MARJ MAYO recommends a lyrical and disturbing account of the tragic suicide in Venice of Pateh Sabally, a refugee from the Gambia

ANDY HEDGECOCK revels in a hugely enjoyable but deadly serious examination of the 1930s, that is an indictment of our own era

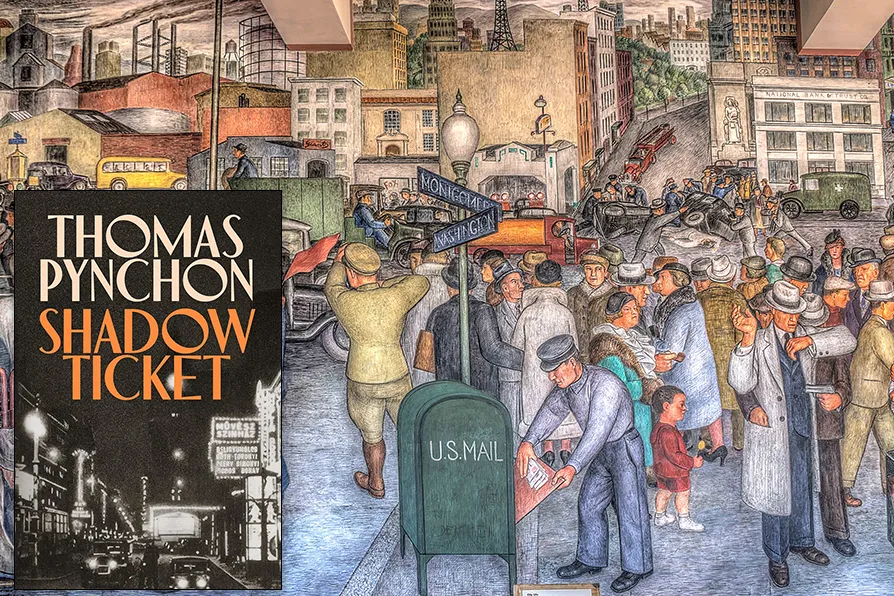

PASQUINADE: Mural in Coit Tower, San Francisco, 1934, by Victor Arnautoff with the help of Edward Hansen and Farwell Taylor. Notice the robbery on the bottom right, and the car accident in the center. [Pic: Public Domain]

PASQUINADE: Mural in Coit Tower, San Francisco, 1934, by Victor Arnautoff with the help of Edward Hansen and Farwell Taylor. Notice the robbery on the bottom right, and the car accident in the center. [Pic: Public Domain]

Shadow Ticket

Thomas Pynchon, Jonathan Cape, £22

IN the late 1970s, critic and academic Edward Mendelson praised Thomas Pynchon’s willingness to delve into aspects of contemporary life ignored by other writers. Pynchon’s work, Mendelson asserted, tackled “realities ignored by the fiction that we have come to accept as realistic.”

At that stage Pynchon had published three encyclopaedic novels exploring US history, culture and politics through a kaleidoscope of genre fiction, absurdist humour, cybernetic theory, philosophical games and linguistic pyrotechnics.

Five decades and six novels later, Pynchon is still writing at the age of 88. His style has evolved but Mendelson’s assessment of his satirical and paranoid imagination is as apposite as ever.

Shadow Ticket begins as a manic and amusing pastiche of the hard-boiled private eye story with musical interludes (there are 16 songs). It’s 1932 and Hicks McTaggart, strike-breaker turned private eye for the Milwaukee office of the Unamalgamated Ops agency, is commissioned to track down missing heiress Daphne Airmont, daughter of Wisconsin’s Al Capone of Cheese. Meanwhile, there’s a gun-running WWI U-boat in the depths of Lake Michigan.

So far, so Sam Spade meets the Mighty Boosh. But this is Pynchon territory, so deeper, more perplexing channels flow beneath the narrative’s glittering surface of wit, erudition and entertainment.

There are compelling insights into US history between the war: the economy is sinking deeper into depression, prohibition is about to be abolished, and the use of violent thugs to attack striking workers is endemic.

Then there are Hicks’s chaotic encounters with controlling individuals and institutions. His affair with torch singer April attracts the unwelcome attention of mob boss Don Peppino, who sends assassins dressed as elves to resolve the matter. He also drifts onto the radar of shadowy state institutions. Federal Agent TP O’Grizbee’s warning that “We haven’t even begun to show how dangerous we can be” has powerful contemporary echoes in the wake of the killings of Renee Nicole Good and Alex Pretti on the streets of Minneapolis.

Pynchon’s historically correct backdrops and counterfactual subplots (which include a coup against Franklin D Roosevelt) conjure a warning for the present. Fascists abound. The roster of homegrown Nazis includes mob bosses, bowling teams and people in positions of civic power.

However, the corrosive impact of far-right ideology becomes more palpable as the action shifts to Europe, where and we encounter the Vladboys, an anti-semitic biker gang, and a host of “Hitler-happy adolescents” doomed “to be brought down as prey… at the hands of those they thought were brothers in a struggle.”

Few writers become adjectives: the terms Kafkaesque, Orwellian and Dickensian evoke a specific style and set of concerns. Pynchon may be the only living example of this. Shadow Ticket is a less daunting book than Gravity’s Rainbow, V and Against the Day, but retains the defining characteristics of Pynchonesque. It tackles the author’s well-established obsessions — conspiracy, deception, the abuse of power, social regimentation, the dark side of capitalism, the psychological impact of technology and, perhaps most notably, the nature of storytelling.

This last element is evident in the book’s supernatural symbolism, including a miniature Czech golem and the teleportation of objects — and its relentless genre blending. The tale lurches between pulp mystery, conspiracy thriller, steampunk fantasy, surreal comedy, political satire and literary pasquinade.

Shadow Ticket demands a high level of concentration. The extensive dialogue, vital to a full understanding of the book’s allegiances, deceptions and schemes, is labyrinthine and sometimes untagged.

The effort will, however, be repaid in full. This is a hugely enjoyable but deadly serious examination of the 1930s, a decade of competing worldviews, charismatic villains, violent repression, ethnic prejudice, corrosive change and blatant assaults on the truth.

And, as humanity hurtles into another dangerous bend in the road, it’s a searing indictment of our own era.