GORDON PARSONS is bowled over by a skilfully stripped down and powerfully relevant production of Hamlet

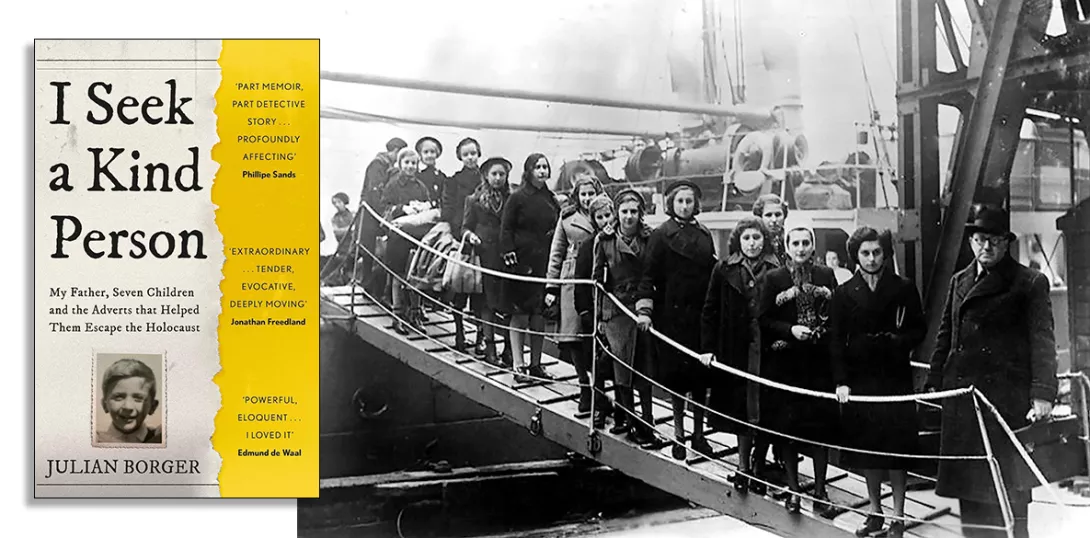

The kindness of strangers

SUE TURNER recommends an eloquent exploration of the subsequent lives of Jewish child refugees to Britain

I Seek a Kind Person - My Father, Seven Children and the Adverts that Helped Them Escape the Holocaust

Julian Borger, John Murray, £20

JULIAN BORGER was 22 when his father Robert committed suicide. Many years later Borger decided to investigate his father’s background in order to achieve some understanding of what led him to take his own life.

The result of his research has been this book; a powerful synthesis of memoir, detective work into family mysteries and a narrative of the wider political events that impinged on the Borger family through the 20th century and which influenced their decision making.

More from this author

The phrase “cruel to be kind” comes from Hamlet, but Shakespeare’s Prince didn’t go in for kidnap, explosive punches, and cigarette deprivation. Tam is different.

ANGUS REID deconstructs a popular contemporary novel aimed at a ‘queer’ young adult readership

A landmark work of gay ethnography, an avant-garde fusion of folk and modernity, and a chance comment in a great interview

ANGUS REID applauds the inventive stagecraft with which the Lyceum serve up Stevenson’s classic, but misses the deeper themes

Similar stories

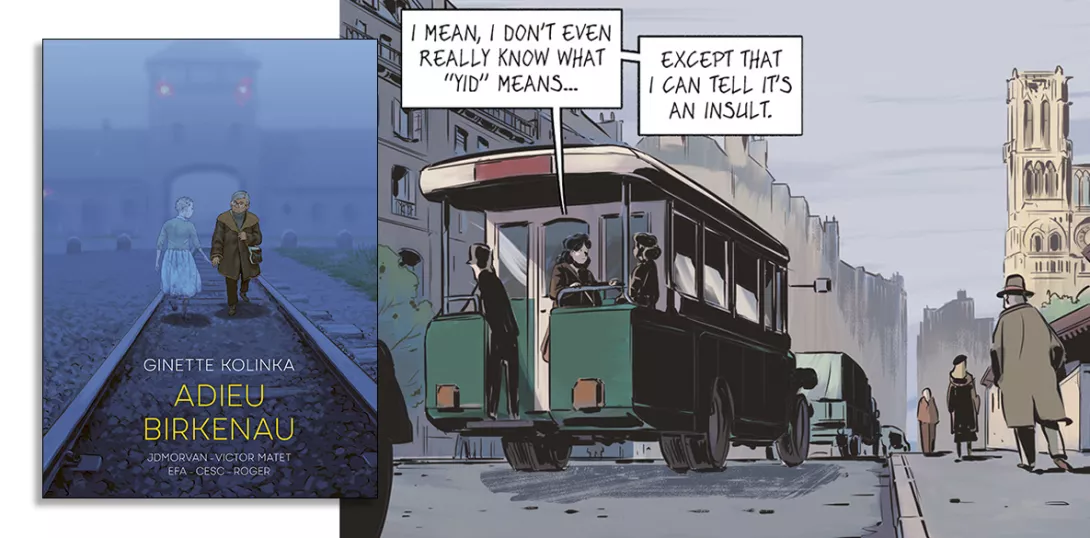

FIONA O’CONNOR detects contemporary relevance in the depiction of a society heading into the abyss while the world does nothing

Robert Kennedy Jnr, in endorsing Donald Trump for president, claims things will be different under his influence and that Trump will ‘honour his word.’ That would be a historic but totally unlikely first, writes LINDA PENTZ GUNTER

MARIA DUARTE is chilled by a documentary that brings together the son of Rudolf Hoss with a Jewish Auschwitz survivor

DAVID HORSLEY honours the black British communist who fought the fascists from Cable Street, to Spain, to the concentration camps of Nazi Germany