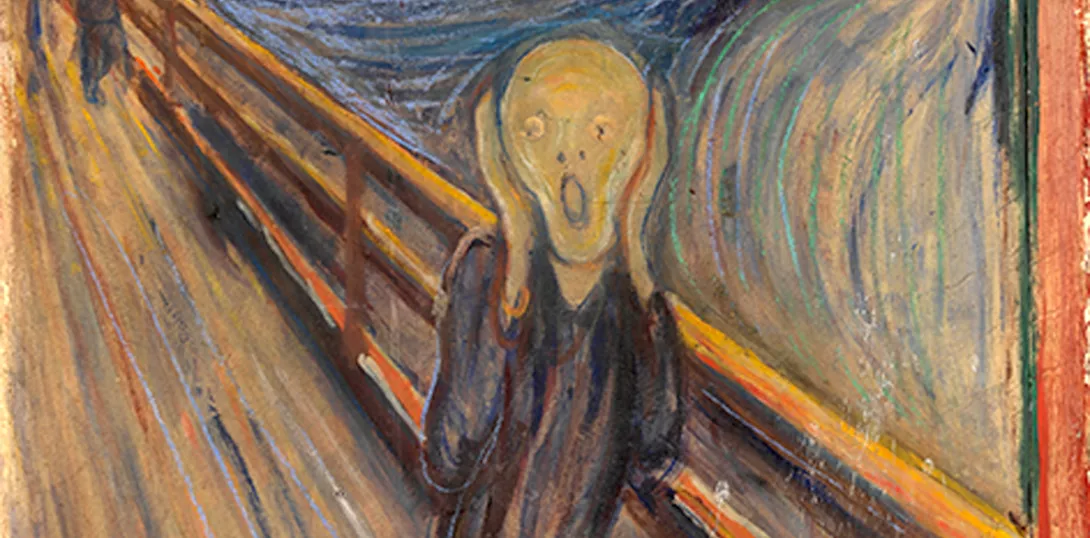

Edvard Munch’s The Scream (1893) speaks to us again today with great intensity.

How did this painting come about? In September 1892, in Kristiana (Oslo), Munch recorded a harrowing experience in his diary:

“One evening I was walking out on a hilly path near Kristiania — with two comrades. It was a time when life had ripped my soul open. The sun was going down — had dipped in flames below the horizon. It was like a flaming sword of blood slicing through the concave of heaven. The sky was like blood — sliced with strips of fire — the hills turned deep blue the fjord — cut in cold blue, yellow, and red colors — the exploding bloody red — on the path and hand railing — my friends turned glaring yellow white — I felt a great scream — and I heard, yes, a great scream — the colors in nature — broke the lines of nature — the lines and colors vibrated with motion — these oscillations of life brought not only my eye into oscillations, it brought also my ears into oscillations — so I actually heard a scream — I painted the picture Scream then.”

Munch’s world-famous painting is based on this experience. His iconic figure hears a searing scream. But why has this painting become so indelibly engraved in the collective memory of the human community? How exactly is the horror captured in the painting?

[[{"fid":"59643","view_mode":"inlineleft","fields":{"format":"inlineleft","field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]":"The Scream, Edvard Munch, 1893 Credit: Public Domain","field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]":false},"link_text":null,"type":"media","field_deltas":{"2":{"format":"inlineleft","field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]":"The Scream, Edvard Munch, 1893 Credit: Public Domain","field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]":false}},"attributes":{"alt":"The Scream, Edvard Munch, 1893 Credit: Public Domain","class":"media-element file-inlineleft","data-delta":"2"}}]]

It is unclear whether the figure only hears the scream or is also screaming in despair, but this seems likely. The hands cover the ears to protect them from the scream, but this gesture also manifests his own horror. As the artist states, this scream originates in nature; it is therefore something profoundly elemental.

In his diary, Edvard Munch records a personal experience that deeply disturbed him and the painting has appealed to viewers on this private level also ever since. However, from our historical vantage point, a further dimension emerges that Munch and his contemporaries certainly did not realise and could only guess at.

The Scream was created at the onset of the imperialist era, with its accompanying profound social and political upheavals.

In the late 19th century, a new, more international, more aggressive stage of capitalism emerged. The world was being redivided, with rapidly growing technological progress and simultaneously increasing urban impoverishment. These developments, with seeming inevitability, lead to the first world war.

Munch lived in Berlin between 1892 and 1894. It is conceivable that his stay in this metropolis not long after the formation of the Reich under Bismarck, when German imperialism was also rapidly gaining strength, intensified the painter’s perception of a disquieting time.

Everything seemed to be spiralling out of control. Nihilism, which also affected Munch, gained new fertile ground with its anti-humanist idea of the meaninglessness of life. It suited the ruling class of the era that the world no longer seemed comprehensible.

Munch experienced the emergence of this new, imperialist stage of capitalism as a young adult.

In 1916 Lenin defined imperialism as follows:

“Imperialism is capitalism at that stage of development at which the dominance of monopolies and finance capital is established; in which the export of capital has acquired pronounced importance; in which the division of the world among the international trusts has begun, in which the division of all territories of the globe among the biggest capitalist powers has been completed.”

According to Lenin, imperialism emerged as a specific phase of capitalism between 1873 (not yet established) and 1900 (established):

“After the crisis of 1873, a lengthy period of development of cartels; but they are still the exception. They are not yet durable. They are still a transitory phenomenon. The boom at the end of the 19th century and the crisis of 1900-03. Cartels become one of the foundations of the whole of economic life. Capitalism has been transformed into imperialism.”

Based on these corner dates, it can be assumed that Munch’s world-famous painting from 1893 artistically captures this transition to imperialism. This is not to claim that the painter himself was aware of such a thing, but rather that Munch’s great sensitivity achieved what Shakespeare expected of true art: “to show ... the very age and body of the time his form and pressure.”

Naturally, personal sensibilities inform a work of art, but its paramount importance lies in the fact that Munch — by facing his own fears — was able to express this scream of the tortured creature as a defining moment of the age in such a way that people all over the world are still moved today.

So while the subject matter of the painting depicts exactly what most establishment art critics describe, namely: a person standing on a bridge near Oslo and hearing a scream that affects him existentially (and shrieking himself), the time of the painting’s creation contributes decisively to its significance.

The scream, as an essential part of the subject therefore shapes the colours, the composition, the structure, the tensions, which heighten it and move it towards horror and despair.

In the form of his painting, Munch breaks away from impressionism and describes a world torn apart, from the perspective of personal perception. Art enters the age of imperialism.

The artist created four further versions of the painting, as well as a lithograph. Since its creation 130 years ago, Munch’s picture, like the Mona Lisa or Guernica, has been engraved in the visual memory of humankind. Munch’s painting vividly evokes in us an empathy that defines our humanity, which we feel when we hear about natural disasters and personal tragedies, but above all about the immense suffering and terror of martyred people in war zones.

Munch’s desperate, screaming face is captured three times in Picasso’s Guernica (1937) - in the mother with the dead baby, the person in flames, the tortured horse, scenes that continue to be caused by imperialist violence and wars today.

Munch gave artistic expression to this horror.