KATAYOUN SHAHANDEH surveys Iran’s cultural heritage and explains what has been damaged and what could be lost

JONATHAN TAYLOR is fascinated by the philosophical problems that permeate the art of life-writing

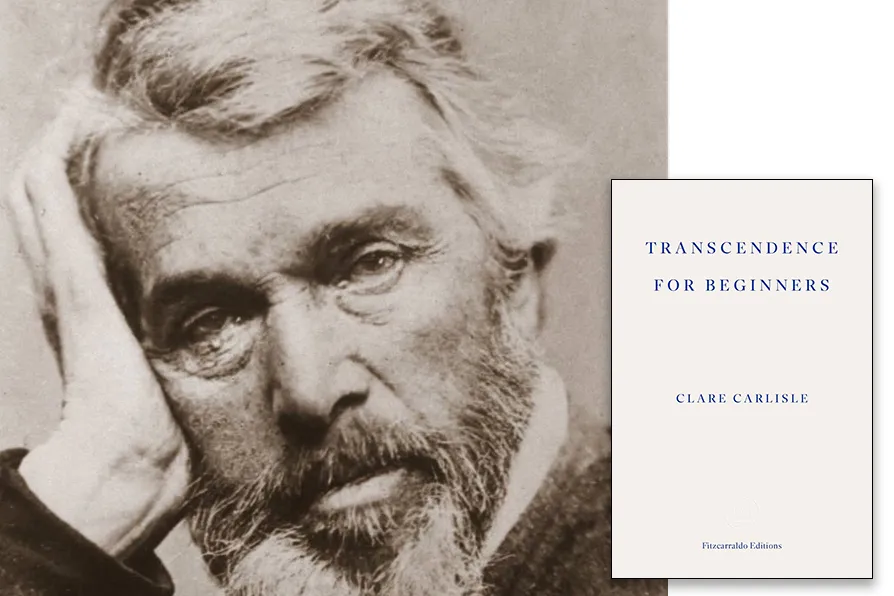

Thomas Carlyle, circa 1860s [Pic: Elliott & Fry/CC]

Thomas Carlyle, circa 1860s [Pic: Elliott & Fry/CC]

Transcendence for Beginners

Clare Carlisle, Fitzcarraldo Editions, £12.99

IN his essay On History (1830), 19th-century historian Thomas Carlyle writes:

“All Narrative is, by its nature, of only one dimension… Narrative is linear, [while] Action is solid. Alas for our ‘chains’… of ‘causes and effects,’ which we so assiduously track through certain hand-breadths of years and square miles, when the whole is a broad, deep Immensity, and each atom is ‘chained’ and complected with all!”

For Carlyle, the historian’s dominant mode of expression – narrative – is incommensurate with their subject matter: a linear, one-dimensional narrative cannot hope to encompass the (near) infinite nature of “real” history.

In her fascinating and beautifully argued new book, Transcendence for Beginners, philosopher Clare Carlisle (no relation to her Victorian near-namesake) tackles a similar problem, in relation to a particular kind of historian: the life-writer, or biographer.

The life-writer is confronted, on the one hand, by the infinite “diffusiveness” of the individual life, and, on the other, the necessity of “drawing a certain line on a page… through space and through time.” “The line of writing is unidirectional,” writes Carlisle. “It only moves forward,” while life itself is full of a million experiences, “innumerable influences,” a constant “flow of faces, atmospheres and tones of voice,” which generally go unrecorded. “No-one… has access to [a] whole life”, so “a work of biography might be begun but in a certain sense can never be concluded” – and ultimately seems “an impossible task.”

Philosophy might be seen as the opposite to life-writing in this regard: rather than devoting itself to the task of encompassing individual subjectivity through narrative, it attempts to view life from above, in more general terms. “Philosophy,” writes Carlisle, “seeks general definitions – what is man? – whereas the biography asks, who is this man? Or, who is this woman?” She goes on to cite critic Adriana Cavarero, who suggests that “unlike philosophy, which… has persisted in capturing the universal in the trap of definition, narration reveals the finite in its fragile uniqueness, and sings its glory.”

Carlisle admits there is something in this opposition between philosophy, on the one hand, and narrative/life-writing, on the other, but then goes on to deconstruct it. After all, philosophy is itself often expressed in the form of narrative, and “properly practised” philosophy and life-writing – according to Carlisle – share a concern with both the general and the individual, the “universal” and the “unique.” A biography, for instance, is at one and same time about a very specific life and implicitly an expression of many or all lives. It can “express itself” and “something beyond itself” because every life is “interconnected [and]… each individual being is at once porous and self-transcending … [One] life expresses a world… ‘Your one little life’ contains untold histories, epic journeys, magnificent hopes, grand passions, immense struggles and profound losses.”

In order to explain the self-transcendent nature of life-writing, Carlisle draws on thinkers as diverse as Spinoza, Leibniz and George Eliot, as well as the powerful image of the “cosmogram” – “an object or a myth or a dance, that offers an image of the cosmos as a whole,” while simultaneously embodying “its specific milieu.” A cosmogram is, at one and the same time, an expression of both the universal and specific, and hence represents Carlisle’s ideal of life-writing: “If we ask how a particular human life expresses a milieu with cosmological dimensions, we are preparing to read it cosmogrammatically. Life-writing then turns out to be a cosmological art.”

As a cosmogram, a biography can ideally encapsulate the “multiple dimensions” of a life and “render… [them] on the page as a line: a slender thread of ink. Yet this line conjures a cosmos.”

This is Carlisle’s answer to the problem posed by the other Carlyle: a linear narrative might well microcosmically encode the whole. Thomas Carlyle, coincidentally, comes to a similar conclusion. In his own essay on biography, he claims that “every mortal has a Problem of Existence set before him [sic], which… must be to a certain extent original, unlike every other; and yet, at the same time, so like every other; like our own,” such that “every man’s Life… is… inclusive of all else.”

Jonathan Taylor is an author, editor, lecturer and critic. His most recent book is A Physical Education: On Bullying, Discipline & Other Lessons (Goldsmiths, 2024).