For his study of anti-Muslim Muzaffarnagar Riot, HENRY BELL applauds Joe Sacco for a devastatingly effective combination of graphic novel and investigative journalism

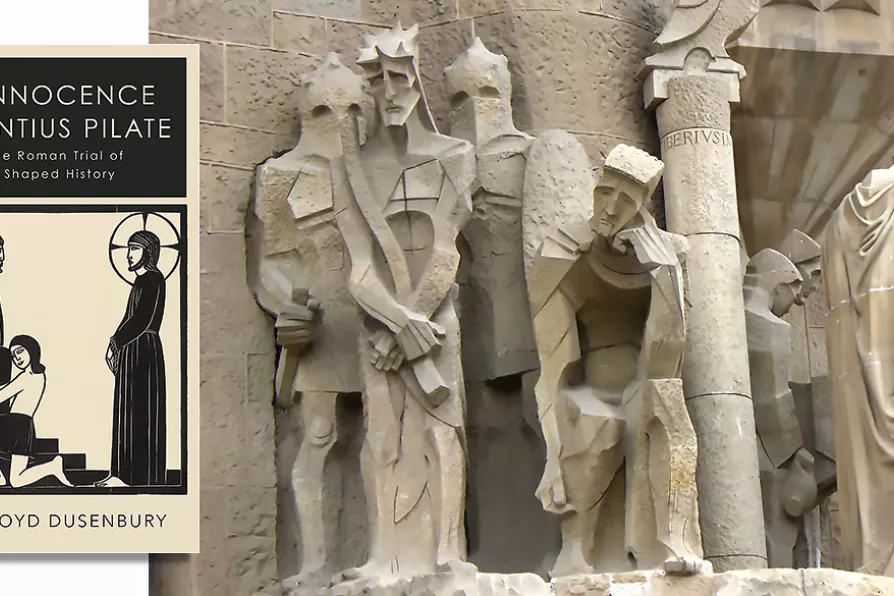

TRUE DILEMMA: Antoni Gaudi’s La Sagrada Familia, Barcelona, Passion facade (detail) with Jesus and Pontius Pilate by catalan sculptor Josep Maria Subirachs

[Rp22/CC]

TRUE DILEMMA: Antoni Gaudi’s La Sagrada Familia, Barcelona, Passion facade (detail) with Jesus and Pontius Pilate by catalan sculptor Josep Maria Subirachs

[Rp22/CC]

The Innocence of Pontius Pilate: How the Roman Trial of Jesus Shaped History

David Lloyd Dusenbury

Hurst, £25

DAVID LLOYD DUSENBURY, philosopher and senior fellow at Budapest’s Danube Institute, undertakes an in-depth analysis of a pivotal event in the history of Christianity that could be arguably deemed the most famous trial in human history.

In the Innocence of Pontius Pilate, Dusenbury methodically examines the judicial proceedings in which Roman governor Pontius Pilate questioned Jesus Christ in a trial that culminated in the latter’s crucifixion and (according to Christian belief) resurrection. Dusenbury looks at how the trial is described in the four canonical Gospels of the New Testament as well as how religious scholars and philosophers reported and interpreted the event during subsequent centuries.

Dusenbury’s scholarly work begins by seeking to determine whether or not Pilate, who governed the Roman province of Judaea in the early 1st century AD, can be considered guilty of Jesus’s death. Dusenbury reveals that this question, which some might consider straightforward, is, in fact, a matter of great complexity from both legal and religious standpoints.

SYMON HILL looks at Tommy Robinson’s bid to use Christmas to spread division and hate — and reminds us that’s the opposite of Jesus’s message

GORDON PARSONS is enthralled by an erudite and entertaining account of where the language we speak came from

LOUISE BOURDUA introduces the emotional and narrative religious art of 14th-century Siena that broke with Byzantine formalism and laid the foundations for the Renaissance