MARIA DUARTE and ANDY HEDGECOCK review The Tasters, A Pale View of Hills, How To Make a Killing, and Reminders of Him

GAVIN O’TOOLE welcomes a book that sets the assassination of Brian Thomson in the context of radical individualism — lost in a vast pick-and-mix of ideologies

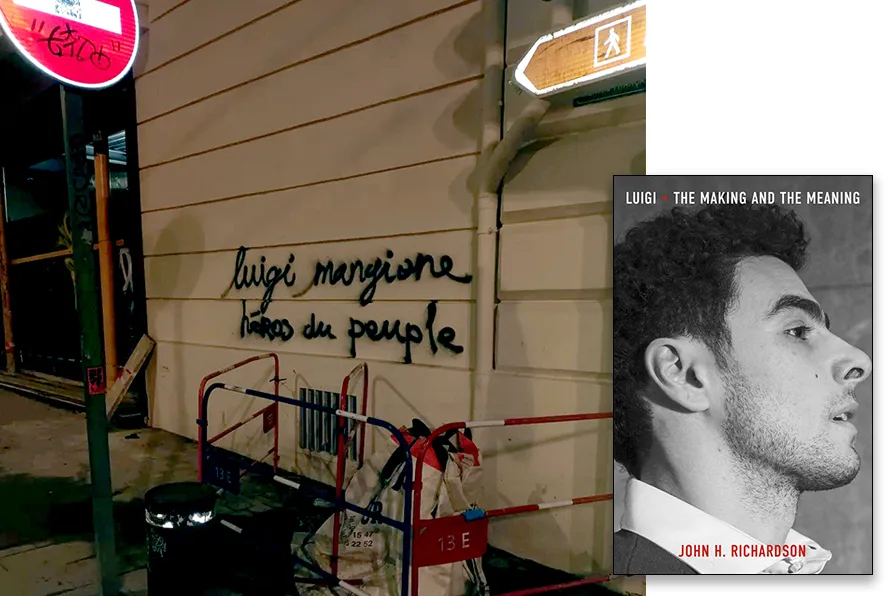

NEBULOUS REPUTATION: "Luigi Mangione, hero of the people" graffiti in French in Marseilles, France. [Pic: insignificunt1312/CC]

NEBULOUS REPUTATION: "Luigi Mangione, hero of the people" graffiti in French in Marseilles, France. [Pic: insignificunt1312/CC]

Luigi: The Making and the Meaning

John H Richardson, Simon & Schuster, £20

MAINSREAM debates in nominally liberal democratic societies twist into unrecognisable contortions at any attempt to justify political violence by actors outside the state.

This reflects a blind hypocrisy that ignores the violence on which capitalism is, literally, constructed, while hyperventilating about the explosive frustrations it occasionally provokes among its victims.

The deadly unilateral act allegedly committed by Luigi Mangione — the shooting of UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson in December 2024 — was undoubtedly an explosive frustration, but to what extent was it a political challenge to a fragile status quo?

This question forms the substrate of John Richardson’s unusual biography of a Gen Z anti-hero beatified by many radicals as a modern Robin Hood and condemned by the US federal establishment as a real and present danger whom they must execute to save the world.

The task Richardson sets himself is to identify the ideological motives of the latest poster-boy of radicalism, and he does so through a forensic analysis of his social media history, reading lists, written work, and the comments of interlocutors and friends.

In one sense, it’s a small masterpiece of research into contemporary political ideas, even if evidence of Mangione’s affiliations are scant given his youth and contradictions; but in another it is predictable to the extent that, by the end of the book, no clear conclusion can be drawn.

From the information available, Mangione is no terrorist — something that in September a judge also concluded, dismissing terrorism charges against him — nor revolutionary, nor even socialist.

Neither is he an anarchist or nihilist and if, as Richardson implies throughout the book, he loosely adhered to the lone-wolf spirit of Unabomber Ted Kaczynski, he was ambivalent about the latter’s apocalyptic instincts.

Kaczynski, who has become an icon in some US anarchist and libertarian circles, is an important protagonist of this book with whom the author had conducted a lengthy correspondence prior to the Mangione case.

Accordingly, Richardson returns to praise for Kaczynski’s prescience uncomfortably often, although, to underline Mangione’s own eclecticism, he begins by pointing out his initial rejection of calls to violence.

The picture that then emerges is of a confused, angry yet compassionate young man with back pain floundering in an ocean of ideological possibilities in which entire generations grappling with existential angst now find themselves adrift.

Which brings us to the real value of this book.

First, this was an individual act of violence that has had significant political implications because, putting the chest-beating aside, Thompson embodied the amoral profiteering of his class, his own crimes magnified precisely because they contradicted the very ethos of healthcare.

When slotted into the longue duree of history, Mangione’s alleged crime might then be considered to have been a valid act of resistance against the bloody juggernaut of capitalism.

Notwithstanding this, however, Richardson notes that Mangione also flirted with ideas on the far right, and there is simply insufficient evidence to say how far down the anticapitalist road he may have travelled.

Second, as an individual act absent a clear strategic motivation founded in a coherent analysis, this shooting is of negligible utility to the unglamorous collective slog confronting socialists in building a revolutionary movement.

That is not to say the onward march of socialism is never violent — its history is soaked in blood and, although Marx only paid perfunctory attention to this, it is self-evident that revolution never comes cheap.

And finally, and most importantly, leading on from this, Mangione reflects the consequences of the revolutionary left’s failure to build a movement that can channel the “beautiful promise” represented by wannabe Robin Hoods throughout history.

As Richardson suggests, Mangione is nothing if not a reflection of where politics has taken a society which lauds radical individualism — a vast pick-and-mix confectionary of ideologies, conspiracies and hybrid movements turbocharged by social media and AI.

The author reaches this conclusion late, writing: “But in the end, pinning down Luigi’s motive misses the point. Luigi’s elusiveness is what really matters.”

He has become a screen on which helpless, desperate Americans peppered randomly along the left-right spectrum can project their dreams and fears — a ghost in the matrix.