SUSAN DARLINGTON swoons in the presence of a magnetic frontman

For his study of anti-Muslim Muzaffarnagar Riot, HENRY BELL applauds Joe Sacco for a devastatingly effective combination of graphic novel and investigative journalism

[Pic: courtesy of Jonathan Cape]

[Pic: courtesy of Jonathan Cape]

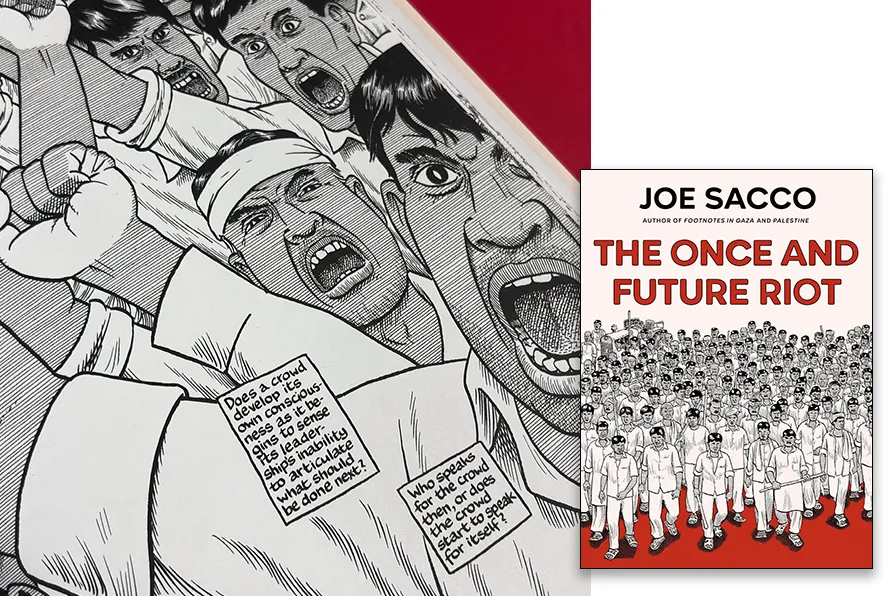

The Once and Future Riot

Joe Sacco, Jonathan Cape, £20

WHEN the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) came to power in India in 2014, riding a wave of far-right and anti-Muslim rhetoric, backed by a corporate media, it seemed like a shocking step backwards. The coronation of the stokers and instigators of communal violence and misinformation in a longstanding democracy was surely an aberration.

As it transpired, however, the Indian result was a bellwether for the world. In the more than a decade that has followed, the election of far-right populists and the use of street violence as a part of their political toolkit has been proven to be the norm, not the exception for the 21st century.

The BJP remains in power in India.

In his new book The Once and Future Riot, Joe Sacco, the Maltese-American comics-journalist, takes us into the heart of communal violence and anti-Muslim pogroms in India. He does not begin with their inception amidst the devastating violence and displacement of the 1947 British Partition of India; or the starting point of the BJP ascension, the mob demolition of the Babri Masjid in 1992; nor does he focus on the defining violence of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s career, the Gujarat riot of 2002 which left more than 1,000 Muslims dead.

Instead Sacco takes us to 2013 and the relatively little known riot in Muzaffarnagar that killed between 60 and 100 people. Set in northern India on the brink of the Hindutva movement taking power, the book paints a complex and nuanced portrait of the overlapping economic, caste and political concerns that led to the violence, and how that violence was utilised by politicians.

The combination of graphic novel and investigative journalism has been proven by Sacco to be devastatingly effective when invoking and explaining atrocities – his books on Palestine and Bosnia amply demonstrate this.

Similarly in The Once and Future Riot, the combination of personal testimony with the deeply absorbing and meticulously detailed depiction of life in Uttar Pradesh powerfully locate the reader inside the story and repeatedly humanise and de-exoticise both the victims and perpetrators of communal violence. The medium here allows for shocking and contradictory things to be said by the protagonists without their humanity or their material situation ever receding from view.

One of the astonishing strengths of comics journalism as a form, and Sacco’s own style as an artist, is the ability to depict – with equal weight – differing accounts of the same incident. And so we see memories that cannot be corroborated, or established, but that nevertheless become crucial to feeding the escalating tensions. Tensions that always have class dimensions at their centre.

The detailed drawings of each contradictory account of how the violence started are layered in such a way that narrative and media become the key protagonists in the spread of communal violence. Rumours, lies, Whatsapp messages and fake videos on social media are the driving force in the story.

Whilst we might, with broad brushstrokes, depict communal violence in India as essentially anti-Muslim, Sacco demonstrates how India’s minorities are used more widely by the ruling class, and how caste as well as religion is used to divide and rule – without ever losing site of the essentially Hindu-nationalist nature of the violence.

In Muzaffarnagar it is the Socialist Party’s courting of the Muslim vote that lights the touch-paper for the mob violence of Hindu Jats – a land-owning peasant caste. Sacco depicts the corrupt ruling elites of the SP and BJP as well as the contradictory communal sympathies of different layers of the police force and judiciary with great clarity, and due credit to his local colleague Piyush Srivastava.

Joe Sacco has built his reputation on the scrupulous investigation of societal conflict. His work in India is a departure in that it takes him away from war, but its themes are the same. How do humans come to destroy each other, what are layers of dehumanisation, corruption and violence that allow massacres to happen and how should we respond to them?

The Once and Future Riot concludes with a look at the corrupt compensation systems and discrediting of victims led by local politicians – a notable exception being the resettlement village built in Shamli district for displaced victims of the riot by the CPI (Marxist).

Though it is deeply rooted in Muzaffarnagar District, it is India and the world’s political use of communal violence that is the central subject of the book. As Sacco puts it “bloodshed is a political building block.” And in India, as in the USA and the UK, politics that relies on communal violence and bigotry, is inevitably consumed by it.