When Patterson and Liston met in the ring in 1962, it was more than a title bout — it was a collision of two black archetypes shaped by white America’s fears and fantasies, writes JOHN WIGHT

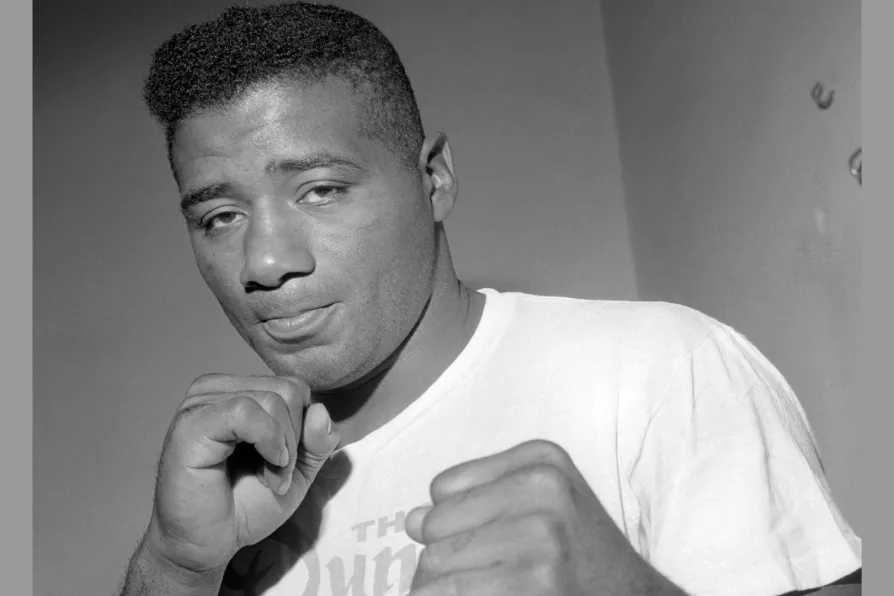

Former World Heavyweight champion Floyd Patterson in London, 1966

Former World Heavyweight champion Floyd Patterson in London, 1966

TWO of the most disdained and maligned fighters in the history of boxing — Floyd Patterson and Sonny Liston — were also two of the most misunderstood.

Patterson was a poster boy for black integration while Liston stood as a totem of black alienation. Where Patterson was sensitive and shy, Liston was angry and malevolent. Thus the stage was set for the good guy versus bad guy clash so beloved by devotees of all things American and Americana.

They met in the ring twice. Their first clash took place on 25 September 1962 at Chicago’s Comiskey Park, home to the city’s famed Chicago White Sox baseball team. A crowd of 19,000 turned up to watch the bout live. Closed circuit television was in its infancy at the time, with this fight one of the first to be aired live around the country using the new technology. Such was the interest in the fight, it was shown at 264 venues across the United States and Canada.

The incumbent champion, Patterson, carried into the ring the shallow expectations of white liberal America — specifically that good should always triumph over evil. It was this rendering of the fight that elevated it from the realm of sporting contest to the realm of allegory, with Liston cast as the surly and rebellious “field negro” to Patterson’s domesticated “house negro,” whose chief role was to keep the former in line.

Covering the fight were some of America’s most legendary novelists and writers not only of their time, but of all time. Norman Mailer, Nelson Algren, James Baldwin, Ben Hecht and Budd Schulberg had each been assigned by various publications to mine the bout’s deeper meaning for the mass reading audience that then obtained to the extent that it does not today.

Of the aforementioned, Baldwin arrived on the scene with no knowledge of boxing whatsoever. “I know nothing whatever about the Sweet Science or the Cruel Profession of the Poor Boy’s Game. But I know a lot about pride, the poor boy’s pride, since that’s my story and will, in some way, probably, be my end.”

Press agent Harold Conrad was rather more blunt when appraising Baldwin’s boxing bona fides, quipping that he did not “know a left hook from a kick in the ass.” But what Baldwin brought to the event instead was the profound sensibility of a gay black man at time in America when to be either was to be scorned, and to be both was to find yourself consigned to the status of a social leper.

Baldwin: “Patterson was, in effect, the moral favourite — people wanted him to win, either because they liked him, though many people didn’t, or because they felt that his victory would be salutary for boxing and that Liston’s victory would be a disaster.”

Sonny Liston was the Mike Tyson of his day — a man who did not just want to defeat his opponents, he wanted to damage them. The 24th of 25 children, Liston’s exact year of birth remains unknown to this day. What is known is that his father was a poor cotton-picker and violent tyrant who regularly attacked his kids with a belt buckle. Under such conditions the result is either growing up to abhor violence or to embrace it.

Sonny went the latter route and wound up in prison for armed robbery. It was while inside that he took up boxing, relishing the opportunity it provided for being able to beat other men into a pulp without getting into trouble for it.

James Baldwin was one of the very few writers who saw the vulnerability and pain concealed behind Liston’s menacing exterior. Upon visiting Liston’s training camp prior to his first clash with Patterson in 1962, Baldwin wrote: “It seems to me that he [Liston] has suffered a great deal. It is in his face, in the silence of that face, and in the curiously distant light in the eyes — a light which rarely signals because there have been so few answering signals.”

Floyd Patterson’s peek-a-boo-style was the brainchild of legendary trainer Cus D’Amato. It was designed to turn the disadvantage of his lesser height compared to other heavyweights into an advantage — this by coming in low, bobbing and weaving, to get inside his opponent’s jabs and right crosses before coming up with thunderous hooks and uppercuts. It was a style that Mike Tyson, another D’Amato protege, would use to devastating effect three decades later.

Patterson’s biggest weakness was one that currently afflicts former heavyweight champion Anthony Joshua in our time. That weakness is over analysis. Analysis leads to paralysis, they say, and this is never more revealed to be true than in a boxing ring.

Indeed in Patterson’s case, his mind, not Sonny Liston, was his deadliest opponent. Prior to their first fight in Chicago Patterson arranged for two cars to be made available outside the stadium. One was to take him straight back to his hotel in the event of victory, while the other had been arranged to take him straight home to New York in the event of defeat. He also had in his gym bag on the night a fake beard and glasses so that he could leave the stadium without being recognised if he lost.

Not only did he lose in Chicago against Liston, Patterson was subjected to a merciless hiding. Baldwin: “It was scarcely a fight at all … Floyd seemed all right to me at first. But Liston got him with a few bad body blows, and a few bad blows to the head. Floyd went down. I could not believe it.”

The end result provided white America with its worst scenario possible — a heavyweight champ who looked and carried himself like, per the great Curtis Mayfield, the “nigga in the alley” of their worst nightmares. It was a victory for black alienation over black integration.

Little did they know that coming down the track was the even more potent symbol of blackness in the shape of one Cassius Clay, a fighter destined to represent neither black alienation nor integration, but liberation.

JOHN WIGHT tells the riveting story of one of the most controversial fights in the history of boxing and how, ultimately, Ali and Liston were controlled by others

The outcome of the Shakespearean modern-day classic, where legacy was reborn, continues to resonate in the mind of Morning Star boxing writer JOHN WIGHT