JOHN GREEN, MARIA DUARTE and ANGUS REID review Fukushima: A Nuclear Nightmare, Man on the Run, If I Had Legs I’d Kick You, and Cold Storage

The emancipatory eye

JOHN GREEN marvels at the rediscovery of a radical US photographer who took the black civil rights movement to her heart

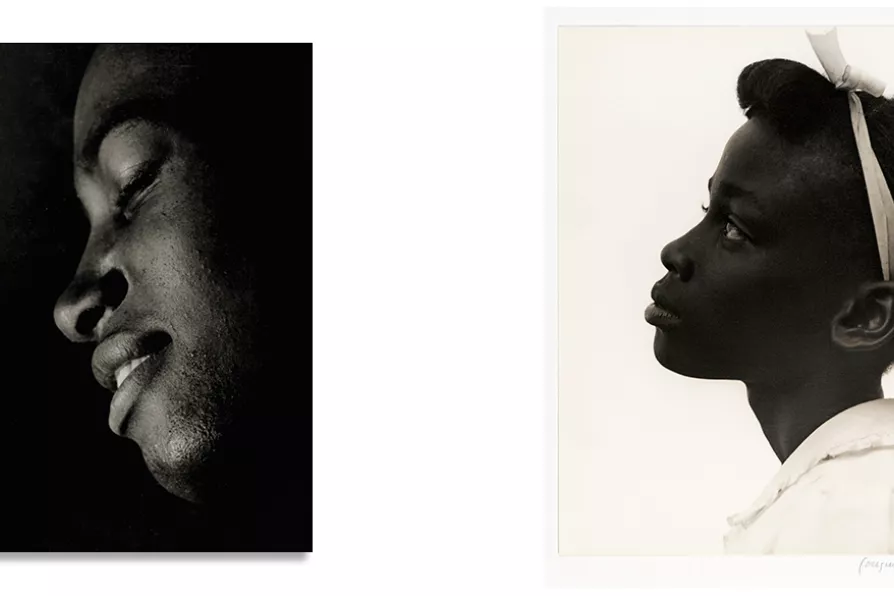

Consuelo Kanaga. Young Girl in Profile, 1948.

[© Brooklyn Museum]

Consuelo Kanaga. Young Girl in Profile, 1948.

[© Brooklyn Museum]

Consuelo Kanaga – Catch the Spirit

Drew Sawyer, Thames & Hudson, £50

Consuelo Kanaga. Fire, New York, 1922. Credit: © Brooklyn Museum

FEW will have come across the name Consuelo Kanaga (1894–1978), although she was one of the most influential US photographers during the first half of the 20th century. She suffered the same fate as so many women artists: consigned to the museum of amnesia. It is therefore cause for celebration that T&H, together with the Brooklyn Museum and Mapfre have collaborated on this volume dedicated to her work and helping rescue her from oblivion.

Similar stories

Peter Mitchell's photography reveals a poetic relationship with Leeds

Ben Cowles speaks with IAN ‘TREE’ ROBINSON and ANDY DAVIES, two of the string pullers behind the Manchester Punk Festival, ahead of its 10th year show later this month

JOHN GREEN surveys the remarkable career of screenwriter Malcolm Hulke and the essential part played by his membership of the Communist Party

ANDY HEDGECOCK relishes two exhibitions that blur the boundaries between art and community engagement