To Besiege A City: Leningrad 1941-42

Prit Buttar , Osprey, £30

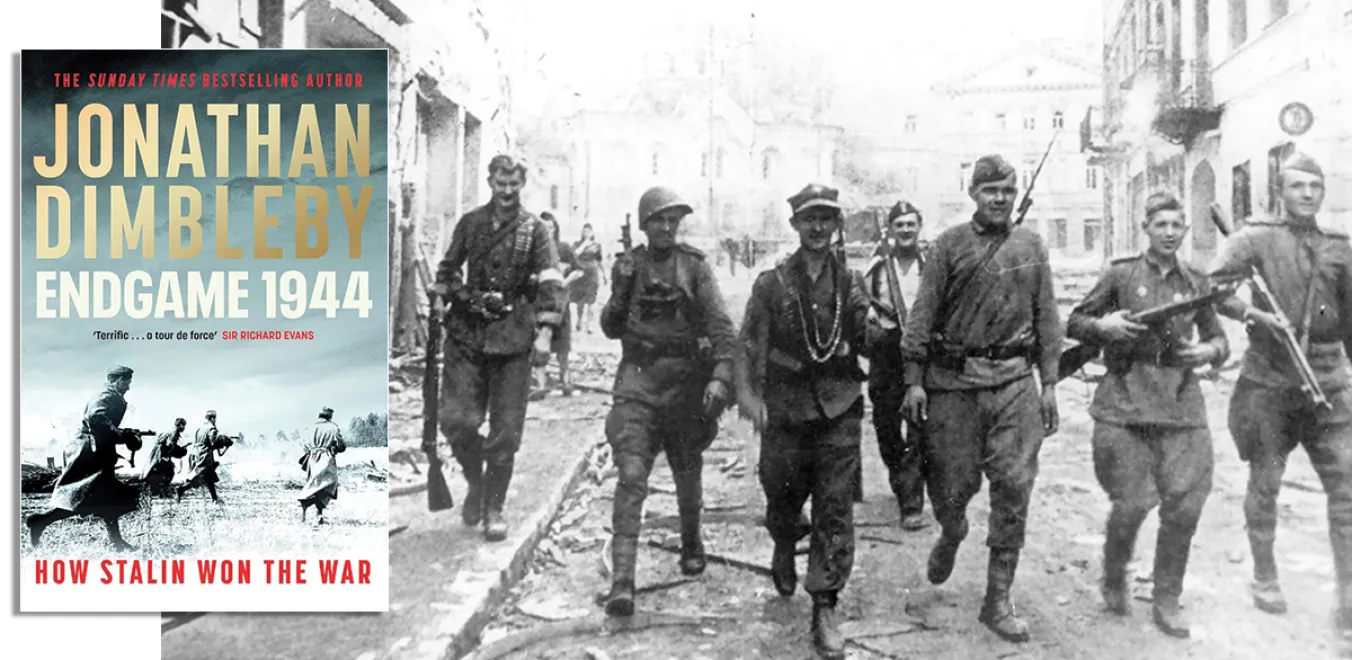

RETIRED GP, ex-British army surgeon and prolific historian Prit Buttar has published his latest book in the Eastern Front series. To Besiege a City: Leningrad 1941-42 relives the infamous Axis-enforced blockade, during which hundreds of thousands of the city’s residents died from starvation and associated causes, and details the bloody battles that took place within the Leningrad sector between 1941-42.

