GUILLERMO THOMAS recommends an important, if dispiriting book about the neo-colonial culture of Uganda under Yoweri Museveni

GORDON PARSONS steps warily in between the lines of Britain’s most famous diarist

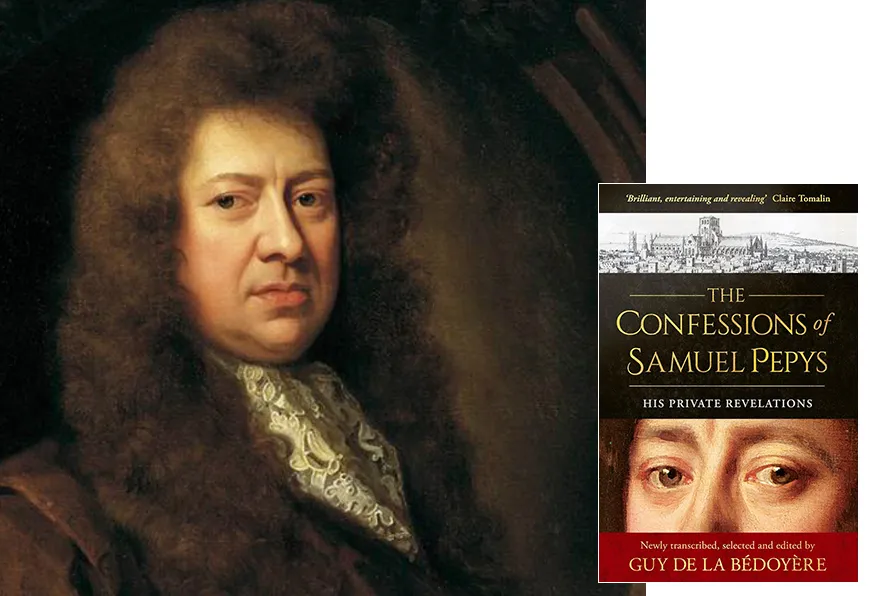

Godfrey Kneller (1646–1723); Samuel Pepys, 1689 [Pic: National Maritime Museum/CC]

Godfrey Kneller (1646–1723); Samuel Pepys, 1689 [Pic: National Maritime Museum/CC]

The Confessions of Samuel Pepys

Guy de la Bedoyere, Abacus Books, £25

AT his death in 1703 one of his many friends described Samuel Pepys as “universally beloved, hospitable, generous, learned in many things, skilled in music, a very great cherisher of learned men, of whom he had the conversation.”

All of his numerous biographers have recognised these qualities in a remarkable man, while having to cope with the darker side hidden in his own polyglot version of the shorthand of his time, that he selectively employed in his million-and-a-half-word diary.

The diary itself is of inestimable value to scholars and historians of the decade which experienced the Plague and the Great Fire of London. Pepys, as a senior civil servant in the Navy Office meticulously recorded his daily experiences, along with a lively picture of social life at the time. For him, however, experiences included a never-ending search for women who could serve his apparently insatiable sexual appetite.

These have been “excused” as amorous escapades or attitudes characteristic of the milieu of the post-Restoration court, where Charles II flaunted his acknowledged mistresses, behaviour which, incidentally, Pepys himself hypocritically condemned.

Bedoyere suggests that what today we would condemn as excessive predatory behaviour was likely to have been a neuropsychological drive, the result of an operation for a bladder stone removal which, given contemporary surgical conditions, he miraculously survived at the age of 25.

Bedoyere has worked assiduously to decode and transcribe Pepys’s polyglot descriptions of his “adventures.” There can be little doubt that Pepys was not alone in his sexual marauding. After all, one of the few Restoration Comedies which may (woke allowing) be staged today, William Wycheley’s The Country Wife, features a leading character, Horner, who spreads the rumour that he is impotent simply in order to have his way with willing ladies.

Just as with our modern sex predators, Pepys used his power to groom and where necessary assault his victims. His regular mistresses were often the wives of some of the shipyard workers whose employment depended on his official position. They would be regularly ready to service him in order to further their husbands’ prospects. In this way, Pepys was free from fearing unwanted pregnancies, which could be passed off onto often willing husbands.

Moreover, although rape was on the statutes as a crime in the 17th century, it was virtually impossible for women to bring a charge, a situation which, for different reasons, might be recognised by many victims today.

Pepys’s targets were always women of an equal or lesser social standing, but he often allowed his imagination to range. On one occasion, noting such an attractive but unavailable lady, he comments on the resulting achievement of being able to masturbate without using his hand.

Only occasionally does he express self-doubts. “But Lord, to see how frail a man I am, subject to my vanities, can hardly forebear, though pressed with ever so much business, my pursuing of pleasure.”

But this “business” could also be quite serious — on one occasion 1668 he addressed Parliament in defence of the Navy office when a corruption charge was brought against it, and delivered a long speech highly praised by the king.

Much of his business consisted in theatregoing. In 1668 he visited the theatre 73 times. May this help to explain why Pepys kept his “secret” diary? There have been many suggestions but, given this delight in theatre, it could be that it gave him the opportunity to relive his “adventures,” observing himself on the great stage of life.

On one occasion, he describes waking in the night after a violent quarrel with his wife, who must have been very suspicious of his outings, to find her poised over him with red hot pincers threatening to put a physical end to those activities.

Certainly, Guy de la Bedoyere’s revelations of the dark side of Pepys, who has been viewed as a lively, amenable character, admittedly with “naughty” sexual propensities, will reveal a much more questionable and complex man than has been hitherto recognised.