New releases from Bill Callahan, The Delines, and Beck

RICHARD CLARKE welcomes a study that extends an understanding of Marxism beyond human society to encompass the whole of nature

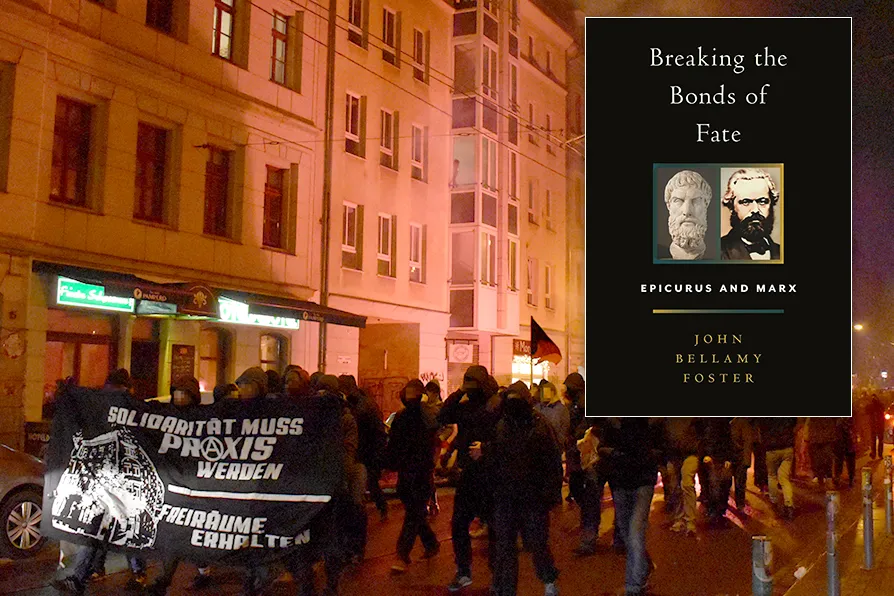

PROTEST AS PLEASURE: Anarchist banner in Dresden, Germany, translating to "Solidarity must become praxis", January 2020 [Pic: Protestfotografie Dresden/CC]

PROTEST AS PLEASURE: Anarchist banner in Dresden, Germany, translating to "Solidarity must become praxis", January 2020 [Pic: Protestfotografie Dresden/CC]

Breaking the Bonds of Fate: Epicurus and Marx

John Bellamy Foster, Monthly Review Press, £18.75

EPICUREAN is commonly understood as a reference to gourmet food and drink, or more generally to a hedonistic lifestyle. Google a little deeper and you’ll find that Epicurus was a Greek philosopher who tells us that pleasure is the highest good; not wild indulgence but a tranquil state (ataraxia) achieved by removing pain (aponia) through simple living, friendship, limiting desires to natural and necessary ones (food, shelter, safety), and working collectively to secure true, lasting happiness.

And if you’ve read up on the origin of Karl Marx’s world view you’ll have come across the argument that his doctoral thesis, The Difference Between the Democritean and Epicurean Philosophy of Nature (completed in 1841 and dedicated to Ludwig von Westphalen, his friend, mentor and future father-in-law), was merely an aberration or youthful enthusiasm soon overtaken by his developing political awareness and activity.

In reality, argues John Bellamy Foster, the opposite is the case. Marx’s study of Epicurus and his relation to it was central to the development of Marx’s world view.

Foster is one of the most prominent of today’s Marxist academics who have “rescued” the ecological Marx (and Engels), and promoted the notion of a “second foundation” of Marxism; extending our understanding of Marxism beyond human society (historical materialism and the critique of political economy) to encompass the whole of nature.

For Foster, Epicurus and Marx are individuals of equivalent stature: even Marx couldn’t “make bricks without straw”. One example: Marx’s well known statement about standing Hegel on his feet seems to have come from Epicurus’ Roman populariser, Lucretius, who said of the idealist philosophers of his day that they stood with their heads where their feet belong.

Recent studies of Epicurus’ major work, On Nature — based on fragments of carbonised papyri stored in a library in the Roman town Herculaneum, buried in volcanic ash when Mt. Vesuvius erupted in 79 CE and discovered in the mid-18th century — demonstrate that Marx’s 19th-century treatment of Epicurus is broadly correct. Breaking the Bonds of Fate builds on this understanding and transforms the way we see both figures and their relevance today.

In four chapters, Foster leads us successively through a structured exposition and analysis of Epicurus (341-270 BCE) and his location within Athenian society; of his materialist (and dialectical) philosophy; of the contents of Marx’s own doctoral thesis; and of the links between Epicureanism and Marxism today.

The whole is invaluable for a number of reasons. It provides insight into the origins of Marx’s thought and work. As the author declares: “If Marx was the first to penetrate to the essence of Epicurus’ philosophy, the study of Epicurus enables us to uncover the essence of Marx.”

Epicurus provided Marx with the basis for a materialist, anti-idealist worldview that understood both nature and human history as evolving, material processes. And (for this reviewer at least) it provides a new understanding of the relationship between freedom and necessity, of praxis, ancient and modern.

Breaking the Bonds of Fate is both scholarly and at the same time an accessible treatise on the origins and development of Marx’s thought, on its relationship to Greek philosophy and, most importantly, on the philosophical foundation for action.

Foster explicitly rejects any linear or teleological reading of Marxism. History is not linear; it has no built-in direction. Class struggle does not inevitably lead to socialism. What it does is provide the possibility and means for achieving it.

“Changing the world” is up to us!