The Star's critic MARIA DUARTE recommends an impressive impersonation of Bob Dylan

Quo vadis?

Finding or refinding its purpose will be fundamental to the future of the Party - what that cannot mean is being a lighter shade of blue, writes PAUL DONOVAN

A Century of Labour

by Jon Cruddas

Polity £25

LABOUR MP Jon Cruddas has produced a timely account of the 100-year history of the Labour Party.

The retiring MP for Dagenham and Rainham poses a number of challenging questions throughout, not the least being does the party have a purpose?

More from this author

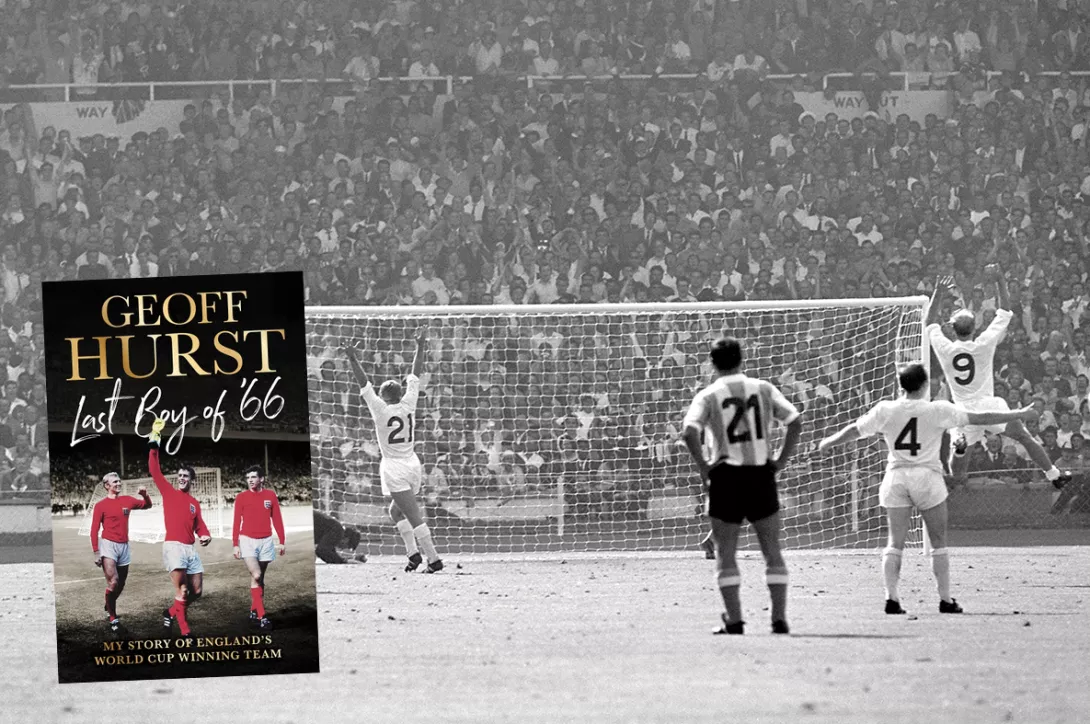

Football fans will enjoy this book from West Ham legend and World Cup winner Geoff Hurst, writes Paul Donovan

West Ham were lucky to lose by only five against league leaders Liverpool, as they served up another lacklustre display at the London Stadium

Similar stories

Genocide, racism and imperialism are in the Labour Party’s DNA, argues TOM SYKES

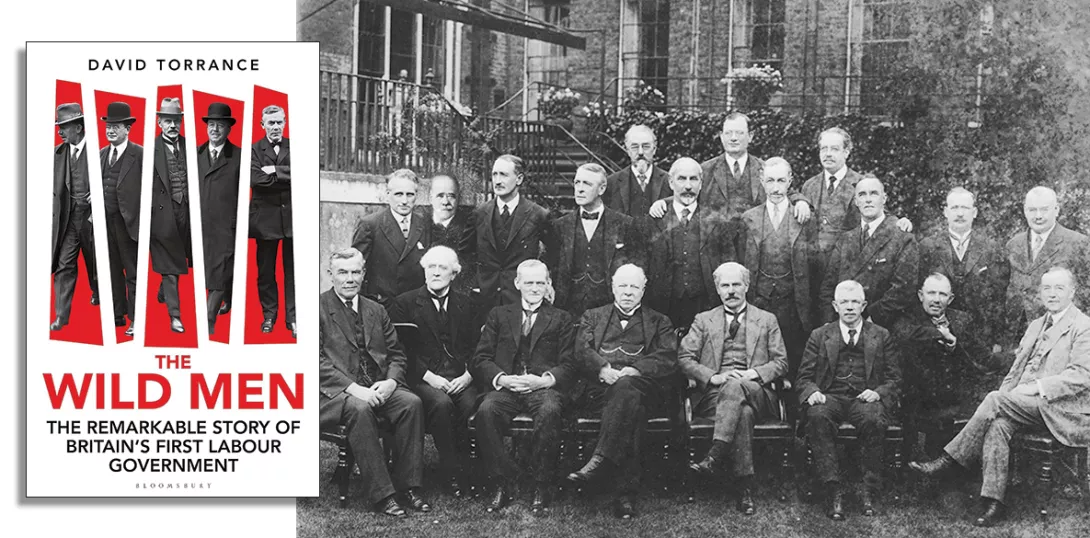

PAUL DONOVAN observes how the first Labour parliamentarians were merely malleable pillars of the establishment

PAUL DONOVAN salutes a timely dramatisation of Aneurin Bevin's life, and the political struggle on the left to create the NHS