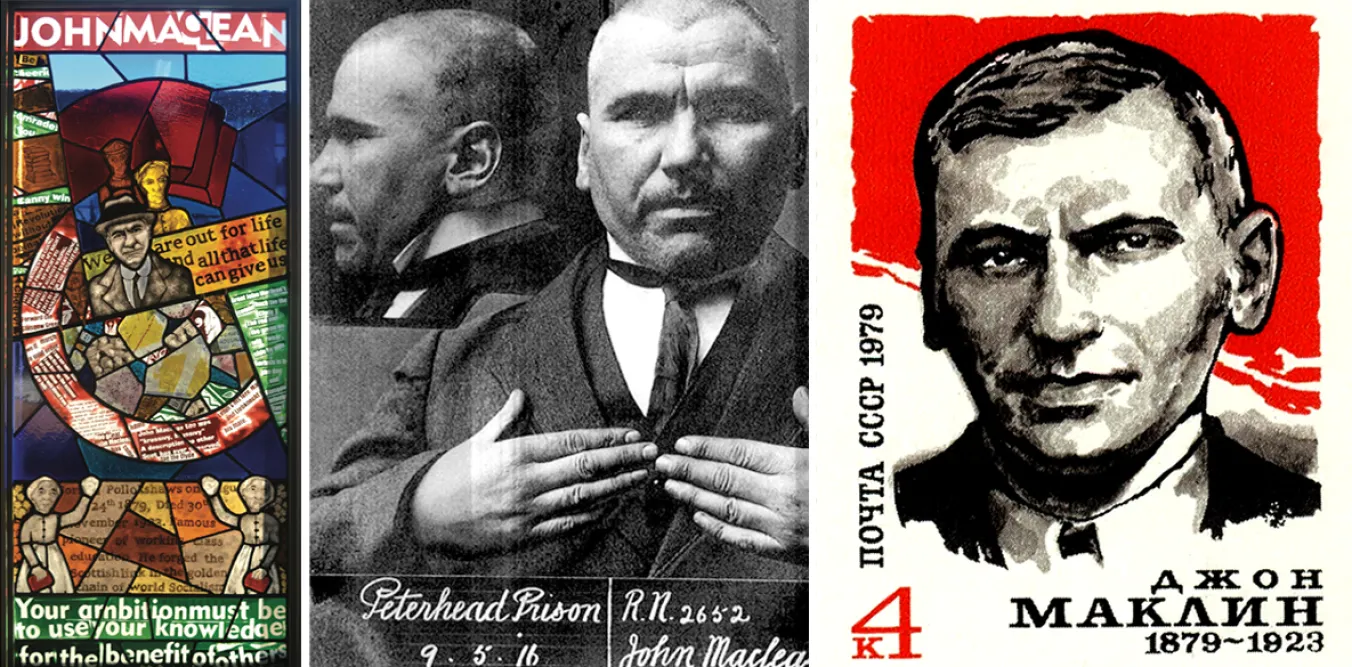

Maclean was a Red Clydesider who, like Lenin, resolutely denounced the Great War as an imperialist conflict and one that workers in all countries should refuse to fight or die for, which led to MacLean’s long imprisonment, harsh forced-feeding and an early death aged 53 in 1923.

He was a teacher and Marxist educator — not the theorist that James Connolly is now seen as, nor the leading industrial organiser of the British Communist Party William Gallacher helped found in 1920 and which the bulk of Scottish Marxist activists joined in preference to the Scottish Socialist Republican Party advocated by MacLean.

It might be noted that MacLean continued to call himself a communist and stood for election as a Bolshevik even after this in the 1922 election.

MacLean’s actual legacy was to lay the foundations in Scotland for independent working-class education and to influence a new generation of labour leaders and activists in Marxist economics classes, including Gallacher. “Outside of left-wing Scottish nationalist groups,” writes William Knox in Scottish Labour Leaders, “MacLean’s importance is more symbolic than intellectual or political; the result of his persecution rather than his writings or ideas.”

MacLean also attracted a literary following that has lasted from 1920 to the present day, first promoted by Hugh MacDiarmid through the Scottish Literary Renaissance (founded in the same year as the Communist Party of Great Britain) which gave him credence with the radical wing of the Scottish independence movement, and indeed most of those, like MacLean, MacDiarmid and the majority of poets and songsmiths in this collection, dead or alive, who never had any truck with the petty bourgeois braveheart nationalism on offer from the current SNP.

The collection mixes poems written by Scottish poets and songsmiths of the Hugh MacDiarmid, Hamish Henderson, Sorley MacLean and Thurso Berwick generation with excerpts from MacLean’s speeches and writings. This older body of texts often tend towards a “come-all-ye” poetry and folksong tradition which contains some great if familiar stuff, including classics like MacDiarmid’s Krassivy, Hamish Henderson’s Freedom Come All Ye, and Sorley MacLean’s Clan MacLean, although I found too many of the later poets following this celebratory theme too laboriously.

Those who do try to break what Ezra Pound called “the new wood” — and many of them not all that young either — give full value for money, well worth the tenner required, including some poems I’m still scratching my head over, and some spinning off at tangents linked more to the era than The Man in Peterhead of John S Clarke.

That period poem is more than worth a mention as Clarke knew MacLean, and fluently deploys the rhythms and rhyme scheme of Kipling’s empire loyalist If to good effect in the closing lines: “Then, toilers, for your own sake up and liberate MacLean/You could do it – aye, tomorrow – if you dared!”

Standout poems for me include Alan Riach’s The Line of John MacLean, David Betteridge’s Jaggily, Jackie Kaye’s three-pager When Paul Robeson Came Back to Glasgow and Alec Finlay’s very fine After Spicer, After Lorca (which should also perhaps have credited “After William Carlos Williams”).

There are also absences in this collection for me: no details of the poets given, old or new; no mention of William Gallacher, except critically in the foreword, and in the poem MacDiarmid wrote celebrating his 80th birthday in which he calls him “a sprig of white heather in the future’s lapel.” In the notes to this poem it is asserted that the only revolutionary figure to stand comparison with MacLean (whom MacDiarmid had compared to Burns and Lenin in Krassivy) was Gallacher.

I can however rectify a third absence by choosing for today a poem that should have been included but wasn’t: Yet Another Poem About John MacLean (from Colours of Grief, Shoestring Press, 2002), written by the Scottish poet Angus Calder, the radical historian, MacDiarmid scholar, pal of Hamish Henderson and first convener of the Scottish Poetry Library.

Angus also voted for the Scottish Socialist Party when the Scottish Parliament opened its doors in 1999 which I, a popular front communist like Gallacher, had campaigned for along with the party since 1989, unlike the SNP and the Tories, but which has served to save both of their bacons from political oblivion.

Now’s the Day, Now’s the Hour is edited by Henry Bell & Joey Simmons, and published by Tapsalteerie, £10