SCOTT ALSWORTH suggests that video games have a lot to learn the rich tradition of Marxist theatre

ALAN MORRISON guides us through the richly descriptive and accessible poetry of a notable British-Irish poet

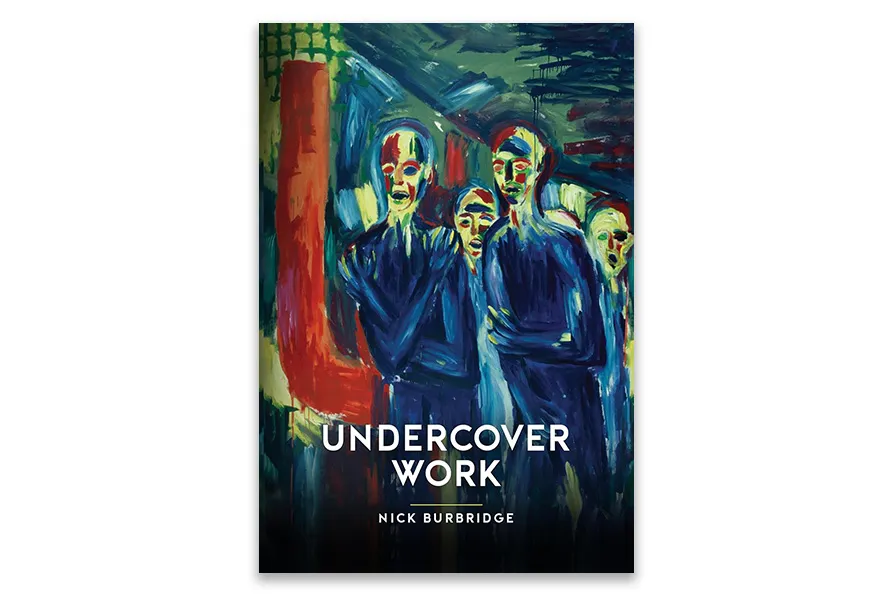

Undercover Work

Nick Burbridge, Olympia, £8.99

NICK BURBRIDGE is a Brighton-based folk songwriter for McDermott’s Two Hours, and The Levellers, and is also a widely published poet and writer, author of novels, plays (Cock Robin) and three previous poetry collections. Undercover Work is his fourth collection and the first in 14 years.

Burbridge’s poetry is well-sculpted, richly descriptive, and accessible, but there is in it a straddling angst and a dark edginess that marks it out as distinct amidst the mainstream.

The continuing narrative of Burbridge’s alter ego Dublin Flynn punctuates the collection, most colourfully in the picaresque Molloy’s Wake, and Flynn And The Ranter: “I should be squatting in some long-lost forest/ plotting mayhem among Diggers, Levellers/ and Anarchists. Call me closet revolutionary,/ my path unfolds in my imagination.”

Burbridge, of Irish roots himself, writes descriptively of his ancestry in Veterans: “I summon doughty forebears…/ that flourished in a cottage and a market garden/ growing courgettes, cauliflowers, and strawberries/ under cloches, in the hills near Bandon,// … where rivalries once took a heavy turn.”

Profiles is a tangible poem: “Barstool, broadsheet, and gin-shot,/ rolling shag smuggled in from France”; “When ghosts return, you still roll in the gutter/ and whoever lifts you hears your bitter tale:/ Belfast battlegrounds that claimed your brothers.”

Dirty Peace is set during The Troubles: “As ageing sprite, forsaking ballot box/ and Armalite shakes hands/ with ermine figurehead, the undercover man/ stands looking back through forty years of rain/ round Portadown at the old Chalet Bar,// a dark shell shut in by corrugated iron/ smelling of slurry and stacked wood.”

This piling of description is typical of Burbridge’s more viscerally charged poems: “It’s too much for the acne-ridden squaddie/ from Carshalton; his cocked finger bends,/ his shoulder jerks at the kick of the butt;/ a salvo pocks the plaster opposite.” This is juxtaposed with the older man’s “volley of hurled prayers to every saint in heaven/ and the Holy Mother” who “left him untouched –/ squatting by his pile with the burnt-out match.”

A passage on a photograph of his father “in light fatigues, marching by an Indian lagoon” during World War II brings to mind Welsh poet Alun Lewis (1915-44) on his doomed Burma campaign, and Burbridge’s style shares some lyrical qualities with the author of Raiders’ Dawn and Ha! Ha! Among the Trumpets.

Burbridge depicts those on society’s margins: addicts, the homeless, and the mentally afflicted: “More stale belch than prophecy./ Too many deaths in the family,/ shots of Southern Comfort,/ dark chemicals at work./ Against the undertow of solitude/ she tried an angry march.”

The clipped phrasing works extremely well. This poem of coastal psychosis is aptly titled Too Far Out, presumably an allusion to Stevie Smith’s iconic lines: “I was much too far out all my life/ And not waving but drowning.”

From Sham To Rock is an intimate poem-portrait of Dublin-raised writer Gabriel Duffy (1942–2008), onetime protege of Colin Wilson, in his obscure Brighton twilight: ”…in your trenchcoat and wool hat/ bustling like a badger in a bolthole:/ three dim rooms that brook no family/ but house a cabin bed, a thousand books,/ desk and screen, where you wrestle/ with impenetrable projects so long shelved.”

The poem’s title is taken from Duffy’s 2003 memoir, his only published book, and in that, a testament to an author’s un-prolific output not dissimilar to Cyril Connolly’s Enemies of Promise (1938). Burbridge’s is a blisteringly honest depiction: ‘Licking your fingers as you fiddle with your fringe,/ lost in a blistering torrent on whatever next,/ while those unyielding works became dead weights/ on your desk, a place of failure, a table/ laid with plates for an uneaten dinner.”

The “uneaten dinner” serves as a metaphor for the writer’s unfulfilled promise.

Burbridge continues: “when… I’m washed up on the black strand/ where all drifters end, let me find you,/ battling your tar-baby with stuck hands,/ as mine, inevitably, waits for me.”

This underbelly of cusp-of-recognition Brighton bohemianism encompasses the self-perceptions of Burbridge and what he terms in the opening poem his “obscure celebrity.”

But this vibrant volume generates its own limelight on a promise fulfilled.