BRENT CUTLER recommends a sober examination of the real risks and true merits of nuclear energy, and an exposure of the capitalist system as an obstacle to human betterment

Genocide, then and now

FIONA O’CONNOR detects contemporary relevance in the depiction of a society heading into the abyss while the world does nothing

[Ricard Efa and Cesc F Dalmases]

[Ricard Efa and Cesc F Dalmases]

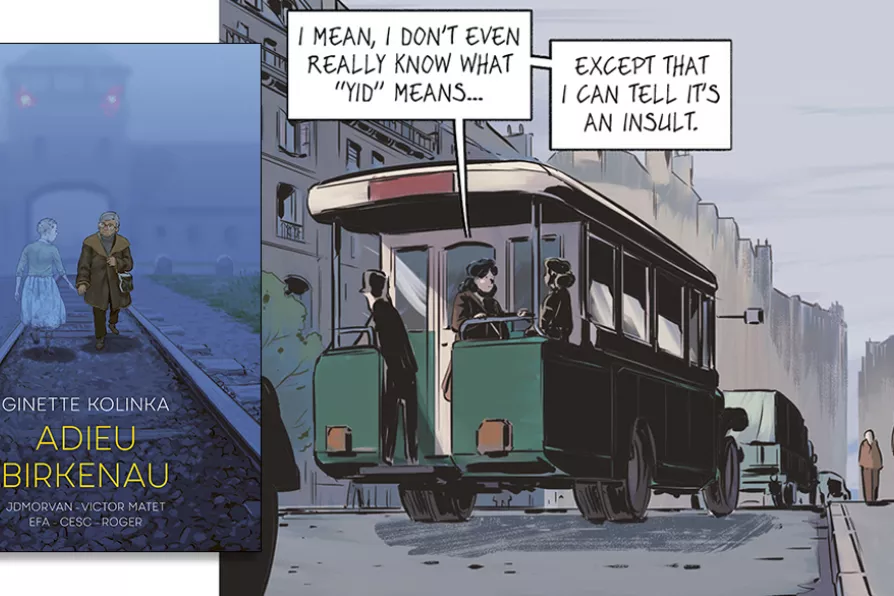

Adieu Birkenau

By Ginette Kolinka, JD Morvan and Victor Matet, SelfMadeHero, £19.99

IN our present predicament this graphic novel, written by a survivor of Nazi extermination camps, is a valiant testament to the power of witness.

Ginette Kolinka is a Parisian Jew halfway through her ninth decade. In 1941 she and her family escaped Nazi Paris only to be arrested by German authorities in the free zone.

She was imprisoned and then transferred to the SS-controlled internment camp at Drancy. As part of “the Final Solution” she was transported with her father and her younger brother, Gilbert, to Auschwitz II-Birkenau.

Similar stories

JAMES WALSH is moved by an exhibition of graphic art that relates horrors that would be much less immediate in other media

ANDY HEDGECOCK welcomes an explanation of genocide by the persecuted author that is both uplifting and important

JOHN GREEN takes issue with a mainstream novel designed to denigrate the GDR

STEVE SILVER tells the horrifying story of the Nazis' last act of mass barbarity when they forced tens of thousands of prisoners in the camp to march into the snow at gunpoint to hide the evidence from the advancing Red Army