GEOFF BOTTOMS applauds a version set amid the violent conflicts of the 19th century west African Oyo empire before the intervention of British colonialism

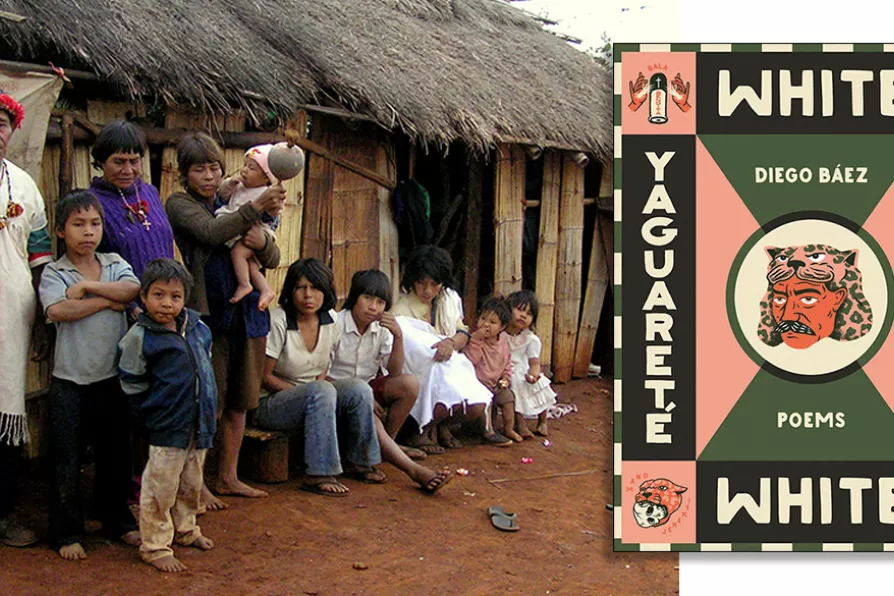

Pai Tavytera Indians, part of the Panambi'y tribe in Amambay, Paraguay. Pai Tavytera is an arbitrary name given to northern Guarani people of eastern Paraguay

[FrankOWeaver/CC]

Pai Tavytera Indians, part of the Panambi'y tribe in Amambay, Paraguay. Pai Tavytera is an arbitrary name given to northern Guarani people of eastern Paraguay

[FrankOWeaver/CC]

IN Guarani mythology, an almost mystical creature named Yaguarete-aba (“jaguar man”) can transform into a werewolf-like creature using jaguar skin, incense and chicken feathers to speak with the gods. There is also “acygua,” the jaguar part of the person, representing the Other of the gods and the human desire for immortality.

Jaguars, once a vibrant part of Paraguay’s cultural, religious and natural landscape, are now facing the threat of extinction, primarily due to human hunting and the rapid destruction of their natural habitat.

Despite the dwindling numbers of jaguars in South America, their symbolic power resonates in numerous stories and folktales from Paraguay and beyond. In Yaguarete White (University of Arizona Press, £19), Latinx poet Diego Baez evokes Guarani mythology through personal narratives and migrant experiences, skillfully woven a tapestry of cultural appreciation and diasporic resonances.

Peter Mitchell's photography reveals a poetic relationship with Leeds