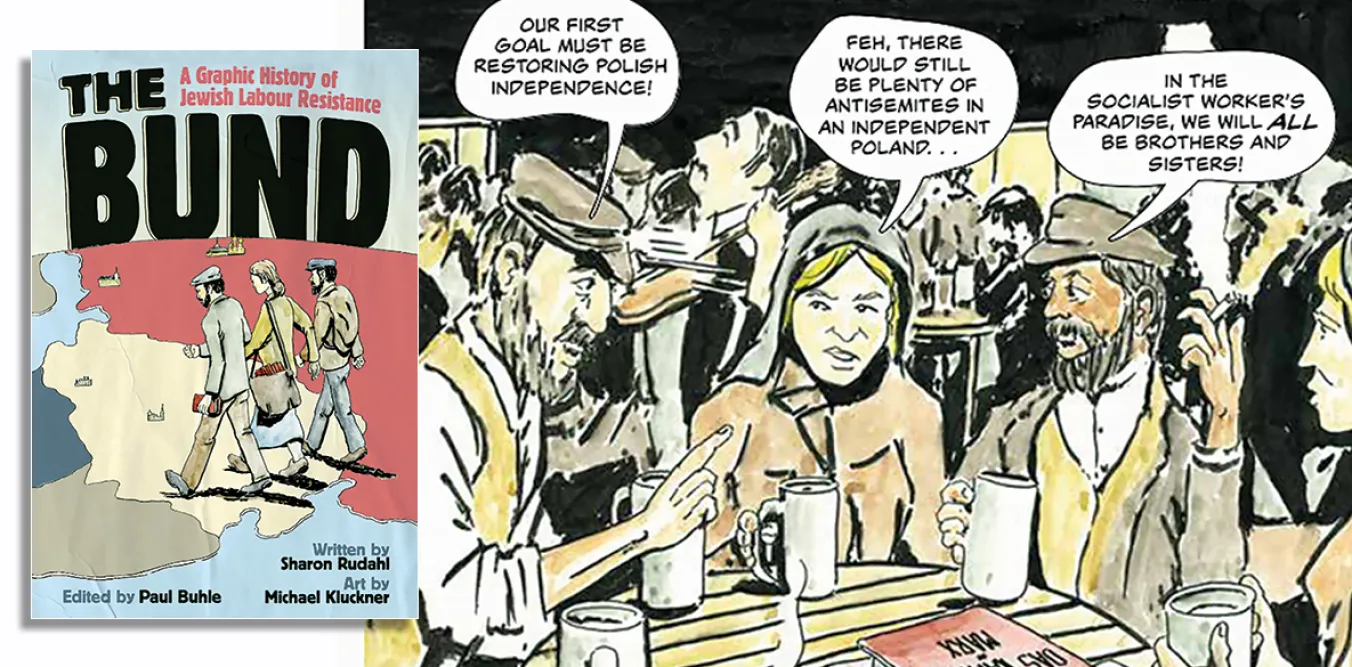

The Bund

Sharon Rudahl and Michael Kluckner

Between the Lines, £22.50

THE late Scottish Marxist Neil Davidson described the political division in Jewish Europe as one between two different responses to the brutality of anti-semitism.

One was to see that the oppression and persecution of Jews necessitated a new society in a Jewish majority state: this was zionism and ended in the catastrophe we see today. The other response was to view the oppression and persecution of Jews as inherent and brutal aspects of capitalist oppression that necessitated a new society for everyone: a society free from capitalism, and from the state. This was socialism, communism, Bundism, and its many lives and legacies continue to exist today, though they are often erased or suppressed.

One such legacy is the beautiful new graphic novel The Bund by Sharon Rudahl and Michael Kluckner.