SCOTT ALSWORTH suggests that video games have a lot to learn the rich tradition of Marxist theatre

[The National Archives (United Kingdom)/Public domain]

[The National Archives (United Kingdom)/Public domain]

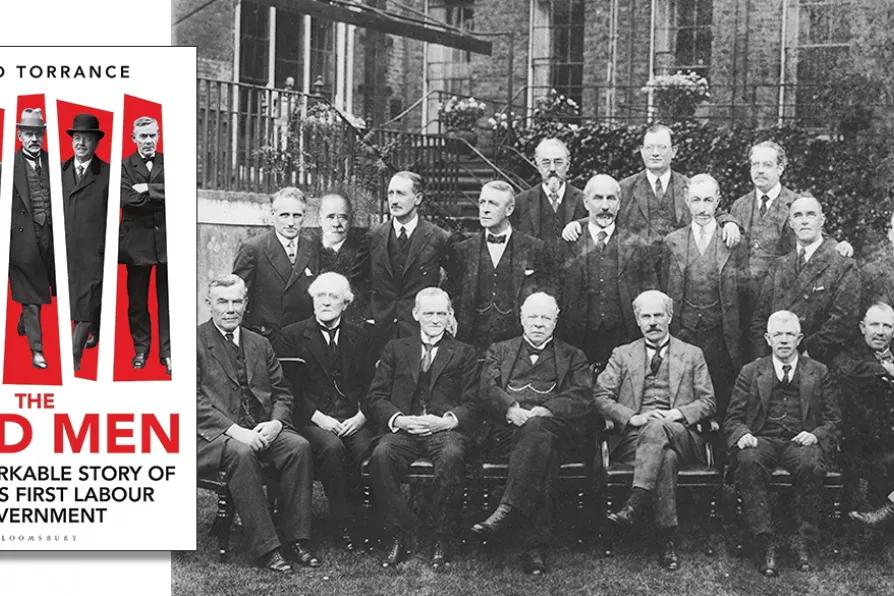

The Wild Men

David Torrance

Bloomsbury, £20

THE main achievement of the first Labour government of 1924 proved to be demonstrating that they were not “wild men” at all.

The Establishment clearly saw the mixture of working-class representatives, elected in 1923, as a potential revolutionary threat to its existence. The British version of the Bolsheviks in Russia. What David Torrance clearly demonstrates is that they were anything but.

There were the initial niceties of dress, certain suits for different occasions. The prime minister had personally to fund the furnishing of Downing Street. The lack of trust of the first Labour administration is amusingly illustrated with the story of four splendid silver candlesticks, which reappeared in the Colonial Office, as Labour minister Jimmy Thomas left.

MARJORIE MAYO welcomes an account of family life after Oscar Wilde, a cathartic exercise, written by his grandson

Building is the solution for much of our housing crisis – and will also help to address poverty, ill health, and even anti-social behaviour and alienation, writes KENNY MacASKILL

STEPHEN ARNELL examines whether Starmer is a canny strategist playing a longer game or heading for MacDonald’s Great Betrayal, tracing parallels between today’s rightward drift and the 1931 crisis

SOLOMON HUGHES details how the firm has quickly moved on to buttering-up Labour MPs after the fall of the Tories so it can continue to ‘win both ways’ collecting public and private cash by undermining the NHS