Where Children Sleep, vol 2

James Mollison, Hoxton Mini Press, £35

[[{"fid":"59759","view_mode":"inlineleft","fields":{"format":"inlineleft","field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]":false,"field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]":false},"link_text":null,"type":"media","field_deltas":{"1":{"format":"inlineleft","field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]":false,"field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]":false}},"attributes":{"class":"media-element file-inlineleft","data-delta":"1"}}]]

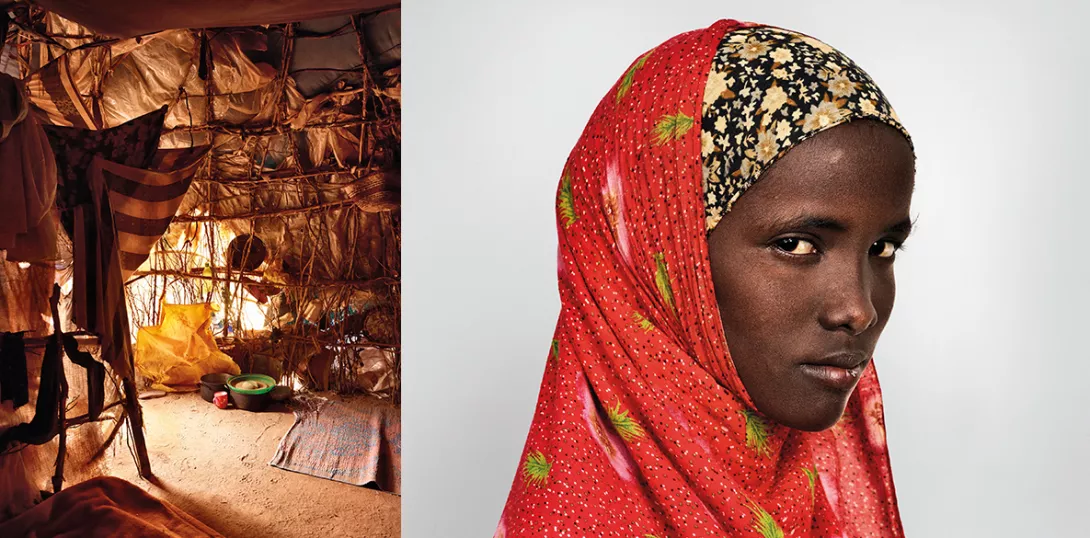

THIS is the second volume in James Mollison’s ongoing photographic project that documents the varied conditions in which children live, sleep and dream across the globe. Here, he touches upon the fast-changing issues of climate change and gender.

His photographs carefully show the innocence and injustice within their lives. Mollison doesn’t tell readers what to think but gently guides us by what he chooses to depict, exploring the modern world through a childlike lens. His non-judgemental eye is evident in how each page varies in composition, location, story and tact.

The book is not ordered by wealth, class or geography. In fact, Where Children Sleep’s heterogenous layout demonstrates how we are all interlinked, revealing as both a beautiful and terrifying truth. As such, the book evokes a real sense of responsibility for our younger generations.

Mollison’s photos are maximalist in their composition. Detailed with toys, clothes, materials and people, his portraits are packed with feeling. Additionally, in the cases where children are suffering, Mollison’s maximalism combats a Western desensitisation to tragedy overseas. With these photos, the children are no longer strangers to the readers.

Indeed, this approach is especially important when a Palestinian genocide is happening on our screens. Mollison’s photography demonstrates that each child is not a statistic but a real individual with family, pets, hobbies, fears and hopes for the future. The book promotes humanity.

For many, childhood is a privilege. Concerns about consumerism, climate change, poverty and civil wars are strikingly personal to these children. Five-year-old Rawan lives in a Zaatari refugee camp and his night life is shaped by regular nightmares about death.

Mollison also identifies poverty in some of the richest countries of the world. Alex, a US kid, lives in a crowded trailer park, his family is struck by the opioid crisis. His family’s clothes and possessions clutter the frame, messily strewn almost like shrapnel.

In the organised or messy placement of kid’s possessions, Mollison captures innocence that is in the unjust process of being stripped away or perfectly preserved on the backs of others. Another US boy lives in idyllic consumerist comfort. Superman merchandise is positioned an equal distance apart all around his room. He proudly poses in his Superman costume — a quintessentially US image.

Mollison’s straightforward text reinforces his work’s poignancy. Of 11-year-old May, a member of the Inupiaq in northernmost Alaska, Mollison writes that “she likes school, but not the bullying.” Apparently, when the family is doing well financially, they buy orange juice and noodles. May educates us about rising food prices for indigenous communities and we find ourselves learning from these children.

In another point of education, Mollison engages in popular topics. He helps alleviate some fear around transgender youths by showing the normalcy of their lives. Fourteen-year-old Phonlaphat wants to go to university so they can express their gender identity more accurately. They describe themself as “kathoey — transgender person, male assigned at birth.” Mollison writes about how transgender people have been in Thai texts and heritage for 700 years.

Another trans kid covers half her face and is considering puberty blockers so that she can reverse her transition if necessary. Mollison gives rare and trusted insight.

In short, Mollison’s photographs show how kids exercise identity through toys which they collect, organise, ruin or treasure. The bedroom is a place where children explore their social roles within their respective communities.

With this motif, Mollison creates a quiet protest — as the blurb states: “All children need to sleep, but not every child has a bed.”

Mollison commands attention to children’s stories that are underlooked — lives that are full of opportunity yet governed by the past. In short, the children’s bedroom emerges as a space of preparation, hence its preciousness.

Mollison’s book pushes for the preservation of childhood, at a time where world leaders and citizens alike desperately need to listen.