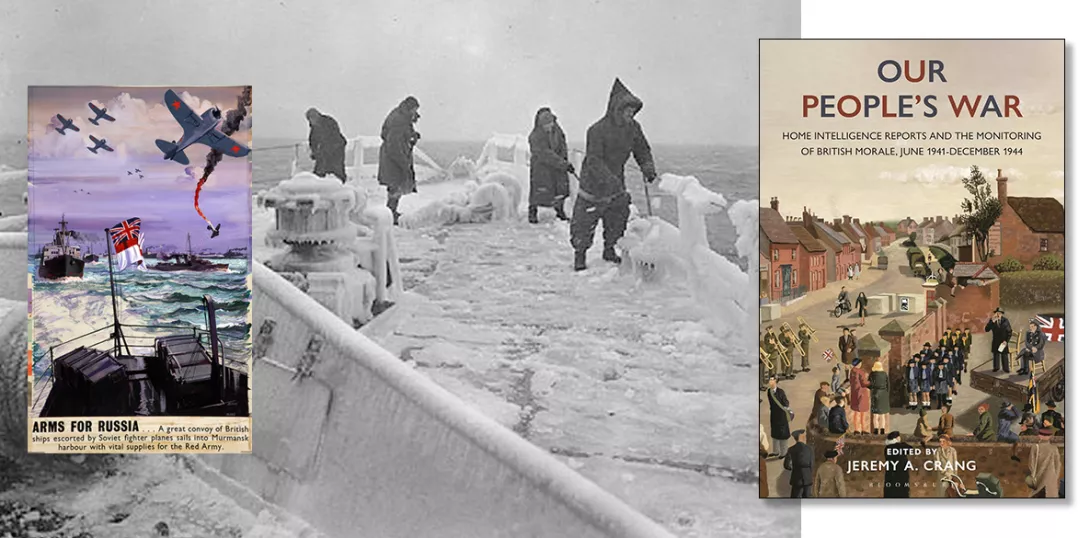

During this time, the Wehrmacht alternately planned to either occupy Leningrad or starve the city’s population into submission. Concurrently, the Soviet Red Army fought tooth and nail to lift the siege or at least accomplish the uphill task of keeping the city’s defenders and civilians supplied with sufficient food, ammunition and other essential supplies.

Buttar’s 400-plus page endeavour begins with the extraordinary story of how the ambitious and eccentric Russian tsar Peter the Great was determined to found a prosperous new city in a remote and inhospitable part of Russia during the early 18th century. He notes the colossal effort, (not least in terms of wealth and the lives of peasants and prisoners) that such an ambitious undertaking mandated.

Tsar Peter I had been inspired by modern ideas and inventions encountered during his travels around Europe. He sought to build a city to reflect these ideas and serve as a cultural and mercantile window to the west. Named after its founder, St Petersburg was born and subsequently thrived against the odds.

The story of the city’s birth and its subsequent history is said to have forged a unique and indefatigable spirit: it would temporarily become the capital of tsarist Russia, serve as the cradle of the Russian Revolution, successfully repel invading White Russian forces during the civil war, and become the only Soviet city successfully to resist prolonged siege warfare during World War II.

Buttar not only provides a meticulous account of life within the besieged city but also details the bloody offensives and counteroffensives that took place during 1941-42, battles which caused high casualty rates among both Axis and Soviet forces whilst the front line barely changed.

He duly pays respect to the bravery and determination of Leningrad’s inhabitants and defenders, whose ingenuity and resolve helped them survive the catastrophic winter of 1941 when all seemed lost.

Buttar also explains why Soviet losses during the battles of 1941-42 were much higher than they ought to have been, citing several factors including the consequences of Stalin’s pre-war purge of the Red Army’s leadership, the army’s reliance on outdated dogmas and tactics, and a lack of communication and co-ordination between its various branches. Furthermore, a widespread fear among the officer class dissuaded commanders from acting independently or reacting to changing events on the battlefield as even a slight deviation from original orders could result in their arrest and denunciation.

Buttar’s scholarship incorporates diary extracts and other original sources to illustrate the experiences of how Leningrad’s civilians struggled to survive against all odds. These primary sources also give insights into the thoughts and feelings of generals, officers and enlisted men of both the Red Army and Wehrmacht who partook in the conflict.

While the book at times goes into excessive amounts of detail about the events of the Leningrad front between 1941-42, it brings to life a dark chapter of World War II history that ought to never be forgotten.

Buttar does justice to the heroic city and its defenders, who remained unbroken in the face of the unrelenting might of the Nazi war machine while also having to contend with the consequences of an inflexible and solid Soviet bureaucracy.